by Sandra Gulland | May 17, 2019 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Mistress of the Sun, Resources for Writers, The Josephine B. Trilogy, The Writing Process, Work in Process (WIP) |

In Canada, I have a tall narrow bookcase of books—one of many I have in our house. This one includes poetry, novels I’m either reading or would like to read, and an embarrassing number of books on writing. I am a collector, apparently, a collector of books on writing.

This morning, as I was drinking my delicious mug of decaf, I took three black binders down from the top shelf. I was curious: what were they?

One was a collection of printouts of writing exercises by the New York agent Donald Maass. Another, a thick, heavy binder, was labelled Truby. In it were printouts from master story guru John Truby. I have a lot of Truby—including a series of tapes and his book The Anatomy of Story (which overwhelms me at the first chapter every time I open it). I recalled that at one time Truby offered interactive story analysis on his website; I think it was free, an amazing offering. All the printouts were from his website.

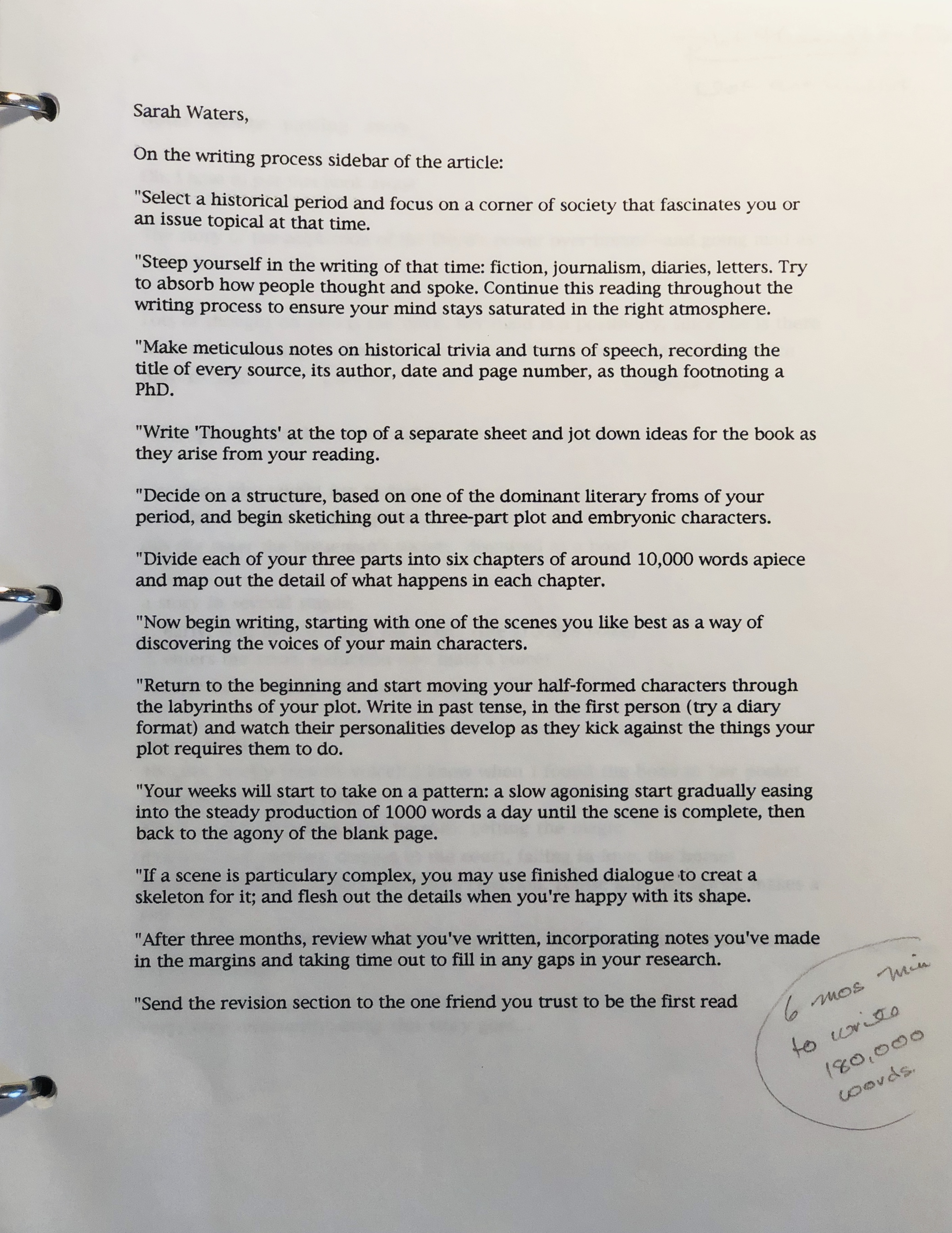

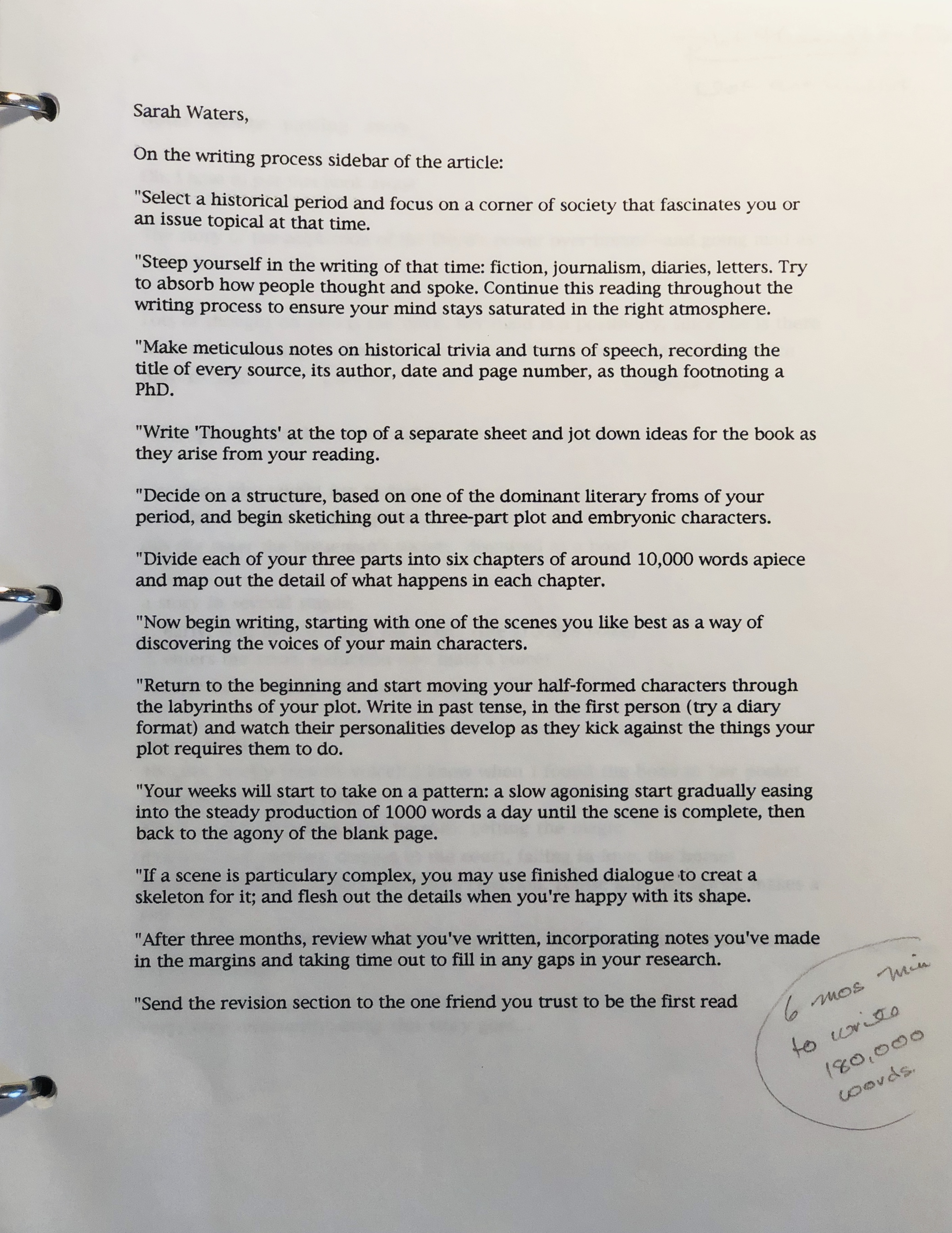

The third binder, labelled Story Tools, was of a middling size. The first page was a list of Sarah Waters’ instructions on how to write a historical novel. Her wise words are no longer online—at least not that I can find—so here it is, my gift to you. (Click here to see the full pdf.)

In the corner I had written: 6 mos min to write 180,000 words.

I wondered when I had written that note. The second page in the binder gave a clue.

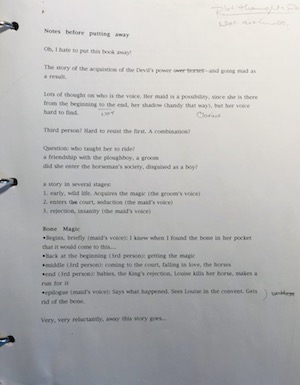

Notes before putting away.

I must have written this after I’d been offered a contract to write the Josephine B. Trilogy. Several months before I had finally completed an acceptable draft of The Many Lives & Secret Sorrows of Josephine B., the first novel in the Trilogy. While my agent was looking for a publisher, I had started work on what was to become, nearly two decades later, Mistress of the Sun. On signing a contract for a trilogy, I reluctantly put the project away.

So: all this was Very Long Ago, as I was setting out on this 32-years-and-counting writing adventure.

Sarah Waters’ advice on how to write a historical novel is a treasure. I’ll be returning to it.

The photo at top is of Sarah Waters, 2010, by Sam Jones, as seen in the article in the Guardian on Sarah Waters’ 10 rules for writers (rules which are, of course, spot on).

by Sandra Gulland | Nov 22, 2018 | Adventures of a Writing Life, My Life, Recommended Books, Movies, Podcasts, etc., The Josephine B. Trilogy |

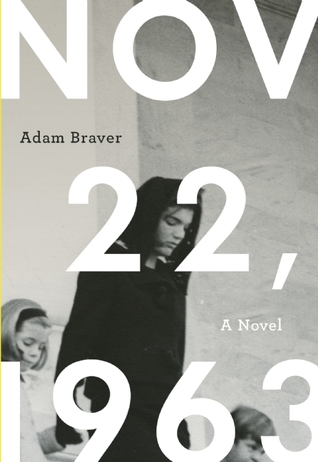

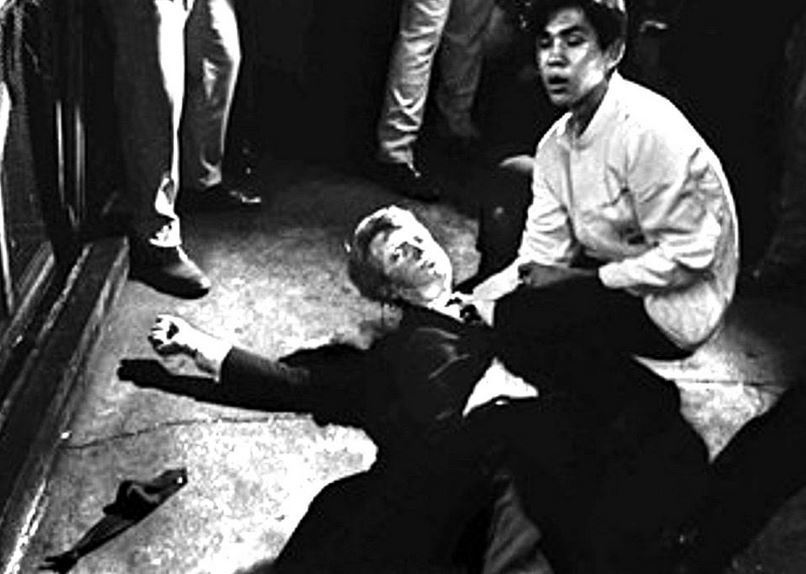

JFK was murdered on November 22, 1963, fifty-five years ago today. I was nineteen and in university. I don’t remember the moment I learned — How is that possible? — but the images and the shock of it are indelible in my memory.

I have since read a moving biographical historical novel, titled, simply, Nov 22, 1963, by Adam Braver.

The assassination was made all the more horrifying in learning in this novel that JFK and Jackie had recently suffered the death of a baby. This tragic trip to Texas with her husband was Jackie’s brave first public event.

A Berkeley childhood

I grew up in Berkeley, California. Air raid siren drills were common; there was always the fear of annihilation. At Girl Scout camp, I remember a cloudy day being attributed to the test of a nuclear bomb in near-by Nevada. I was assigned to write stories about our last day alive in Grade School.

My high school years in Berkeley were vivid with protest. I was a proud member of Students for a Democratic Society. In English, I sat next to Tracy Simms, who led the very first sit-in against a hotel in San Francisco that did not hire Blacks.

These were intense years, rich with both excitement and fear. The Whole Earth Catalogue was Google in print. It’s message was: “You can do anything, go anywhere. Here are the tools.” It was a powerful concept, and an entire generation took it to heart.

Although I don’t remember the moment I learned of Kennedy’s assassination, I remember, vividly, the night of the Bay of Pigs on April 17, 1961, two-a-half years before. I was seventeen, living in San Francisco with roommates in the Castro district, going to San Francisco State. We believed that it could be the end of the world, our last night alive. (In fact, recent scholarship shows how very close it came to being just that, by an accident of communication.) I imagine that there was a surge in births nine months later, for many young couples succumbed. Why wait?

The three assassinations

On April 4, 1968, four-and-a-half years after Kennedy was killed, Martin Luther King was assassinated. I was twenty-one, married and working in a factory in Belmont, California — a factory that provided micro-chips for fighter jets. I had to sign a Loyalty Oath to work there. I remember the Ohio Flute Society (or something similar) being listed as one of the suspicious organizations.

I couldn’t sleep the night of April 4. I got up and went downstairs. It was very late. I turned on the TV: screams, a newscaster’s urgent voice, flickering images. King had been shot.

The next morning, at the factory, a white guy riding a trolley yelled, fist raised, “We got another one!”

And then, only two months later, on June 6, the same thing. I couldn’t sleep, I went downstairs and turned on the TV. A newscaster’s urgent voice, flickering images, screams. Bobby Kennedy had been shot.

I’d been canvassing for him, handing out leaflets — it was my first involvement in a political campaign. Belmont was a conservative town, yet the day after Bobby Kennedy’s death there was, I was told, a rash of suicides.

A decision

That morning, the morning after, my then husband and I went to Half Moon Bay. Sitting on a sand dune overlooking the Pacific, stunned by the news, I said I wanted to move. Away. To another country. Bobby Kennedy’s death was the straw that broke my back.

And thus the decision was made to leave my country of birth for a more peaceful realm. Move to Canada — a “healing” country in the words of the wonderful Carol Shields, who had herself immigrated to Canada from the US. I found it to be just that.

A Canadian citizen now, I have never regretted that move. Even so, a part of me will always be American. A part of me will always love that country — love it, and fear for it. Which is one reason I, like so many others, am addicted to the horrifying daily news.

Are things worse now than they were during those violent and tumultuous years? I would say yes, although in a more institutional way. I believe in democracy, and greatly fear for it.

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 27, 2018 | Baroque Explorations, The Game of Hope, The Josephine B. Trilogy |

A master of the sound bite, Napoleon would have been in his element in this Age of Twitter. Here is a sampling of some pithy Napoleon quotes, some of which his stepdaughter Hortense views ironically in The Game of Hope.

“What a novel my life has been!”

“Great ambition is the passion of a great character. Those endowed with it may perform very good or very bad acts. All depends on the principles which direct them.”

“If you wish to be a success in the world, promise everything, deliver nothing.”

“All celebrated people lose dignity on a close view.”

“Courage is like love; it must have hope for nourishment.”

“Victory belongs to the most persevering.”

“History is the lies we all agree upon.”

“What then is, generally speaking, the truth of history? A fable agreed upon.”

“A throne is only a bench covered in velvet.”

“Our hour is marked, and no one can claim a moment of life beyond what fate has predestined.”

“A leader is a dealer in hope.”

“Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.”

What are some of your favorites? SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Dec 2, 2015 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Game of Hope, The Josephine B. Trilogy |

Tracking down facts can be a time-crunching task … but a very enjoyable one when the goal is in sight.

I began with a simple question: Where was Hortense’s father executed and buried? I think these were things she might have wanted to know.

Portrait of Josephine and her two children, Hortense and Eugène, visiting their father in prison.

False leads

In the process, I found many wrong answers … which reinforces the common knowledge that the Net can’t be trusted. However, I knew enough to know when the answer was wrong, and kept looking.

In the process I ended up making a correction to a Wikipedia page … which rather thrilled me. Alexandre was defined, simply, as the lover of Princess Amalie of Salm-Kyrburg, a friend of Josephine’s who secretly acquired the land after the Revolution because her brother is buried there. Not only was it curious that Josephine and their children were not mentioned, but I very much doubt that Alexandre was Amalie’s lover. Other women, certainly, but not Amalie.

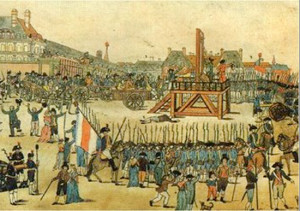

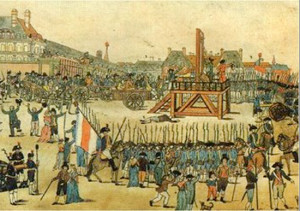

Place du Trône-Renversé—now Place de la Nation—where Hortense’s father was guillotined.

Alexandre was guillotined not in the Place de la Révolution (Place de la Concorde now) or Place de Grève (in front of the l’Hôtel-de-Ville), as if often claimed, but in Place du Trône-Renversé (now Place de la Nation), on the western edge of Paris. Apparently the other execution sites had become so bloody they had to find a new spot.

Mass executions at the height of the Terror

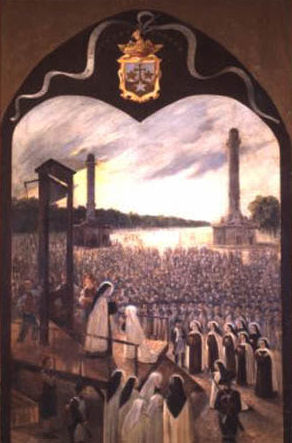

In a matter of about 6 weeks (from June 13 to July 27, 1794) 1306 men and women were guillotined, as many as 55 people a day. I imagine that it was hard work keeping the blade sufficiently sharp.

How to dispose of all the bodies?

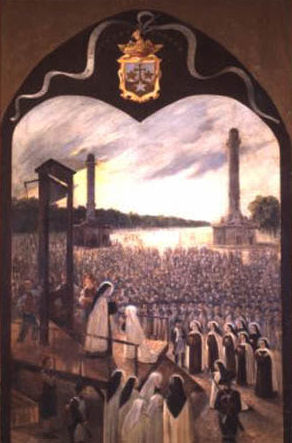

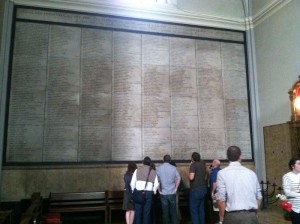

It was also hard work disposing of the bodies. What is now the Picpus Cemetery was then land seized from a convent during the Revolution, conveniently close to Place du Trône-Renversé. A pit was dug at the end of the garden, and when that filled up, a second was dug. The bodies of all 1306 of the men and women executed in Place du Trône-Renversé were thrown into the common pits including 108 nobles, 136 monastics, and 579 commoners … .

The mass graves are simply marked.

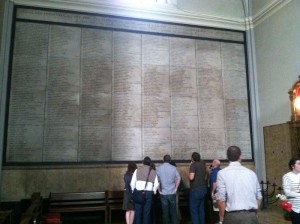

One of two wall listing the names and ages of the dead.

Le Cimetière de Picpus today.

Of those executed, 197 were women, including 16 Carmelite nuns, who went to the scaffold singing hymns.

In all the research I’ve done in Paris over the decades, I’ve yet to go to either the Place du Trône-Renversé (Place de la Nation) or the Picpus Cemetery. I believe I’m due.

by Sandra Gulland | Nov 30, 2015 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Resources for Book Clubs, The Josephine B. Trilogy |

The above image is a portrait of Josephine before she met Napoleon.

It is always hard for me to read biographies about Josephine. I’ve yet to read one I don’t have a quibble with. The same holds for a “Great Lives” BBC broadcast I listened to recently on Josephine. It pleases me that Josephine was chosen as one of the “Great Lives,” but there were a number of statements made that I very much question. One statement made was that she was very promiscuous. I ask you: How many lovers does a “very” promiscuous woman have?

How many lovers did Josephine have?

For Josephine, there was General Hoche, and—as is claimed — Director Barras, and — also claimed — Captain Charles.

Portrait of General Hoche.

Although there is no absolute evidence regarding Josephine’s involvement with General Hoche, I personally believe that he might have been her lover. We really know nothing concrete, but Hoche was a lovable, attractive man, and she could very well have loved him.

Director Paul Barras

Regarding Director Barras, the question posed on the broadcast was, “What did she have to offer him?” The question was rhetorical: I.e. nothing, it was implied.

Au contraire. My historical consultant, Dr. Catinat, an authority on Josephine, told me that what Josephine had to offer were connections to wealthy Caribbean bankers, contacts she had made as a Freemason. (Women could be Freemasons then.) Barras, although powerful, was very much in need of financial aid, and Josephine was able to put him in contact with men who could help.

Josephine received money from Barras, no doubt, but Dr. Catinat felt that in balance, Barras was the one who came out ahead. This perspective is never mentioned. Instead, it is assumed that because Josephine was receiving money from Barras, she had to be sleeping with him.

A UK political cartoon showing Josephine and her friend Therese dancing naked for Director Barras, Napoleon looking on.

Several mentions were made of the cartoon of Josephine and her friend Therese dancing naked for Barras, as if this was something that actually happened. They failed to note that the cartoonist was from the UK, which was at war with France. Enemies delight in portraying the enemy in a vile light. Again, while writing the Trilogy, I checked with my knowledgeable French consultants, who declared such stories untrue.

Was Director Barras heterosexual?

Dr. Catinat also told me that Barras was homosexual, possibly bisexual. He had no progeny — in spite of claims that he had many female lovers. I am personally inclined to think that he was more homosexual than bisexual, but there really is very little to go on.

Long ago someone told me that, in her opinion, Josephine was a woman who enjoyed the company of Gay men. Frankly, that rings true to me. Josephine was bohemian, and she loved men and women of the theatre and the arts.

And what about Captain Charles?

Which leads us to Josephine’s third so-called lover: Captain Charles.

Sweet Captain Charles, Josephine’s business partner.

Hippolyte Charles, too, had no progeny — that we know of — and although we know next to nothing about his personal life, in manner he was gay as a tea party. Supremely fashionable, he enjoyed dressing as a woman.

Furthermore, at the time when Josephine was supposedly having a torrid affair with the Captain, she was quite ill, suffering from fevers and violent headaches, likely brought on by a premature menopause (the result of her imprisonment during the Revolution).

The portrait of Josephine as a woman having a torrid love affair at this time is hard to fathom. I don’t know about you, but I simply cannot see Josephine in the bed of either of Director Barras or Captain Charles. And even if I could, would these three lovers make her worthy of the label “very promiscuous”? I think not.

The BBC broadcast mentioned that Josephine was mesmerizing to men. Yes, she certainly was. What they failed to mention is that she was well-beloved by women as well. As a rule of thumb — at least in my book of Observations of the Human Species — is that a promiscuous, manipulative, calculating woman is given a wide berth by other women. Josephine was trusted by women.

I rest my case.

(For more on this theme, see Josephine: Saint or Sinner? (Who knows?)

What have I been doing?

Other than spending quite a bit of time in Physio Therapy to help my Hip Bursitis (ouch!), I continue to wrestle with the Moonsick outline. It’s a big job, but I’m happy to report that it is coming along.

Great links to share…

The news continues to be dire. I am given hope by the resilience and creative joie d’vivre of the Belgians in their response to the order not to post telling photos to social media during the lock-down. National emergency? Belgians respond to terror raids with cats. This one is one of my favourites:

This YouTube video of people dancing on a Paris Metro is pure joy to watch.

I belong to a FaceBook group of authors, and now and then one of the members asks for help with coming up with a title. One of the authors posted a link to a Title Generator. It may never come up with a usable title, but it’s fun.

I started writing historical fiction because I wanted to imagine a world “peopled” by horses. I no longer have a horse of my own, and my riding days are behind me, but I continue to be captured by these beautiful creatures. This video on wild horses is stunning.

Have a great week!

by Sandra Gulland | Oct 5, 2012 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Josephine B. Trilogy |

[From a portrait of Josephine, painted by Appiani during her first voyage to Italy.]

I’ve had very interesting comments on this blog from a reader in Russia, concerning Josephine. “La Reine Margot” raises a number of questions, which I’m going to attempt to answer here. (Please keep in mind that it has been over a decade since I was deep into research into Josephine’s world! There might well be new findings. Consider this an evolving discussion.)

Basically, La Reine Margot would like to know about the relationship between Josephine and Hypolite Charles. “I know that you have some doubts about a sexual relationship between Josephine and Charles.” She’d like to know why I have doubts.

First of all: lack of real evidence. There is only gossip. La Reine notes the saying, “Where there is smoke there is fire.” True, but one learns when studying history that gossip is often used as a weapon, often intentionally. (As when the English planted the rumour that Josephine’s daughter Hortense was pregnant by her step-father Napoleon.) Smoke clouds are sent up, if you will, to make people suspect a fire. One learns, too, that the partners of powerful men are often maligned—something one sees often now, as well.

“Of course the Josephine’s letters to Charles are fakes … but what is the story of this fake? … What is the reason for this hoax?”

It’s impossible to know who created this hoax, but it’s easy enough to see who financially profited from it: the biographer/historian who first printed it.

And from what sources come this affirmation? If I remember correctly there are two main sources: the dutchess d’Abrantes memoirs and those of monsieur Hamelin. Laura [d’Abrantes] and her co-author Balzac of course retold gossips. But were these gossips unfounded?

In short: I think yes.

Abrantes was mean in her memoirs with respect to Josephine, but keep in mind that they were published after Napoleon had been exiled, when she had a lot to gain by this stance. (Correct me if I’m wrong.) It’s worthwhile noting that in Abrantes’ letters to friends written while Josephine was alive, she was nothing short of worshipful in her descriptions of the Empress—a strikingly different point-of-view from that stated in her memoirs.

As for Hamelin’s memoirs… If he lied, what was the reason? Perhaps he invented some details. but what was his purpose to lie about the very nature of the relationship of Josephine and Charles?

Why would Hamelin lie? He was a notorious lier, for one thing. (For another: when was his memoir published? I tried, without success, to find out—but that might provide a clue.)

All Hamelin said was that he saw Charles’s coat outside Josephine’s room—and from that one thing, all is conjectured. Even if true, I think Charles and Josephine might well have had reason to be behind closed doors: counting the profits from their illicit financial endeavours and plotting future investments most likely (IMO). Remember: this was an ill woman going through a violent and early menopause. It’s not impossible that she was having an affair with Charles, but it’s not impossible that she was not.

Are there any others sources? if I remember correctly Bourrienne described that it was Junot who finally told the truth to Napoleon. I never understand the reason for what he decided to do it but I can’t understand his reason to lie too. Louise Compoint of course had this reason. But he?

What did Junot have against Josephine? Josephine fired her femme de chambre Louise Compoint for sleeping with him, for one thing. Louise did her best to malign Josephine after, and I wouldn’t be surprised that she recruited her lover into this effort. (Ironically, Louise, later in need of money, came to the then Empress Josephine, who, never one to hold a grudge, gave it to her.)

Josephine had a number of male friends, but most notably Barras and Charles. She was a modern woman in this respect: comfortable in the world of men. Someone once said to me a long, long time ago: “She enjoyed the company of homosexuals.” All this is conjecture, but I sense this might have been true. Before she became Empress, Josephine was a bohemian woman with artistic tastes.

And the nature of the relationship Josephine and Barras? They certainly were friends and partners. But were they lovers? As for me, I think that they were. I suppose that this man was bisexual, but not gay. If he was gay, who was the father of one of the children of Therese Tallien?

Therese only had one child—a daughter, Thermidor—and Tallien was the father. I don’t believe I’ve ever read that she had a child by Barras. (Again, let me know if I’m mistaken.) To my knowledge, Barras did not have any children.

This child if I remember correctly was born in the chateau Grosbois and it was common knowelege that it was his child. And personally I can’t believe that this canny and licentious man could help Rose without demanding sexual toll in return.

I’d be interested to know your source!

Barras was “repaid” for his help to Josephine many times over by the powerful financial contacts Josephine was able to provide to wealthy Island bankers she’d come to know as a Freemason. Dr Catinat told me that in the exchange of goods and favours between Josephine and Barras, Barras was very much the winner. There was no call for a “sexual toll” in return. The claim that Barras must have been enjoying Josephine’s sexual favours is based on the assumption, in part, that that is all a woman has to offer.

When did Josephine’s [menstrual cycle] stop? What was her age?

You can understand that this type of information is not revealed! We can only guess. What we do know is that Josephine said she was pregnant by Napoleon while he was in Italy. It’s later conjectured that she was lying in order not to have to join Napoleon in Italy. And then, again, it’s conjectured that she was lying when she wrote to Napoleon to say she was very sick.

But imagine that she was not lying: what if her menstrual cycle had stopped and she assumed it was because she was pregnant? If you look at the evidence—various letters, etc.—it’s clear that she really was quite sick during this period of time. Dr Catinat, who is a medical doctor (as well as a foremost expert on her life), suspects that she’d gone into early menopause at the age of only 32. Frankly: this fits. It would explain why she thought she was pregnant (missed period), and why she was so prone to tears at this time.

On top of that, clearly she had something amiss, for she suffered fevers. Quite possibly she had some sort of infection. All this is during that famous trip to Italy with Charles and Junot and Hamelin. I find it hard to imagine a torrid love-affair with Charles while in such a state, and in such company.

As for Charles: he married quite late and never, to my knowledge, had children. No doubt he and Josephine were close … and no doubt they were in secretly involved financially. It’s possible that there was a sexual relationship … but it’s also possible that there wasn’t.

When I was in Paris last summer for the filming of the documentary about Josephine, I chatted at length with Bernard Chevalier, former curator of Malmaison and co-author of a biography about Josephine. I asked him: “If you could ask Josephine one question, what would it be?”

He said, “I would ask her about Captain Charles.”

And I said, “Me, too.”

Because, frankly, we really don’t know.