by Sandra Gulland | Dec 3, 2011 | Adventures of a Writing Life, The Shadow Queen, The Writing Process |

My editor, Iris Tupholme at HarperCollins Canada, likes my 5th draft of This Bright Darkness (working title) “very much.”

You can imagine how relieved and happy I feel.

This time, when I submitted the manuscript, I included a description — the type of thing a reader might read on the cover flap. It’s a draft, and too long, but here it is:

This Bright Darkness

When a maid’s duties include a lot more than making up the bed . . .

This Bright Darkness is a work of fiction inspired by the real life of a maid: Claude des Oeillets. The daughter of itinerant actors and therefore impoverished and socially scorned, she nevertheless rises to become the confidential attendant to the most powerful woman in the 17th century French court of the Sun King: Madame de Montespan, mistress of the charismatic king. However, in Claude’s so-called “respectable” position, she is required to obtain love potions and other magical charms as well as occasionally satisfy the king’s sexual needs (thereby bearing him a daughter).

Claude’s life is like an ever-revolving stage set: in the First Act, she’s the starving child of a family of caravan players, devoted to tending her beloved “half-wit” baby brother; in the Second, she’s with the greats of French theatre — Pierre Corneille, Molière, Racine — witnessing her mother’s amazing rise to stardom in the fantastical (but cut-throat) world of the 17th century French stage; in the Third, she’s front and center in the dazzling world of the charismatic Sun King.

Insinuating herself throughout the worlds of both the theatre and Court is the witch Catherine Voisin, sometimes benevolent and kind, but ultimately ruthless, a woman willing to sacrifice innocent lives in order to satisfy the corrupt desires of her wealthy clients. A woman who ultimately pays for her sins on the pyre — but not without exposing the rot at the heart of these glittering worlds.

Claude rises from poverty to a position of power and influence because she is loyal and can be trusted, a vow she made as a teen to her father — but as the mercurial Montespan becomes ever more desperate to hold onto the King’s sexual favor, innocent love charms move into the realm of deadly Black Magic, and Claude must choose between betraying a trust or doing the right thing — an act which will put her own life at risk, as well as the lives of those she loves dearest.

What do you think? Edits welcome!

by Sandra Gulland | May 1, 2011 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Shadow Queen |

The main character of the novel I’m writing now is relatively unknown. She was the daughter of a theatrical star and a maid to Madame de Montespan, the Sun King’s mistress (the woman we all love to hate).

As part of her duties, she was required to have sex with the King when Montespan was out of sorts.

This is not one of the duties mentioned in The compleat servant-maid, a 17th century book by Hannah Woolley on the work of maids, and dedicated to “all young maidens.”

I just obtained this invaluable guide for maid of all sorts: the Waiting-Gentlewoman, House-keeper, Chamber-Maid, Wet and Dry Nurses, House Maids (in “Great Houses”), Cook-Maids, Scullery-Maids, Laundry-Maids and Dairy-Maids.

Clearly: a lot of maids. “And they all hated me,” claimed my main character Claude, defending herself against accusations of murder and other indecencies.

I adore leafing through guides of this sort; one learns so much:

Do not put any Soap on your Tiffany…

To clean Points and Laces: Take white Bread of half a Day old, and cut it in the middle, and pare the Crust round the Edge, so that you may not damage your Point or Lace when you rube them…

Plus essential recipes for taking away freckles and making teeth white “when very foul or black.”

But nothing about sleeping with your employer’s lover … not one word. Much less what to do when you bear him a child or two. Tant pis.

{Painting: Madame de Montespan in her chateau at Clagny, near Versailles. This post was first aired on Hoydens and Firebrands, a group blog by writers who write novels set in the 17th century.}

by Sandra Gulland | Feb 17, 2009 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Shadow Queen, Work in Process (WIP) |

On reading the book Strange Revelations, I was convinced that Claude des Oeillets, the heroine of the novel I am writing, was guilty of dealing with the witch Madame Voisin.

The testimonies against Claude recorded in the Bastille Archives are overwhelming in number and detail. How could so many people be wrong?

Les Des Oeillets: une grande comédienne, a biography about Claude des Oeillets and her mother

Now, having read and reread Jean Lemoine‘s Les Des Oeillets: une grande comédienne, une maitresse de Louis XIV, I’m not so sure.

Jean Lemoine is one of those wonderfully careful historians who documents every claim. The book is, in fact, made up of documents: leases on houses, money loaned, money paid, last wills and testaments. The stuff of history.

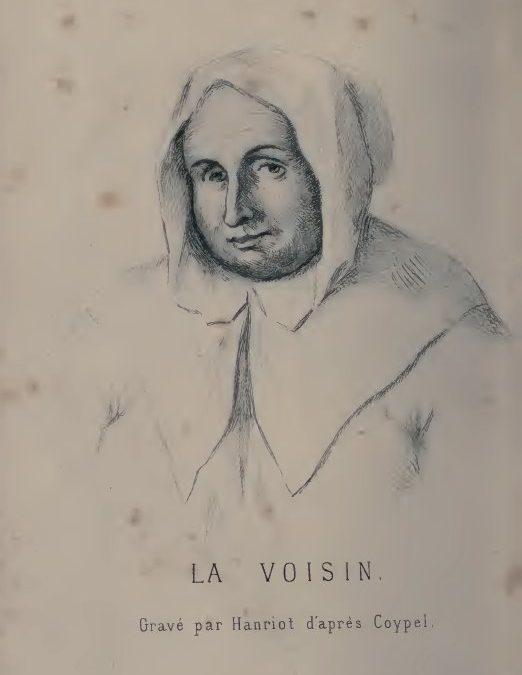

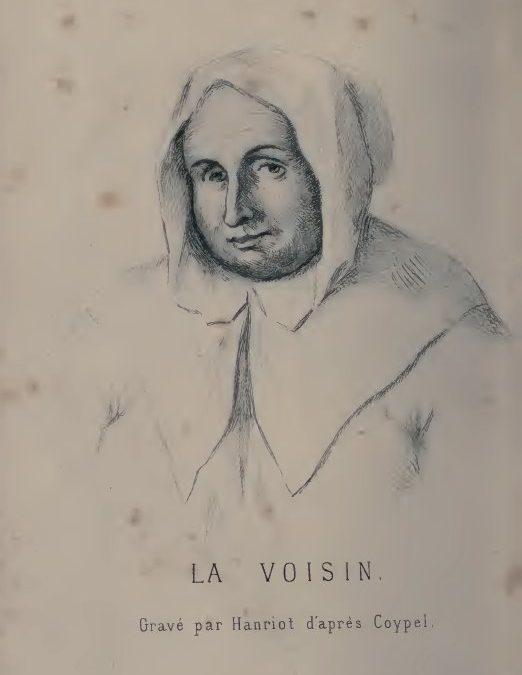

The witch Voisin

What’s telling, to me, is that Madame Voisin insisted, under terrible torture, right up to the day of her execution, that she’d not had any dealings with either Claude des Oeillets or her employer Athénaïs de Montespan.

Voisin had squealed on many, many others at court, most of them high-and-mighty. There was nothing to be gained in not mentioning Claude des Oeillets or Montespan. What would be her motivation?

Possibly: to tell the truth?

The accusations poured in from other prisoners after Voisin’s execution. What I’ve learned from Lemoine’s work is that Claude was called in by Louvois, the Minister of War, and, horrified by what was being said, insisted on being shown to her accusers. She swore on her life that they would not know her.

The “test” was unfortunately mishandled (as noted later by minister Colbert): Claude des Oeillets wasn’t shown to the prisoners with other people. The prisoners had been grilled shortly before about Claude. It was easy enough for them to guess who she was.

She insisted on another meeting with Louvois, pleading her case. This was followed up with a letter, in which she offered explanations. Louvois—who would have been happy to find any evidence compromising Athénaïs de Montespan—was ultimately convinced of her innocence … as was the King and Colbert.

Conclusion: Was Claude des Oeillets guilty?

And so: I’m not yet sure. The reason why Claude’s guilt or innocence is critical is because it directly implicates Athénaïs—the Shadow Queen of France at that time. I’ve ordered Jean Lemoine’s book on Athénaïs and the Affair of the Poisons. Until then, I remain puzzled, unconvinced either way.

Note: this post was written while I was researching and writing The Shadow Queen. If you have read the novel, you will know that I reached the conclusion that Claude (“Claudette”) was both guilty and innocent.

by Sandra Gulland | Jan 23, 2009 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

We arrived back from the beach yesterday afternoon. I’m almost unpacked —although not quite. We returned to piles of magazines, mail (bills), Christmas cards, plus several books I’d ordered before we left. Two of these are on the Affair of the Poisons, which features in The Next Novel. One, Strange Revelations, is a scholarly work, and recently published, so I am eager to read it.

We arrived back from the beach yesterday afternoon. I’m almost unpacked —although not quite. We returned to piles of magazines, mail (bills), Christmas cards, plus several books I’d ordered before we left. Two of these are on the Affair of the Poisons, which features in The Next Novel. One, Strange Revelations, is a scholarly work, and recently published, so I am eager to read it.

Immediately I skimmed the index and skimmed the bits about Claude des Oeillets, the main character of my novel. I was rather disturbed to descover that the author of this book, Lynn Wood Mollenauer, states that Claude “probably” plotted to kill the king.

Well! Strange revelations indeed. This would put a rather different cast on my character and a bomb in my plot. First, I have to be convinced myself.

Nous verrons!

by Sandra Gulland | Dec 7, 2008 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, Recommended Books, Movies, Podcasts, etc., The Shadow Queen |

{Above: The cover of the Sandra Gulland INK edition of The Shadow Queen, in which Madame Voisin is an important character.}

I have been delving into the Affair of the Poisons again, trying to understand the roles of Athénaïs (Madame de Montespan), and her maid Claude des Oeillets in this sordid affair. In sorting it out, I first revisited Anne Somerset‘s The Affair of the Poisons; Murder, Infanticide & Satanism at the Court of Louis XIV, an excellent book, in my opinion, with clear and specific references.

Most of Somerset’s information is from the Bastille Archives (Archives de la Bastille), where one can read the word-by-word interrogations of the hundreds of people arrested for poisoning, witchcraft and infanticide. Through the French on-line library — Gallica — I’ve been able to download all seven volumes, and so have them on my computer. In this way, I’ve been able to check Somerset’s specific references by going to the volume and page cited.

This, in turn, led me back to Gallica, on a search for more information about Villedieu, Claude’s friend who was convicted and imprisoned in a convent for the rest of her life. I was initially intrigued because I thought this might be Mlle. de Villedieu, a writer of erotic semi-autobiographical fiction, but no: it’s Madame de Villedieu, the spurned wife of the man the erotic novelist ran off with. Tant pis.

Madame de Villedieu’s testimony indicates that she’d known Claude for some time, and that Claude had been to see the “witch” Madame Voisin at least fifty times. What strikes me as curious is that Madame Voisin insisted — even under horrifying torture, even when her death by burning was certain — that she’d never laid eyes on Claude, much less on Claude’s employer Athénaïs (the Sun King‘s mistress and mother of several of his children).

Madame Voisin.

Why the protection? Voisin was spilling the beans on practically everyone else at court — why not a word about Athénaïs and her maid?

Or is Villedieu’s testimony false? That seems unlikely to me, although she might well have been quite angry to find herself in prison while her friend Claude remained free, courtesy of the King’s protection.

It’s quite an intriguing Affair, and I suspect I’ll be lost in it for some time.

Afternote: all 18 (or more?) volumes of the Archives de la Bastille can be found on Gallica here, available for download.

My eventual conclusion regarding the mystery of Claude and Madame de Villedieu is that the woman Villedieu went to see Voisin with had adopted Claude’s name (for likewise mysterious reasons). Apparently Villedieu, when pressed, described this so-called Claude in terms that were definitely not Claude.