by Sandra Gulland | Apr 22, 2012 | Baroque Explorations |

A few days ago I posted a blog on “Where are all the Pregnant Women?”—noticing that in period paintings very few pregnant women were to be seen, in spite of the fact that woman were often pregnant in those centuries.

Now I’m following up on what they wore:

From the Wikipedia entry on the history of maternity clothes:

“Dresses did not follow a wearer’s body shape until the Middle Ages. When western European dresses began to have seams, affluent pregnant women opened the seams to allow for growth. The Baroque Adrienne was a waistless pregnancy gown with many folds. Aprons were also worn to close the opening left by jackets.”

in French fashion, pregnant women would sometimes wear a “robe battante” or “robe volante“, sometimes called a “flying gown.” All of these were full, wide garments that would cover up any sign of pregnancy. Pregnant women were encouraged to wear loose fitting clothes.

Here is an image of maternity dress from colonial Williamsburg:

Madame de Montespan, the Sun King’s lover, was so often pregnant that she devised a new costume, sometimes credited with being the first maternity gown.

Ironically called “The innocent,” it is described as an ample, beltless gown closed with ribbons tied on each side. (Rather like a smock, I imagine.) As soon as she put it on, people assumed she was pregnant, so it didn’t succeed in disguising her condition, although it no doubt was more comfortable (and she was all about comfort).

It is, unfortunately, rather difficult to find an image of “the Innocent” much less descriptions of the lovely Marquise in this gown, so it is left to our imaginations. If anyone has more specific information on this, please let me know!

by Sandra Gulland | May 1, 2011 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Shadow Queen |

The main character of the novel I’m writing now is relatively unknown. She was the daughter of a theatrical star and a maid to Madame de Montespan, the Sun King’s mistress (the woman we all love to hate).

As part of her duties, she was required to have sex with the King when Montespan was out of sorts.

This is not one of the duties mentioned in The compleat servant-maid, a 17th century book by Hannah Woolley on the work of maids, and dedicated to “all young maidens.”

I just obtained this invaluable guide for maid of all sorts: the Waiting-Gentlewoman, House-keeper, Chamber-Maid, Wet and Dry Nurses, House Maids (in “Great Houses”), Cook-Maids, Scullery-Maids, Laundry-Maids and Dairy-Maids.

Clearly: a lot of maids. “And they all hated me,” claimed my main character Claude, defending herself against accusations of murder and other indecencies.

I adore leafing through guides of this sort; one learns so much:

Do not put any Soap on your Tiffany…

To clean Points and Laces: Take white Bread of half a Day old, and cut it in the middle, and pare the Crust round the Edge, so that you may not damage your Point or Lace when you rube them…

Plus essential recipes for taking away freckles and making teeth white “when very foul or black.”

But nothing about sleeping with your employer’s lover … not one word. Much less what to do when you bear him a child or two. Tant pis.

{Painting: Madame de Montespan in her chateau at Clagny, near Versailles. This post was first aired on Hoydens and Firebrands, a group blog by writers who write novels set in the 17th century.}

by Sandra Gulland | Aug 6, 2010 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

.

.

The problem with writing fact-based fiction is … well … facts. They can really mess up a good story.

I’d read that the Mortemarts, the family of Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan, lived on rue de Rosiers.

Perfect: rue des Rosiers is not far from where Claude des Oeillets, my main character, lived when she first came to Paris. It worked into the story perfectly. Their lives do become entwined; nobody knows how their relationship began, but as a novelist it helped that they were walking distance from one another.

Twice I scouted rue de Rosiers on research trips to Paris. I took many photos, but more than that: I walked the cobbles, dreaming.

Unfortunately, I didn’t read the fine print at the back of one of the texts. Hôtel Mortemart was on another rue de Rosiers, a street that is now named rue Saint-Guillaume … far, far from my heroine Claude.

And that’s not entirely certain, either. Some accounts claim that Hôtel Mortemart on rue Saint-Guillaume was built in 1663?three years after the young women meet.

So where were the Mortemarts living in 1660?

I’ve spent all morning researching possibilities (when I should have been writing). Vivonne, the eldest child, was born in the Tuileries palace. Both high-ranking parents served the King and Queen for three months of the year, and were likely entitled to live there … so that’s a possibility, although they certainly would have had a residence of their own in Paris.

I’m not really sure what I’m going to do about this. I could leave the setting as it is and make a note about the change in the Author’s Note or on my website.

Or I could change it, place the Mortemarts either in the Tuileries or on rue Saint-Guillaume … difficult, and not necessarily good for the story.

I’m still perplexed.

by Sandra Gulland | Feb 17, 2009 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Shadow Queen, Work in Process (WIP) |

On reading the book Strange Revelations, I was convinced that Claude des Oeillets, the heroine of the novel I am writing, was guilty of dealing with the witch Madame Voisin.

The testimonies against Claude recorded in the Bastille Archives are overwhelming in number and detail. How could so many people be wrong?

Les Des Oeillets: une grande comédienne, a biography about Claude des Oeillets and her mother

Now, having read and reread Jean Lemoine‘s Les Des Oeillets: une grande comédienne, une maitresse de Louis XIV, I’m not so sure.

Jean Lemoine is one of those wonderfully careful historians who documents every claim. The book is, in fact, made up of documents: leases on houses, money loaned, money paid, last wills and testaments. The stuff of history.

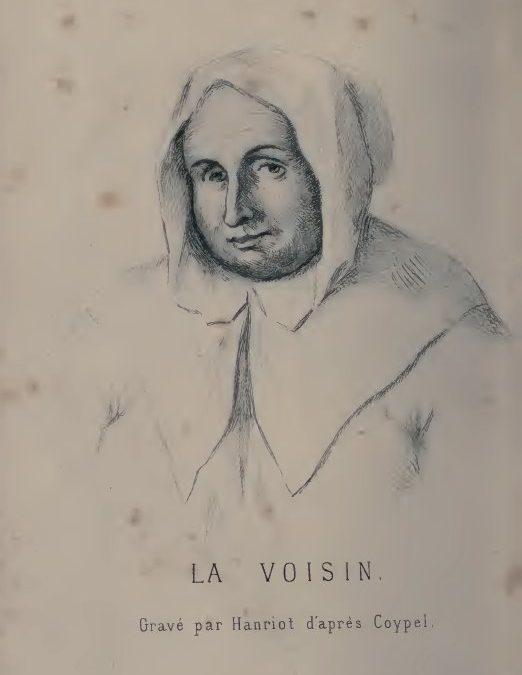

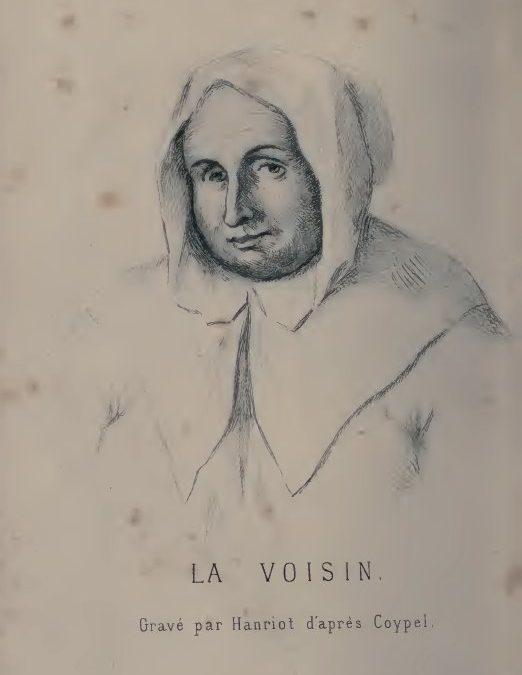

The witch Voisin

What’s telling, to me, is that Madame Voisin insisted, under terrible torture, right up to the day of her execution, that she’d not had any dealings with either Claude des Oeillets or her employer Athénaïs de Montespan.

Voisin had squealed on many, many others at court, most of them high-and-mighty. There was nothing to be gained in not mentioning Claude des Oeillets or Montespan. What would be her motivation?

Possibly: to tell the truth?

The accusations poured in from other prisoners after Voisin’s execution. What I’ve learned from Lemoine’s work is that Claude was called in by Louvois, the Minister of War, and, horrified by what was being said, insisted on being shown to her accusers. She swore on her life that they would not know her.

The “test” was unfortunately mishandled (as noted later by minister Colbert): Claude des Oeillets wasn’t shown to the prisoners with other people. The prisoners had been grilled shortly before about Claude. It was easy enough for them to guess who she was.

She insisted on another meeting with Louvois, pleading her case. This was followed up with a letter, in which she offered explanations. Louvois—who would have been happy to find any evidence compromising Athénaïs de Montespan—was ultimately convinced of her innocence … as was the King and Colbert.

Conclusion: Was Claude des Oeillets guilty?

And so: I’m not yet sure. The reason why Claude’s guilt or innocence is critical is because it directly implicates Athénaïs—the Shadow Queen of France at that time. I’ve ordered Jean Lemoine’s book on Athénaïs and the Affair of the Poisons. Until then, I remain puzzled, unconvinced either way.

Note: this post was written while I was researching and writing The Shadow Queen. If you have read the novel, you will know that I reached the conclusion that Claude (“Claudette”) was both guilty and innocent.