Who was Louis XIV’s father?

A reader asked about Louis XIV’s father:

Has anyone given serious consideration to the possibility that Henri d’Effiat, Marquis de Cinq-Mars, was the biological father of Louis XIV?

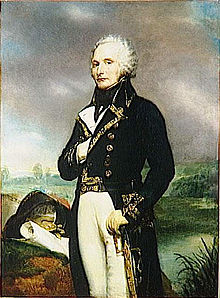

Richelieu went to his close friend D’Effiat specifically to bring his handsome 18-year-old son into the court. Cinq-Mars was given the title “master of the wardrobe” which provided him access to the royal bedroom.

One year later, Anne was with child. Cinq-Mars was accused of conspiring against the king (with Anne) and beheaded.

Cinq-Mars also was, coincidentally, “the Favorite” in the biblical sense with the gay Louis XIII.

Henri de Cinq-Mars

My go-to-person for questions regarding Sun Court history is historian Gary McCollim. He generously provided this answer:

The answer to the question is simple:

No one ever accused Cinq-Mars of being Louis XIV’s father because of a simple matter of dates.

Louis XIV was born on 5 September 1638. Doctors had estimated in January that the queen was six weeks pregnant which meant that conception took place in late November 1637. The king and queen had been at Saint-Germain-en-Laye throughout the month of November and returned to Paris on 1 December. Doctors expected the child’s birth sometime between 23 to 28 August 1638.

Henri de Cinq-Mars was not appointed master of the king’s wardrobe until March 1638 when the queen was already pregnant.

While the appointment might have given Cinq-Mars access to the king’s bedroom, it did not give him access to the queen’s bedroom. Also, Anne of Austria for reason explained below was reluctant to join any conspiracy after the birth of her son. Some sources say she may even have been instrumental in exposing the Cinq-Mars conspiracy to Richelieu.

No serious historian today thinks that Louis XIV had any other father than Louis XIII.

Documentary evidence shows that Louis XIII and his wife, Anne of Austria, made up their differences in August 1637. Anne confessed to her participation of in some of the plots around the throne and of communicating with her brother the king of Spain. She promised to cease such behavior. Her near brush with disgrace persuaded her to abandon her plots and become the wife of her husband in fact and deed, so to speak. Louis XIII was convinced by Richelieu that the plotting would continue as long as he had no male heir. Thus, marital relations resumed between the two people in late summer 1637. The king had dedicated his kingdom to the Virgin Mary in February 1637 while praying for a male heir.

It has been fashionable among people today at a time when gay rights are in demand to think of Louis XIII as a homosexual and thus imply that he was somehow unable to father a child. We know that is not true. In fact, he was bisexual. He did have female favorites to whom he was loyal as well.

In any case, after the birth of Louis XIV the royal government put out the propaganda that his birth was miraculous, a result of prayers and supplications to God and the Virgin Mary.

Louis XIV was given the name Dieudonné (God-given).

There were many people who were surprised that the queen had gotten pregnant when she did, but no one at the time accused her of any improper behavior. There were people, such as the king’s brother Gaston and his cousins the Condes who had strong reasons to be wary of a surprise pregnancy as they were the heirs to the throne. Louis XIV’s birth pushed them further back in the line of succession.

Yet, Gaston and the Condes never made any accusations about Anne of Austira’s surprise pregnancy at the time or later during the Fronde.

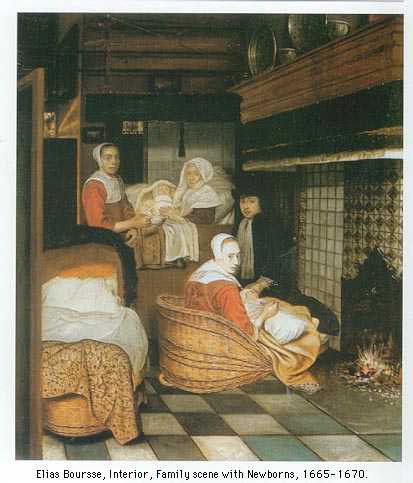

A story emerged of the king Louis XIII being trapped in a terrible rainstorm on the night of 5 December 1637 and being forced to seek shelter in the Louvre where the only bed fit for the king was Anne of Austria’s.

Thus, implying that the conception took place that night. There is no proof that this story is true. Yet, it lives on in the popular imagination, plays have been written about it. In any case, Louis XIV grew up surrounded by this myth of his miraculous conception.

In the 1690s, however, when France was at war with all of Europe, his enemies the Dutch began to question the story and insinuated that Anne of Austria (who had died in 1666) had gotten pregnant from a man other than her husband.

One propaganda piece said the father was someone with the initials Le C. D. R. meaning Cardinal de Richelieu. Soon other candidates were accused of being the real father. Cardinal Mazarin was accused (he had died in 1661) but documentary evidence shows that he was in Italy from 1636 until 1640. Since the 1690s, historians have blamed other people, some famous like the Duke of Buckingham (died 1628) or the Duke of Beaufort (died 1669), and others less well known to be Louis XIV’s real father.

This whole story shows the power of propaganda to drive people’s imaginations without a shred of historical evidence.

In any case, Cinq-Mars has never been named as a possible father for the reasons I showed above.

Books that can shed light on this subject are:

Jean-Vincent Blanchard, Eminence (2011)

A. Lloyd Moote, Louis XIII, the Just (1989)

Ruth Kleinman, Anne of Austria, Queen of France (1985)

Claude Dulong, Anne d’Autriche (2000)

Jean-Christian Petitfils, Louis XIII (2008)

Gary is the author of: Louis XIV’s Assault of Privilege: Nicolas Desmaretz and the Tax on Wealth, published by the University of Rochester Press/Boydell & Brewer.

His book discusses the difficult situation of royal finances at the end of the reign of Louis XIV, and how the king was forced to turn to Nicolas Desmaretz, a man who had been dismissed from the royal government in 1683 following the death of his uncle, the great Colbert.

His book discusses the difficult situation of royal finances at the end of the reign of Louis XIV, and how the king was forced to turn to Nicolas Desmaretz, a man who had been dismissed from the royal government in 1683 following the death of his uncle, the great Colbert.

Desmaretz had been critical of the royal government’s policies that increased the tax burden of the poorest elements of French society. He returned to the French government in 1703 as an assistant to the finance minister and became finance minister himself in February 1708. The book shows how Desmaretz and his staff were in contact with reformers and advocates of new policies. Out of this atmosphere of declining tax revenues, increasing defeats in the War of the Spanish Succession, and the refusal of France’s enemies to make a reasonable peace offer, Desmaretz decided to create a tax on the income produced by the ownership of property, in other words, a tax on the wealthiest elements of French society, to provide the funds necessary for France to survive the war and bargain for a reasonable peace.

After the war, Desmaretz was working to alleviate France’s debts in a way that could have changed the history of the eighteenth century except that Louis XIV died and Desmaretz was dismissed as the government turned to riskier schemes that boxed the royal government in for the rest of the eighteenth century leading to the Revolution.

About the author: Gary is a retired former employee of the US federal government He was educated at Muskingum College and received his doctorate in history from The Ohio State University studying under John C. Rule, a recognized expert on Louis XIV.

As always: thank you, Gary!

See also: The conception of Louis XIV.