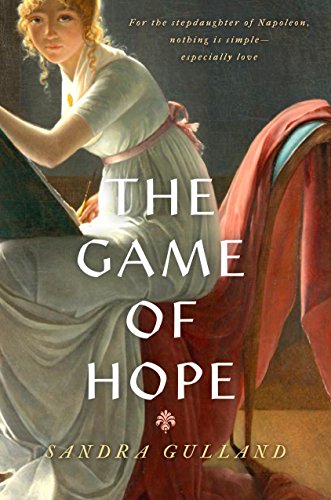

The Game of Hope

For Napoleon’s stepdaughter, nothing is simple — especially love.

Paris, 1798. Hortense de Beauharnais is engrossed in her studies at a boarding school for aristocratic girls, most of whom suffered tragic losses during the tumultuous days of the French Revolution. She loves to play and compose music, read and paint, and daydream about Christophe, her brother’s dashing fellow officer. But Hortense is not an ordinary girl. Her beautiful, charming mother Josephine has married Napoleon Bonaparte, soon to become the most powerful man in France, but viewed by Hortense as a coarse, unworthy successor to her elegant father, who was guillotined during the Terror.

Where will Hortense’s future lie?

Inspired by Hortense’s real-life autobiography with charming glimpses of teen life long ago, this is the story of a girl chosen by fate to play a role she didn’t choose.

The Dream

I saw a man approaching. Cloaked and hooded, he moved with grace in the flickering candlelight.

My heart soared. Father!

He put out one hand, gloved in white leather. Hope was aglow all around him.

But then—as always—his hood fell back, and there was only a bloody stump where his head should have been.

I screamed, gasping for air, my heart pounding.

Mouse and Ém tried to calm me, but I only wept all the harder.

What did my father want?

Why was he haunting me?

Maîtresse rushed into our room in rumpled nightclothes, a shawl thrown haphazardly over her shoulders. “Such screaming, angel! You’ll terrify the Little Geniuses,” she said, putting down her candle. The shadows made her face look like that of a ghoul.

“I’m sorry,” I sobbed, slipping the miniature enamel portrait of my father from under my pillow. Father: so handsome, so elegant, to have died like that, the crowd cheering as his head fell into a basket of wood shavings.

“It’s that same night-fright she always has,” Mouse told her aunt, her voice tremulous.

“That scary dream of her father,” my cousin Ém said.

I looked into Maîtresse’s eyes. She was mistress of our boarding school, quite strict and demanding, yet we all loved her. “With his—” I winced, making a slashing motion across my neck.

“Come here, my sweets,” Maîtresse said, opening her arms.

Dragging their blankets, Ém and Mouse huddled in close. I could feel Mouse trembling. We called ourselves the Fearsome Threesome, but in the dead of night, Fearful Threesome might have been more apt.

“Repeat after me,” Maîtresse said, pulling the blankets snugly around us. She smelled deliciously of vanilla. “We are safe now.”

“We are safe now,” we whispered in unison.

Safe now, safe now, safe now.

But were we? It had been four years since the tyrant Robespierre had been executed, bringing an end to the Terror—but what if it were to happen again? Practically every girl in our school was of the nobility. What was to keep us from being hunted down, having our heads cut off?

I bit my lip, recalling the stench of the dead, heaped like garbage in the square.

Maîtresse clasped my shoulder. The strength of her grip brought me back. “You grew up in a violent time,” she said, her voice soft. “You witnessed things no child should ever have to see. But memories are like words on a wax tablet: they can be erased. You are smart, and creative, and talented. You can become whatever you wish, but first, you must learn to direct your thoughts—even your dreams.” She tucked a stray strand of my hair back up under my nightcap. “Remember: you are safe now.”

Safe now.

I woke before dawn, my thoughts in disarray, my heart aching.

Father, must you frighten me so?

Was I the cause of your death?

I whispered my morning devotions curled up under my blankets, praying that I would never have that dream again.

Praying for the safety of my big brother Eugène, who was a soldier now, fighting with our stepfather’s army in far-away Egypt.

Praying that my stepfather, General Bonaparte, would somehow disappear from my life, lost to the sands of that barbaric country.

Praying that I would become a better person and not have such evil thoughts.

Praying that my mother would stop trying to find a husband for me.

Praying for a horse of my own.

Praying for one of Maîtresse’s delicious chocolate madeleines.

And then, especially heartfelt, praying—sinfully, I know—for the safety of A Certain Someone who was also with the General’s army in Egypt.

Dawn breaking, I slipped shivering out of bed and wrapped myself in a shawl. Quietly, so as not to wake Ém and Mouse, I put kindling and a few sticks of wood on the embers in the fireplace, blowing until it caught fire. I heard a rooster crow and tiptoed to the window to unlatch the shutters. It was cold for early fall—there was a shimmer of frost on the courtyard cobbles.

My thick notebooks were stacked to one side on the study table I shared with Ém and Mouse. I’d been away for three months, tending my injured mother, who had nearly been killed when the second-floor balcony she was standing on collapsed. I had missed the Institute so much. I enrolled at only twelve, shortly after my father had been executed and Maman released from prison. I was now fifteen, Maman was married to General Bonaparte, and my brother was on the General’s staff in Egypt.

Time passed so quickly. And death came quickly, too.

Safe now?

I heard a maid walking the halls, clanging her iron triangle with a metal beater, a grating, high-pitched ringing sound. Six o’clock: time for everyone to wake.

Ém groaned, pulling her covers up over her head.

“Did you sleep, Hortense?” Mouse asked, her voice groggy.

“A bit,” I said, yawning. It had taken me time to get back to sleep after the fright of my dream.

Ém chuckled from under her covers. “You kept me awake the rest of the night,” she said, poking her head out. “Talking lovey.”

“No!” I said—yet flushing. I shared everything with Ém and Mouse, except one secret, which I’d not had the courage to reveal, knowing how foolish they would find me. Me, fifteen, not pretty, not rich, moonsick for the most handsome of the General’s aides. A man I’d only seen a few times and who was now far away in Egypt. A man who hardly knew my name.

“You have a beau?” Mouse asked with that funny little squeak her voice sometimes got.

“I’d tell you if I did,” I said, pulling my clothes out of my travel trunk, yet to be unpacked. It wasn’t a lie, not really. I didn’t have a beau. I only wished I did. One beau in particular.

The triangle sounded a second time, in warning: Get up!

“Your turn to go first, Ém,” Mouse said. Soon we would be on our winter schedule and not have to rise until seven.

Ém, sighing in protest, slipped from under her covers, grabbed her chamber pot and disappeared behind the screen. “Ah me,” she said, “the reds.”

“Do you have what you need?” I asked.

“There are cloths here,” Ém said.

There was a rap at our door. “Citoyenne Hortense, you’re back,” maid Flor said, surprised to see me.

“She arrived last night,” Mouse said, buried back under her covers. “In the dark.”

“How is your lovely mother?” Flor asked, filling each of our porcelain wash basins with steaming water.

“Improved.” Grâce à Dieu. “She can stand up now.”

As soon as Flor left, the triangle clanged a third time: Get dressed!

Mouse sat up, groping for her spectacles on the table beside her bed.

“It’s a bit chilly,” I said, slipping on my flannel chemise and a wool school gown over it. The long white dress was starting to feel small for me around the chest. (Yes.)

I was arranging my multicolored sash—the sash worn by those of us who had completed all the levels (the Multis, we were called)—when another servant appeared, the country girl who worked in the laundry room. “A frosty morning, girls. Émilie, you will want your lovely shawl. I stitched on your initials and number.” She closed the door behind her.

“It’s new, Ém?” I asked, passing the shawl over to her. A delicate shade of rose, the thick, luxurious cashmere was well beyond our means.

“It was a gift from her husband,” Mouse said with a giggle.

Her husband. That sounded so strange to me. Ém had been introduced to Captain Antoine Lavalette only sixteen days before marrying him, all arranged by the General and my mother. A few days later, Lavalette had left for Egypt, and shortly after that, I had gone south, and I’d not seen my cousin since.

“It’s beautiful,” I said with envy.

Ém looked stricken, her doe eyes glistening. “I prefer my old one,” she said, pulling her moth-eaten, itchy wool shawl out of her trunk.

I caught Mouse’s eye. She raised her eyebrows as if to say, I don’t understand either.

“Don’t look like that,” Ém said with a flare of surprising emotion. She was usually placid (unlike Mouse and me). “I hate how everyone goes on about me being a married woman.”

“But Ém, you are a—”

“I’m not,” she said, cutting me off. “Not really.”

How could she say that? I had been present at the ceremony in our grandparents’ house here in Montagne-du-Bon-Air.

“What do you mean, Ém?” Mouse asked, pushing up her heavy glasses.

“It’s just that I’m still . . .” Ém flushed.

“Chaste?” I whispered.

Ém answered with a slight nod.

I was surprised. It was common for girls who married young to wait until puberty before consummating their union, but Ém was seventeen, and womanly besides. I was about to say that that didn’t mean she wasn’t married, but the seven o’clock triangle sounded.

“Let’s not be late,” Mouse said from the door.

“Sandra Gulland’s first foray into YA literature is a huge success. Having written an internationally bestselling trilogy of adult books based on the life of Josephine Bonaparte…, Gulland’s knowledge of this time period is extensive. Inspired by Hortense’s autobiography, she has written a historically detailed and truly intriguing story of this teenage girl from 18th-century France. Readers who are historical-fiction buffs or fans of the Napoleonic era will truly appreciate Gulland’s skill at recreating this fascinating period in history and empathize with Hortense at being thrown into a world that was not of her choosing.” — Sandra O’Brien, editor of Canadian Children’s Book News.

“Gulland has built a career writing historical fiction for adults, including a bestselling trilogy about Josephine Bonaparte (Hortense’s mother). Her pitch-perfect balance of lush period details and character-driven narrative shines again in The Game of Hope. — Quill & Quire

“Gulland, who’s clearly done her research, includes plenty of documented moments and people from Hortense’s life, which cultivates a rich sense of atmosphere . . . Teen fans of historical fiction fascinated by the period will find plenty to appreciate here.” — Booklist

“Elegantly written … Hortense’s lively and warm nature makes her an appealing narrator… Her coming of age and the accompanying shifts in her relationships are among the book’s highlights. … Over the course of the book, Hortense gains greater perspective on the stepfather she disdains, the father she adored but barely knew, and even her challenging schoolmate, Caroline. … the novel strikes the right balance between Hortense’s youthful innocence and the tense uncertainty of the era. It creates a convincing portrait of a young woman learning about her world, navigating through limited choices, and fulfilling her ambitions as much as she’s able.” —Sarah Johnson, Reading the Past

Cyn’s Workshop Review: “[The Game of Hope] captures the essence of the period. It is not just a story about a girl; it is about the time; it is about the people whose lives she touched and about the changes spurned from the revolution. That is what makes it so grand and captivating.”

Krimsuun Pages: “Sandra Gulland’s writing is enchanting and beautiful.”

Gulland, who’s clearly done her research, includes plenty of documented moments and people from Hortense’s life, which cultivates a rich sense of atmosphere . . . Teen fans of historical fiction fascinated by the period will find plenty to appreciate here. — Booklist

All of the characters are lovely and I fell in love with them so fast. There was just something about the personalities of the girls at the Institute that I feel we would have been great friends. — from a long review on the blog Milk and Honey by Erin B.

This book was fantastic! —Sarah Rodriguez on GoodReads

The Game of Hope was a book I was sad to see end. — Margaret on NetGalley

Loved this read! It had me hooked! —Chelsea M on NetGalley

I enjoyed this book so much that I’ve read it twice already! — Leslie U on NetGalley

Sandra Gulland has done it again … [Her] understanding of the very real people about whom she’s writing is so profound she practically breathes life into them. — Mary I on GoodReads

This great historical YA is timely and yet of another time. … [It] shows us how to look to the past and see hope in the future. The Game of Hope is excellent for teenage girls or anyone who loves a great story. —Vanessa Van Decker on GoodReads

Hortense’s world was developed in such a way that at the conclusion, I had no desire to leave it. — Christine on GoodReads:

I absolutely loved this look into the life of Hortense de Beauharnais, step-daughter of Napoleon … — Irene O’Hare on GoodReads

Sandra Gulland has yet to disappoint. … What I love, besides the historical detail and wonderful characterization, is the matter-of-fact way this story treats the facts of life – menstruation, sex, etc.— Nefertari on GoodReads

Here are some links to articles about Hortense if you wish to learn more about her:

- On Hortense’s creative process and how “Partant pour la Syrie” came into being.

- Madame Campan’s school

- A special exhibition at Malmaison on Josephine and Napoleon’s house reveals a treasure trove of information

- On the Phantasmagoria — the first horror picture show

Click here if you wish to see a current-day Google map of all the places mentioned in The Game of Hope.

You can see many portraits of the people in Hortense’s life on my Pinterest boards:

- Hortense’s World

- Portraits of Hortense

- Madame Campan and her schools

- French Madeleines

- The Napoleonic Era

- Josephine

- The Bonaparte Clan

- Napoleon

- The French Revolution

- Josephine’s beloved Malmaison, then and now

- All things Napoleon

I wrote a number of blog posts about the process of researching and writing The Game of Hope. Someday I will collect them into one little booklet, but for now, here are a few:

- Tilling new ground; preparing to write

- Juggle this! On plotting, beginning the 1st draft, making a final edit, tweaking a shout line and filling out a beastly author questionnaire …

- On Author Questionnaires, First Pages, daily word count for my YA about Hortense, and wonderful grandchildren, all at once

- “What am I working on?” Question #2 in the Writers’ Blog Tour

- The evolution of The Game of Hope (how it all came about, from start to finish)

If you would like to read more about the life of Hortense and her family, I recommend you read my Josephine B. Trilogy, which is the life story of Hortense’s mother Josephine. The first book in the Trilogy — The Many Lives & Secret Sorrows of Josephine B. — begins with Josephine’s sentence, written in her diary: “I am fourteen today and unmarried still.”

I have posted a full bibliography of works I consulted in writing The Game of Hope here, but the works I would mostly recommend listed below. A number of them are out-of-print and expensive to buy, in which case I recommend getting them through your local library’s interlibrary loan service.

- A Rose for Virtue, a novel about Hortense written by Norah Lofts.

- Daughter to Napoleon; A biography of Hortense, Queen of Holland, by

- The Memoirs of Queen Hortense, in two volumes, edited by Jean Hanoteau and translated by Arthur K. Griggs. Other editions can be found online, but they are not nearly as good, so I recommend getting it through interlibrary loan or buying it used at Abebooks.com.

- The Letters of Madame Campan can be found online, but only in French. The Celebrated Madame Campan by Violette M. Montagu is excellent

- There is little available on the life of Madame Lenormand, but there is one chapter on her life in A Wicked Pack of Cards; The Origins of the Occult Tarot by Decker and Depaulis. Additionally, a great deal may be found on the Net.

- To read more about Hortense’s beloved brother, read Eugène de Beauharnais; The Adopted Son of Napoleon, by V.M. Montagu.

- For beautiful visuals of the Napoleonic age, I recommend The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire, 1789-1815 by Charles Otto Zieseniss. It is expensive to purchase, even used, but fortunately, it can an be found online.

- How does Hortense view her mother? Her father? Her stepfather?

- Ghosts are a theme throughout The Game of Hope. Are they real? Imagined?

- Describe the post-Revolutionary world. What do you think Napoleon offers that people find appealing?

- Is Hortense fair in her assessment of her stepfather? What about her assessment of her birth father?

- Which character did you most strongly connect with? Why?

- It what ways are women’s rights a theme in this novel? How are things different today?

- Discuss Caroline’s character. Did you like her? How did she impact the story?

- If you have read the Josephine B. Trilogy, in what ways does this novel differ?

- Which of Sandra Gulland’s novels have you liked the best, and why?