by Sandra Gulland | Oct 31, 2020 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I recently read an article by the elusive Ryan Holiday, a professional book researcher. He made one very important point—at least to me. He said that the first step in researching is to acquire a research library which will include books that you will likely never read. He calls it an anti-library.

We all have books and papers that we haven’t read yet. Instead of feeling guilty, you should see them as an opportunity: know they’re available to you if you ever need them.

This is exactly what I do: buy too many books, print out too many articles, and read only a fraction of them. So now I’m going to stop feeling guilty about it.

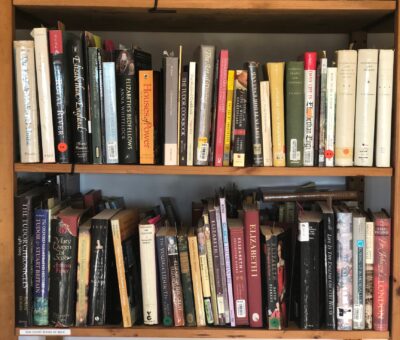

Two of six shelves for the WIP. Note the white tag in the lower left. It reads: “Sun Court books at the back.” In other words, I’ve run out of shelf space.

One of my rules as a reader is to read one book mentioned in or cited in every book that I read.

I often scour footnotes for references to books the author has relied on. Lately, I’ve acquired two books in this way and they have proved to be invaluable.

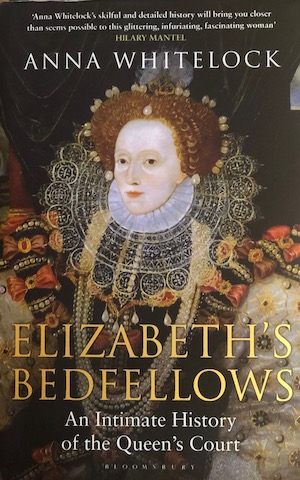

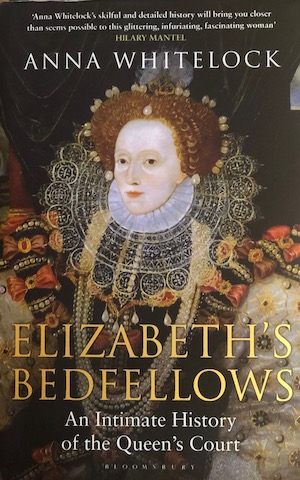

One is Elizabeth’s Bedfellows; An Intimate History of the Queen’s Court by British historian Anna Whitelock. She was one of the experts on a documentary on Elizabeth I. I ordered her book and immediately on opening it saw details I badly needed to write a scene that had me stumped. I will only need a few chapters of this book—at least for this WIP—but they are gold to me.

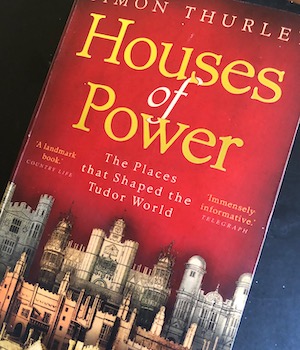

The other book is a paperback edition of Houses of Power; The Places the Shaped the Tudor World by Simon Thurley. (Note that this book can be hard to find, at least in North America. I finally found a used copy on Abebook.com.)

I have a number of works by this wonderful historian, but this is the book that made me gasp. It’s full of the floorplans of Tudor palaces at that time, and amazing details as well. In no time flat, I began to mark it up.

A research trick I use: for a print book I own, if the “search me” feature is available on Amazon, I will add it to a list. Say I’m looking for events in 1553: I’ll search for that year in the Amazon link of the book—note that it has to be the print edition—and this will give me the pages to go to in my copy of the book. It’s an instant index to the type of thing that would never show up in an official index.

Since posting this, I’ve had the pleasure of listening to a podcast interview of Professor Simon Thurley on The Tudor Travel Show. Fascinating! He also has two free online lectures I’m looking forward to listening to: Tudor Ambition; Houses of the Boleyn Family and Ruling Passions: The Architecture of the Cecils. As well, he has launched an invaluable research website that provides up-to-date information on royal palaces: RoyalPalaces.com.

Dr. Sarah Morris of The Tudor Travel Show (above) is an invaluable source of information, both through her Tudor Travel videos and podcasts, but also through her writing: her two novels about Anne Boleyn—Le Temps Viendra (I and II)—as well as the abundantly detailed non-fiction account In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, written together with On the Tudor Trail podcaster Natalie Grueninger.

The art at the top is from Bibliodessy.

by Sandra Gulland | Sep 19, 2020 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, Resources for Writers, The Writing Process, Tudor England, Work in Process (WIP) |

I’ve been stuck for nearly a week over a chapter in the WIP. (The whip, I think ruefully, as I type those letters.) The problem has many causes. One is that I have a stubborn need to know where-the-heck my heroine (Elizabeth Tudor, in this instance) is, in fact. It’s a period of only two days, and historians don’t provide the details—which should lead me to suspect that the information simply isn’t available.

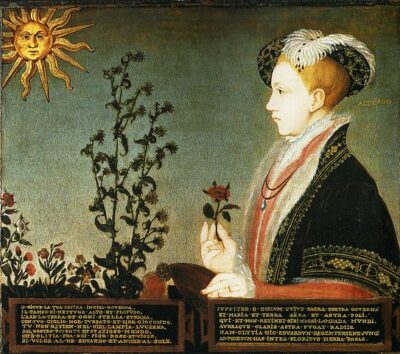

Edward VI with flowers by William Scrots, circa 1550

It’s an important moment, so I’m surprised not more is known. Fifteen-year-old King Eddie VI has died, and (after something of a bloodless battle) his half-sister Mary has been proclaimed queen.

Portrait of Queen Mary I of England by Antonis Mor, 1554.

Mary’s much younger half-sister Elizabeth (not yet twenty), is now the heir to the throne. She is riding out to meet Mary—to bow before her sister queen.

Elizabeth, a good ten years later.

First, the frazzled timeline

This is what is said:

On Friday, July 28, 1553, news of her sister Mary’s accession reaches Elizabeth at Hatfield. (Tudors—Twenty-eight Days to Wanstead by Alan Cornish)

This website account is fantastic, but this one date is unlikely, in my view, because Mary was proclaimed queen in London on July 19.

According to historian Tracy Borman in Elizabeth’s Women (page 136), Elizabeth wrote Mary on that day to congratulate her, but also …

Showing all due deference, she also humbly craved Mary’s advice as to whether she ought to appear in mourning clothes out of respect for their brother, Edward, or something more festive.

(This is the type of detail I relish.)

It would have taken time for Elizabeth’s missive to reach Mary, for she was in the northeast, at her Framlingham castle, already attending to matters of state business and debating whether or not to go to London. Some advised her that it would be wise to return soon while the public was so enthusiastic about her. On the negative side, it was stinking hot in London and there were rumours of plague.

Mary was apparently prepared to be magnanimous in her triumph. She therefore invited Elizabeth to accompany her to London. (Borman’s Elizabeth’s Women)

Mary set out for London on Monday, July 24. It was a long journey: Ipswich (two nights), Colchester (one night), Newhall (three nights), Ingatestone (two nights), Havering (one night), finally arriving at Wanstead House on Tuesday, August 1, where she welcomed Elisabeth the next day, on August 2. (This overnight stay is rarely mentioned in biographies.) Together they set out for London on Thursday, August 3—with a combined entourage of over twenty thousand—arriving late that afternoon in London.

Elizabeth set out to meet Mary on Saturday, July 29, and by most accounts, she stayed for only one night in London before heading out the next day, Sunday, July 30, to meet Mary.

The puzzle

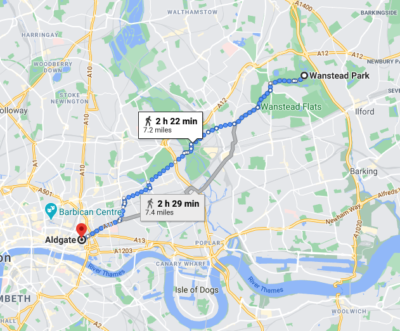

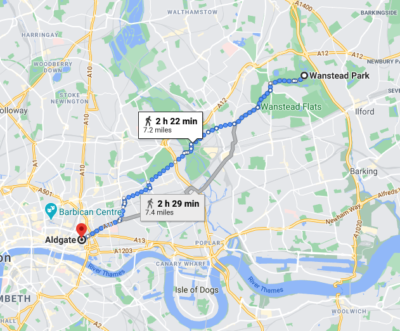

The journey from the London gate to Wanstead takes but a few hours on foot. (See my note below.) If Elizabeth was in London on July 29 for only one night, and met Mary on August 2 near Wanstead, where was she on July 31 and August 1? She was travelling with an entourage of over a thousand, so it was not as if she could drop in just anywhere.

This question foolishly cost me several days of work. I finally found support for the likelihood that Elizabeth had simply stayed at Somerset House, her new (to her) manor in London, for the full three nights. (Elizabeth I; The Word of a Prince, by Maria Perry, page 83.)

Second, the frazzled meet-up

A few historians state that Elizabeth stayed with Mary for one night at Wanstead House, and the consensus seems to be that they met on the road, and that Elizabeth dismounted and knelt in the dirt before Mary.

The problem with writing fact-based fiction — at least for me — is that things have to make sense. So now my question was: If Mary was expecting Elizabeth at Wanstead House, why did she meet her on the road? I didn’t want to spend another week on this, so I decided to sketch out a draft where they meet on the road, Elizabeth kneels, and they move on to Wanstead House from there.

But then what?

However Elizabeth and Mary meet, the sheer size of their entourages boggled my mind. Elizabeth had an entourage of over a thousand, but it was nothing to compare with her sister’s following. Imagine:

In the late afternoon of 3 August, Mary Tudor set out in procession from Wanstead to take possession of her kingdom. Those who stood along the processional route to London were astounded by the great number in her party. Mary had an escort of some ten thousand people with her – ‘gentlemen, squires, knights and lords’, and not to mention, the various peeresses, clergymen, judges, heralds, and foreign dignitaries come to pay her tribute.

—The Turbulent Crown: The Story of the Tudor Queens by Roland Hui (p. 322).

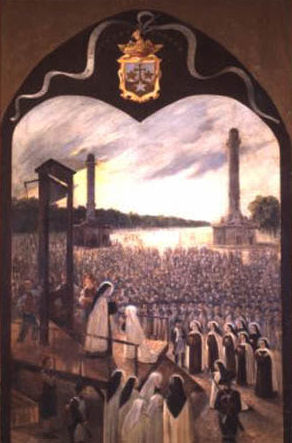

This is an image of the coronation procession of Elizabeth’s brother, King Edward VI. Imagine the traffic congestion!

This was at a hot time of year: the dust clouds of Mary’s procession coming through rural Essex must have been horrendous.

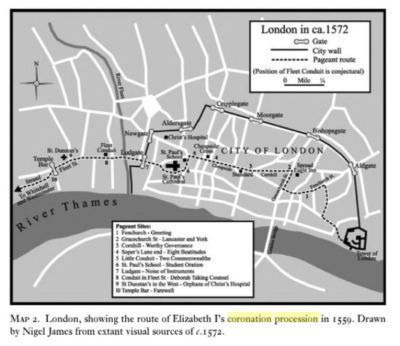

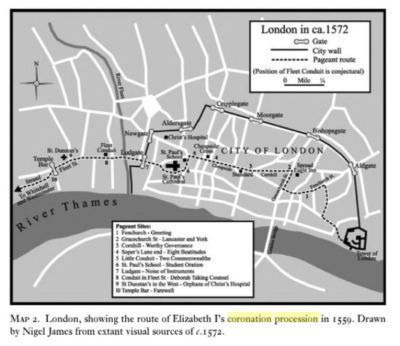

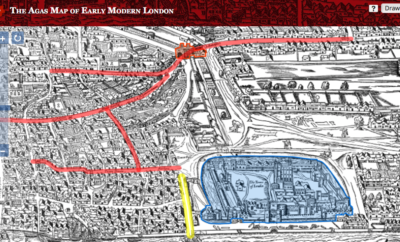

It did not take long to run into another time-consuming research question: Once they reach London, followed by well over ten thousand, what route do they take to the Tower of London? I decided that one hint might be to find out what the traditional route for a regal procession to or from the Tower of London might have been. This (eventually) led me to an amazing book (in four volumes): The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth by John Nichols on https://books.google.ca. On page 115 of Volume 1, there is this map:

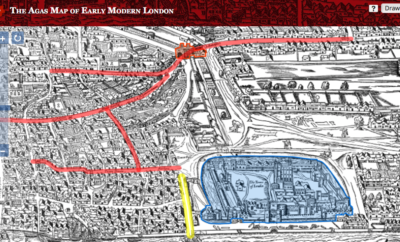

Knowing this, I was able to chart the route on the fabulous interactive Agas Map of Early Modern London: Entering at Aldgate, they would wend their way down Aldgate Street, take the left fork onto Fenchurch Street, left onto Mark Lane, right on Tower Street and right again on Petty Wales to the entry into the Tower.

To the Tower!

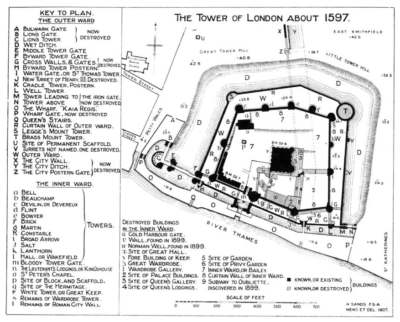

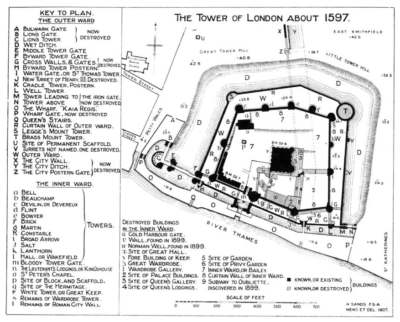

My second puzzle, also solved today, was to determine where were the queen’s apartments in the Tower of London. Several maps later, including the one below, I discovered that the queen’s apartments were in the lower right-hand corner of the Tower premises, fairly cut off from any unpleasantness.

For what queen’s apartments might have looked like, I found an excellent blog post on The Tudor Travel Guide: The Royal Apartments at the Tower & the Scandalous Killing of Anne Boleyn.

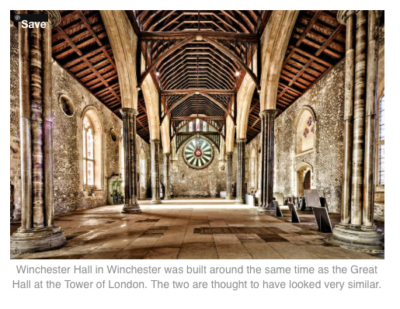

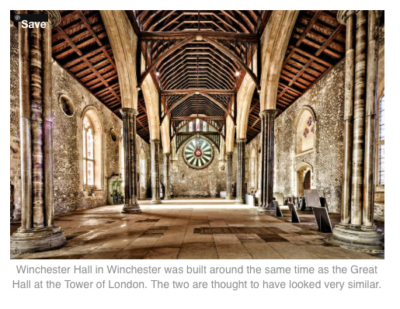

In addition to great details, the site provides this image of what the Great Hall at the Tower likely looked like:

This helps give me a feeling for what the rooms beyond might have been like.

How much of this is likely to end up mentioned in the novel? Likely very little, but knowing what’s what helps me imagine the scenes.

Confession: two research tricks

To estimate approximate walking distances, I find it useful to use maps.google.com.

(Too bad maps.google doesn’t have an “on horseback” option. For this, I suspect that somewhere between “walking” and “by bike” might be an approximation, given all the stops horseback travel requires to give the horses rest, food, and water, or possible exchanges.)

Another part of knowing what’s what is determining when the sun rises and sets, and (particularly in this time) when the moon is full. I can’t track that for 16th century England, so instead, to at least keep the sun and moon on realistic trajectories I’m using the current calendar for the UK using this fantastic site: timeanddate.com.

And so? So now “all” I have to do is write the #%&@ scenes.

Resources mentioned

Books Google

Elizabeth’s Women by Tracy Borman.

Elizabeth I; The Word of a Prince, by Maria Perry.

Google Maps

The Agas Map of Early Modern London

The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth by John Nichols.

The Royal Apartments at the Tower & the Scandalous Killing of Anne Boleyn, a blog post on The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Turbulent Crown: The Story of the Tudor Queens, by Roland Hui.

Timeanddate.com

Tudors — Twenty-eight Days to Wanstead by Alan Cornish. This website post is a wonderfully detailed account.

by Sandra Gulland | Jul 24, 2020 | Adventures of a Writing Life, On Research, Work in Process (WIP) |

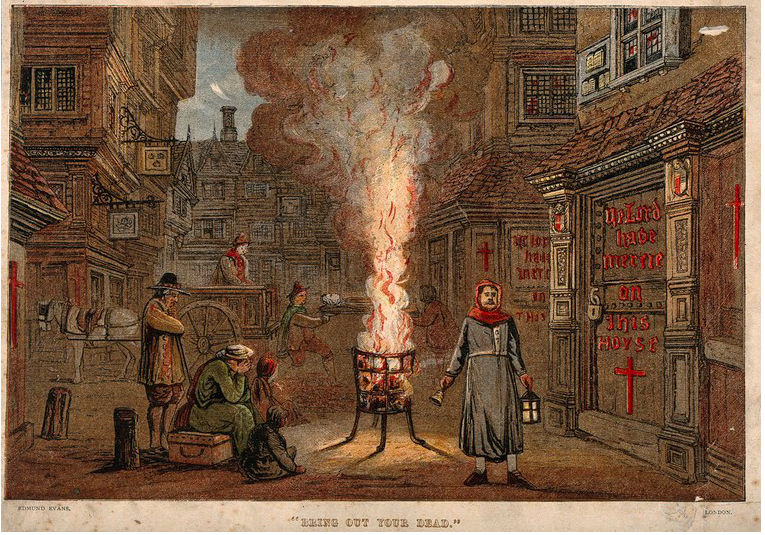

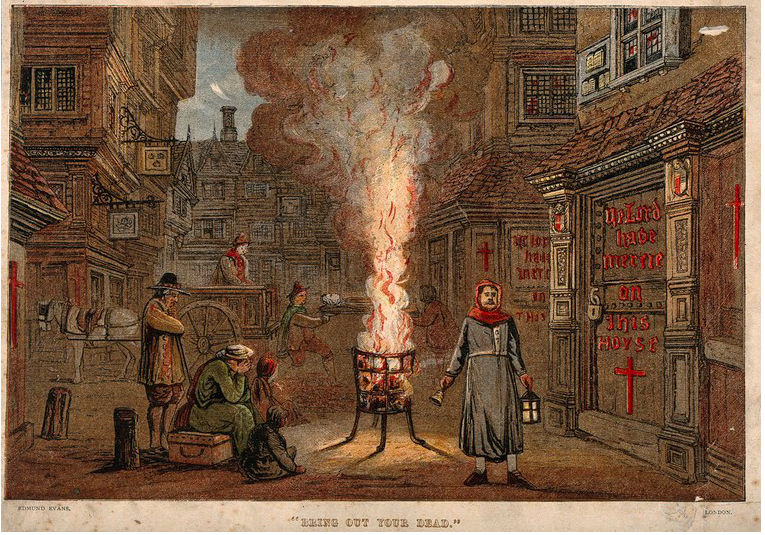

The novel I’m writing now is set in mid-16th century England. During this time period episodes of black plague and the quickly lethal “sweating sickness” came and went. With each epidemic, enormous numbers of people died.

Long ago, when I started to research, these events were simply blips on a timeline. With the advent of our Covid-19 world, such facts became far more vivid to me. I hadn’t understood the fear and heightened state of caution epidemics caused.

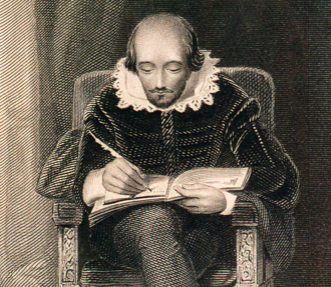

A 16th-century story to set the stage: a man and woman in a village in England lost children to the plague. Another child was born, and when plague returned to their town, they sealed shut the windows and doors of their home. Thanks to their precautions, their child survived: his name was William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare wrote “King Lear” (and “Macbeth,” and “Antony and Cleopatra”) during plague years when the London theatres closed down. (The rule was that once the death toll went over 30, playhouses had to close.) In short, he was out of work and had time on his hands.

“King Lear” is one of his bleakest plays, written while living in a bleak time:

The mood in the city must have been ghastly – deserted streets and closed shops, dogs running free, carers carrying three-foot staffs painted red so everyone else kept their distance, church bells tolling endlessly for funerals … (The Guardian, March 22, 2020)

Plague also changed the nature of the plays he wrote. Plague killed off men in their 30s, so the demographic of both his actors and audience changed.

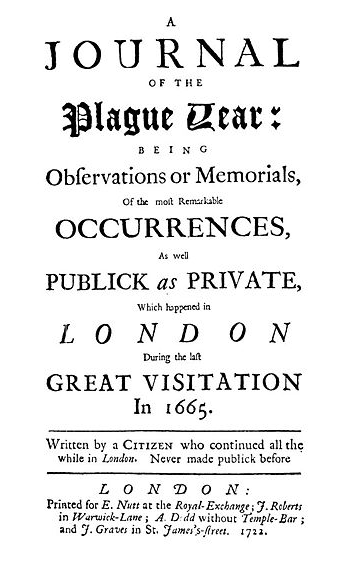

Although A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe is not, in fact, a contemporary account—Defoe was a master of what I would call fact-based fiction—it is thought to have been well-researched. I was struck, reading it, how well-organized England was in combating epidemics. For example, if infected, people were prevented from leaving their homes. One needed a certificate of health in order to travel. Interesting!

Certainly, it is reminiscent of what we are going though today:

City authorities are sane and composed concerning the spreading plague, and distribute the Orders of the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the City of London. These set up rules and guidelines for the arrangement of searchers and inspectors and guardians to monitor the houses, for the quieting down of contaminated houses, and for the closing down of occasions in which enormous gatherings of individuals would assemble.

Here’s a truly contemporary word of caution from 1665:

This poem by U.S. poet Daniel Halpern was published—astonishingly—seven years ago in Poetry Magazine. (Likewise astonishingly, he doesn’t remember writing it.)

Pandemania

There are fewer introductions

In plague years,

Hands held back, jocularity

No longer bellicose,

Even among men.

Breathing’s generally wary,

Labored, as they say, when

The end is at hand.

But this is the everyday intake

Of the imperceptible life force,

Willed now, slow —

Well, just cautious

In inhabited air.

As for ongoing dialogue,

No longer an exuberant plosive

To make a point,

But a new squirrelling of air space,

A new sense of boundary.

Genghis Khan said the hand

Is the first thing one man gives

To another. Not in this war.

A gesture of limited distance

Now suffices, a nod,

A minor smile or a hand

Slightly raised,

Not in search of its counterpart,

Just a warning within

The acknowledgement to stand back.

Each beautiful stranger a barbarian

Breathing on the other side of the gate.

Stay safe! Stay healthy!

Links of interest:

Shakespeare in lockdown: did he write King Lear in plague quarantine?

Shakespeare wrote King Lear in quarantine. What are you doig with your time?

5 People Who Were Amazingly Productive in Quarantine

What Shakespeare Teaches Us About Living With Pandemics

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 30, 2018 | On Research, The Game of Hope |

This bibliography is the list of books and magazine articles I consulted in writing The Game of Hope. Some of them I consumed, others I simply scanned, looking for one particular fact. There are a number I’ve not listed — the annotated works of Jane Austen, for example, a number of which I consumed. Also, please note that I am not an academic, and have not used correct bibliographic style. Should you wish any further information about any of these references, please contact me.

- —. De la naissance à la glorie: Louis XIV a Saint-Germain, 1638-1682. Musée des Antiquités Nationales; Saint-Germain-en-Laye; 1988.

- — . A Guide to the Wrightman Galleries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; NY; 1979.

- — . Decorum; A Practical Treatise on Etiquette & Dress of the Best American Society 1879. Westvaco; 1979.

- — . Eugène de Beauharnais; honneur & fidélité.

- — . The Gentlemen’s Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness. Hesperus Press Ltd.; London; 2014 (but first published in 1860).

- — . The reign of terror: a collection of authentic narratives of the horrors committed by the revolutionary government of France under Marat and Robespierre, Volume 1. W. Simpkin and R. Marshall; place; January 1, 1826.

- —. Joséphine et Napoléon; L’Hôtel de la Rue de la Victoire. Musée national des châteaux de Malmaison et Bois-Préau; Paris; 2013.

- —. La Reine Hortense; Une femme artiste. Malmaison; Paris?; May 27 – September 27 1993. —. Lucien Bonaparte et Ses Mémoires, 1775-1840. G. Charpentier; Paris; 1882.

- —. Madame Campan (1752 – 1822). Château de Malmaison; Rueil-Malmaison; 1972. Catalog of an exhibition.

- Abbott, John S. C. Hortense.

- Al-Jabarti. Napoleon in Egypt. Translated by Shmuel Moreh. Markue Wiener Publishing; Princeton & NY; 1993.Alméras, Henri d’. La Vie parisienne sous le Consulat et l’Empire. Cercle du Bibliophile. Albin Michel; Paris.

- Anderson, James M. Daily Life during the French Revolution. Greenwood Press; Westport; 2007.

- Atteridge, A. Hilliard. Joachim Murat, marshal of France and king of Naples. Brentanos; NY; 1911.

- Aulard, A. Paris pendant la Réaction Thermidorienne et sous le Directoire. Tome V (July 21 ’98 to Nov. 10 ’99) Maison Quantin; Paris;1902.

- Aulard, A. Paris sous le consulat. Vol. I. Maison Quantin, Paris; 1903.

- Baldassarre, Antonio. Music, Painting, and Domestic Life: Hortense de Beauharnais in Arenenberg. An article published in Music in Art XXIII/1-2 (1998).

- Bear, Joan. Caroline Murat. Collins; London; 1972.

- Bergh, Anne de, and Joyce Briand. 100 Recipes from the Time of Louis XIV. Trans. by Regan Kramer. Archives & Culture; Paris; 2007.

- Bertaud, Jean-Paul. Historie du Consulat et de l’Empire; Chronologie commentée 1799-1815. Perrin; Paris; 1992.

- Bouissounouse, Janine. Julie: the life of Mlle de Lespinasse. Appleton-Century-Crofts; NY; 1962.

- Branda, Pierre. Joséphine; Le paradoxe du cygne. Perrin; Paris; 2016.

- Bretonne, Restif de la. Monsieur Nicolas; or The Human Heart Laid Bare. Translated, edited etc. by Robert Baldick. Barrie and Rockliff; London; 1966.

- —. Sara. John Rodker, for subscribers; London; 1927.

- Bruce, Evangeline. Napoleon and Josephine; The Improbable Marriage. A Lisa Drew Book. Scribner; New York; 1995.

- Buchon, Jean Alexandre. Correspondance Inédite De Mme Campan Avec La Reine Hortense, Tome 1. (Replica.) Book Renaissance; 1835.

- Burney, Fanny, edited by Joyce Hemlow. Fanny Burney; Selected Letters and Journals. Oxford Univ. Press; Oxford; 1987.

- Burton, June K. Napoleon and the Woman Question; Discourses of the Other Sex in French Education, Medicine, and Medical Law 1799 – 1815. Texas Tech University Press; Texas; 2007.

- Campan, Madame. Edited by M. Maigne. The Private Journal of Madame Campan, comprising original anecdotes of the French court; selections from the correspondence, thoughts on education, etc. etc. Nabu Public Domain Reprints of the book published by Abraham Small; Philadelphia; 1825.

- Capellanus, Andreas. The Art of Courtly Love. Columbia Univ. Press; NY; 1960.

- Carlton, W.N.C. Pauline, Favorite Sister of Napoleon.

- Catinat, Maurice. Hortense chez Madame Campan (1795 – 1801), d’après des lettres inédites. Souvenir napoléonien; Paris; 1993.

- —. Madame Campan ou l’éducation des nouvelles élites. An article in Napoléon 1er, #17. Napoléon 1er; France; Nov/Dec 2002.

- Chevallier, Bernard. Malmaison en dates et en chiffres.

- —. Vues du château et du parc de Malmaison. Perrin; Paris.

- Clark, Anna. Desire; A History of European Sexuality. Routledge; NY & London; 2008.

- Connelly, Owen. The Gentle Bonaparte.

- Decker, Ronald; Depaulis, Thierry; Dummett, Michael. A Wicked Pack of Cards; The Origins of the Occult Tarot. Duckworth; London; 2002.

- Delage, Irène, and Chantal Prevot. Atlas de Paris au Temps de Napoleon. Parigramme; Paris; 2014.

- Desan, Suzanne. The Family on Trial in Revolutionary France. Univ. of Calif. Press; Berkeley; 2006.

- Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. A Reader’s Companion; Annotated Edition, With 780 Notes. Preface, Annotations, & Appendices by Susanne Alleyn. Spyderwort Press; Albany, NY; 2014.

- Ducrest, C. Mémoires sur L’Impératrice Joséphine; La Cour de Navarre & La Malmaison. Modern-Collection; Paris.

- Duthuron, Gaston. La Révolution 1789-1799. Librairie Arthème Fayard; Paris; 1954.

- Dwyer, Philip. Citizen Emperor; Napoleon in Power 1799-1815. Bloomsbury; London; 2013.

- Eveleigh, David J. Privies and Water Closets. Shire Publications; UK; 2011.

- Fain, Baron. Napoleon: How He Did It. Foreword by Jean Tulard. Proctor Jones Publishing Co.; SF, USA; 1998.

- Feydeau, Elisabeth de. A Scented Palace; the Secret History of Marie Antoinette’s Perfumer. Translated by Jane Lizop. I.B. Tauris; London; 2006.

- Fierro, Alfred. Dictionnaire du Paris disparu. Parigramme; 1998; Paris.

- Flandrin, Jean-Louis. Translated by Julie E. Johnson. Arranging the Meal; A History of Table Service in France. Univ. of Calif. Press; Berkeley; 2007.

- Fullerton, Susannah. A Dance with Jane Austen; How a Novelist and Her Characters Went to a Ball. Frances Lincoln Ltd; London; 2012.

- Garros, Louis and Jean Tulard. Itinérire de Napoléon au jour le jour 1769-1821. Librairie Jules Tallandier; France; 1992.

- Germann, Jennifer. Tracing Marie-Eléonore Godefroid; Women’s Artistic Networks in Early Nineteenth-Century Paris. The Johns Hopkins University Press; place; 2012.

- Gershoy, Leo. The French Revolution and Napoleon. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York; 1964.

- Giovanangeli, Bernard. (Éditeur) Hortense de Beauharnais. Bernard Giovanangeli Éditeur; Paris; 2009.

- Girardin, Stanislas de. Mémoires. Paris; 1834.

- Goodman, Dena. Becoming a Woman in the Age of Letters. Cornell University Press; Ithaca and London; 2009.

- Gueniffey, Patrice. Bonaparte, 1769 – 1802. Trans. by Steven Rendall. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Mass. & London; 2015.

- Guerrini, Maurice. Napoleon and Paris; Thirty Years of History. Trans., abridged and edited by Margery Weiner. Walker and Company; New York; 1967.

- Haig, Diana Reid. The Letters of Napoleon to Josephine. Ravenhall Books; UK; 2004.

- Hibbert, Christopher. Napoleon: His Wives and Women. (On Google books.)

- Hickman, Peggy. A Jane Austen Household Book. David & Charles; London etc.; 1977.

- Hopkins, Tighe. The Women Napoleon Loved. Kessinger Pub Co; place; 2004.

- Hortense. The Memoirs of Queen Hortense. Edited by Jean Hanoteau. Trans. by Arthur K. Griggs. Vol I & II.

- Hubert, Gérard and Nicole Hubert. Châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois Préau. Ministère de la Culture; Paris; 1986.

- Hubert, Gérard. Malmaison. Trans. by C. de Chabannes. Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris 1989.

- Huggett, Jane, and Ninya Mikhaila. The Tudor Child; Clothing and Culture 1485 to 1625. Fat Goose Press; UK; 2013.

- Jacobs, Diane. Her Own Woman; The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. Simon & Schuster; NY; 2001.

- Joannis, Claudette. Josephine Imperatrice de la Mode; L’élégance sous l’Empire.

- Johnson, R. Brimley. Fanny Burney and the Burneys. Stanley Pau & Co. Ltd.; London; 1926.

- Katz, Marcus, and Tali Goodwin. Learning Lenormand; Traditional Fortune Telling for Modern Life. Llewellyn Publications; Woodbury, Minnesota; 2013.

- Knapton, Ernest John. Empress Josephine. Cabridge, Massachusetts, 1963. Harvard University Press.

- Le Normand, Mlle. M. A. The Historical and Secret Memoirs of the Empress Josephine. Jacob M. Howard, translator. H. S. Nichols. London. 1895. Vol. I and II. Originally published in France 1820.

- Lefébure, Amaury, and Bernard Chavallier. National Museum of the Châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau. Museum; Montgeron; 2013.

- Lofts, Norah. A Rose for Virtue. (A novel.) Doubleday; NY; 1971.

- Mali, Millicent S. Madame Campan: Educator of Women, Confidante of Queens. Univ. Press of America; Washington DC; 1979.

- Mangan, J.J. The King’s favour; Three eighteenth-century monarchs and the favourites who ruled them. St. Martin’s Press; NY; 1991.

- Mansel, Philip. The Eagle in Splendour; Napoleon I and His Court. George Philip; London; 1987

- Marchand, Louis-Joseph. In Napoleon’s Shadow. (Marchand’s memoirs.) Preface by Jean Tulard. Proctor Jones; SF, Calif.; 1998.

- Marsangy, L. Bonneville de. Mme Campan À Écouen. Champion; 1879.

- Martineau, Gilbert. Caroline Bonaparte; Princess Murat, Reine de Naples. Éditions France-Empire; Paris; 1991.

- Masson, Fredéric. Joséphine, impératrice et reine. Jean Boussod, Manzi, Joyant & C.; Paris; 1899. On Gallica.

- Masson, Frédéric. La Société sous le consulat. Flammarion.

- —. Mme Bonaparte (1796-1804). Deuxième Edition. Librairie Paul Ollendorff; Paris; 1920.

- —.Napoléon et sa famille. Vol. I (1769-1802) Librairie Paul Ollendorff; Paris; 1897.

- —. Napoléon et sa famille. Vol. VIII (1812-1813) Librairie Paul Ollendorff; Paris; 1907.

- Mayeur, Françoise. L’´education des filles en France au XIXiem siècle. Perrin; place; 2008.

- McCutcheon, Marc. The Writer’s Guide to Everyday Life in the 1800s. Writer’s Digest Books, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1993.

- McKee, Eric. Decorum of the Minuet, Delirium of the Waltz. Indiana Univ. Press; Bloomington & Indianapolis; 2012.

- McPhee. Living the French Revolution, 1789-1799. Palgrave Macmillan; NY; 2009.

- Millot, Michel. The school of Venus, or the ladies delight, Reduced into rules of Practice; Being the Translation of the French L’Escoles des filles ; in 2 Dialogues. 1680.

- Mills, Joshua W. Imitatio Techniques from Classical Rhetorical Pedagogy. (A thesis) Johns Hopkins University; Baltimore; May 2010.

- Montagu, Violette M. Eugène de Beauharnais; The Adopted Son of Napoleon. John Long, Limited; London; MCMXIII.

- —. The Celebrated Madame Campan. Bibliolife, but originally published by Eveleigh Nash; 1914; London.

- Montjouvent, Philippe de. Joséphine; Une impératrice de légendes. Timée Éditions; France; 2010.

- Oman, Carola. Napoleon’s Viceroy; Eugène de Beauharnais. Hodder and Stoughton; London; 1966.

- Osmond, Marion W. Jean Baptiste Isabey; The Fortunate Painter.

- Pannelier, Alexandrine. Hortense et Eugène de Beauharnais à Saint-Germain. from her souvenirs. Bulletin 1981, Société des Amis de Malmaison.

- Parkes, Mrs. William. Domestic Duties; or Instructions to Young Married Ladies on the management of their households, and the regulation of their conduct in the various relations and duties of Married Life. Pub; New York; 1829.

- Pawl, Ronals. Napoleon’s Mounted Chasseurs of the Imperial Guard.

- Pellapra, Emilie de, Comtesse de Brigode, Princess de Chimay. A Daughter of Napoleon; Memoirs of Emile de Pellapra, Comtesse de Brigode, Princess of Chimay. Introduction by Princess Bibesco. Preface by Frederic Masson. Translated by Katherine Miller. Charles Scribner’s Sons; New York; 1922.

- Pitt, Leonard. Promenades dans le Paris Disparu. Parigramme; place; 2002.

- Prod’homme, J.—G., and Frederick H. Martens. Napoleon, Music and Musicians. The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp 579-605, Oct. 1921.

- Reichardt, J. -F. Un Hiver a Paris sous le Consulat. (1802-1803). Librairie Plox E. Plon; Paris; 1896.

- Reval, Gabrielle. Madame Campan, Assistante de Napoléon. Albin Michel; Paris.

- Richardson, Samuel. Letters written to and for particular friends, on the most important occasions. Directing not only the requisite style and forms to be observed in writing familiar letters; but how to think and act justly and prudently. (reprint by Gale ECCO Print Editions); originally London; originally 1741.

- Robiquet, Jean. Daily Life in France Under Napoleon.

- —. Daily Life in the French Revolution. James Kirkup, trans. The Macmillan Co. New York, 1965.

- Rogers, Rebecca. From the Salon to the Schoolroom, Educating Bourgeois Girls in Nineteenth-Century France. Penn State Univ. Press; Univ. Park, Penn.; 2005.

- Saint-Amand, Imbert de. The Wife of the First Consul. Trans. by T. S. Perry. Scribner’s; NY; 1890.

- Sand, George. Lettres d’un Voyageur. Penguin; Englan; 1987 (from original 1837).

- Savine, Albert. Les Jours de la Malmaison. Louis-Michaud; Paris; 1909.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens, A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, 1989. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Schlogel, Gilbert. Émilie de Lavalette; Une légende blessée. France Loisirs; Paris; 1999.

- Seward, Desmond. Napoleon’s Family. Viking; New York; 1986.

- Shields, Carol. Jane Austen. A Penguin Life. A Lipper/Viking Book; NY; 2001.

- Steinbach, Sylvie. The Secrets of the Lenormand Oracle. Self-published; na; 2007.

- Stuart, Andrea. The Rose of Martinique; a life of Napoleon’s Josephine.

- Sullivan, Margaret C. The Jane Austen Handbook. Quirk books; Philadephia; 2007.

- Tour, Jean de la. Duroc (1772-1813). Nouveau Monde Editions; Paris; 2004.

- Turquan, Joseph. The Sisters of Napoleon; Elisa, Pauline and Caroline Bonaparte After The Testimony of Their Contemporaries. Isha Books; India; 1908 (2013).

- Warner, Sylvia Townsend. Jane Austen. Longman Group Ltd.; 1964; 1970.

- Weiner, Margery. The Parvenu Princesses. William Morrow & Co; NY; 1964.

- Whatman, Susanna. The Housekeeping Book of Susanna Whatman (1776-1800). Century; London; 1987. Originally published in 1776.

- Whitcomb, Edward A. Napoleon’s Diplomatic Service. Duke University Press; Durham, N.C.; 1979.

- Williams, Kate. Josephine; Desire, Ambition, Napoleon. Hutchinson; London; 2013.

- Winegarten, Renee. Germaine de Staël & Benjamin Constant; A Dual Biography. York University Press; New Haven and London;2008.

- Wright, Constance. Daughter to Napoleon; a biography of Hortense, Queen of Holland. Holt, Rinehart and Winston; NY; 1961.

{Photo above by Giammarco Boscaro on Unsplash.}

by Sandra Gulland | Dec 2, 2015 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Game of Hope, The Josephine B. Trilogy |

Tracking down facts can be a time-crunching task … but a very enjoyable one when the goal is in sight.

I began with a simple question: Where was Hortense’s father executed and buried? I think these were things she might have wanted to know.

Portrait of Josephine and her two children, Hortense and Eugène, visiting their father in prison.

False leads

In the process, I found many wrong answers … which reinforces the common knowledge that the Net can’t be trusted. However, I knew enough to know when the answer was wrong, and kept looking.

In the process I ended up making a correction to a Wikipedia page … which rather thrilled me. Alexandre was defined, simply, as the lover of Princess Amalie of Salm-Kyrburg, a friend of Josephine’s who secretly acquired the land after the Revolution because her brother is buried there. Not only was it curious that Josephine and their children were not mentioned, but I very much doubt that Alexandre was Amalie’s lover. Other women, certainly, but not Amalie.

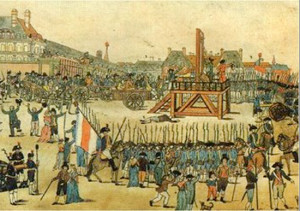

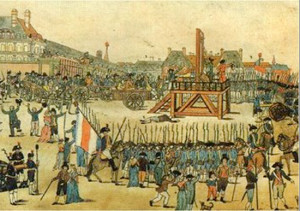

Place du Trône-Renversé—now Place de la Nation—where Hortense’s father was guillotined.

Alexandre was guillotined not in the Place de la Révolution (Place de la Concorde now) or Place de Grève (in front of the l’Hôtel-de-Ville), as if often claimed, but in Place du Trône-Renversé (now Place de la Nation), on the western edge of Paris. Apparently the other execution sites had become so bloody they had to find a new spot.

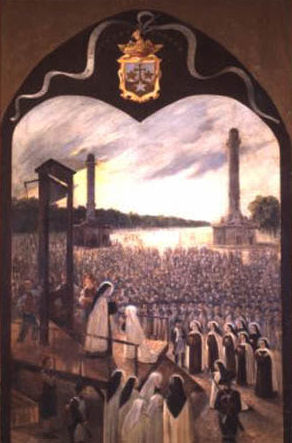

Mass executions at the height of the Terror

In a matter of about 6 weeks (from June 13 to July 27, 1794) 1306 men and women were guillotined, as many as 55 people a day. I imagine that it was hard work keeping the blade sufficiently sharp.

How to dispose of all the bodies?

It was also hard work disposing of the bodies. What is now the Picpus Cemetery was then land seized from a convent during the Revolution, conveniently close to Place du Trône-Renversé. A pit was dug at the end of the garden, and when that filled up, a second was dug. The bodies of all 1306 of the men and women executed in Place du Trône-Renversé were thrown into the common pits including 108 nobles, 136 monastics, and 579 commoners … .

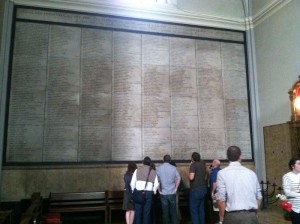

The mass graves are simply marked.

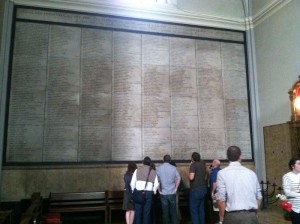

One of two wall listing the names and ages of the dead.

Le Cimetière de Picpus today.

Of those executed, 197 were women, including 16 Carmelite nuns, who went to the scaffold singing hymns.

In all the research I’ve done in Paris over the decades, I’ve yet to go to either the Place du Trône-Renversé (Place de la Nation) or the Picpus Cemetery. I believe I’m due.