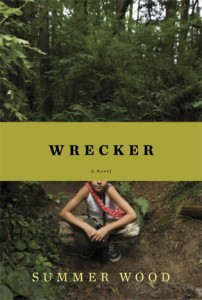

Not long ago I posted a “shout out” book review of Wrecker by Summer Wood. (Read my blog post here.) I read the novel on the Kindle app on my iPad, but the novel moved me so much I just ordered a print edition so that I could share it with my friends.

I also contacted the author: would she mind answering a few questions about craft? She very kindly consented. I found her answers to the questions both instructive and inspiring, and I think you might, too.

You are obviously a writer who takes craft very seriously. Could you tell us about your process? Do you outline? How do you go about revising? Do you use readers?

The most important part of my process is, in a way, the least serious: I allow myself plenty of time to play. I start every writing session with a free-write. And I’ll stick with it for as long as I feel the need – which may be for the whole session, even. It’s not about lacking discipline; it stems from a deep belief that I can’t push a story or a chapter or a book to completion, I can only work with the energy that arises naturally from it. And I tap that energy by fooling around with words, seeing where they lead me. Almost always they lead me to story.

This could sound like a frivolous approach, but, honestly, I’m very blue-collar about writing. When I’m working on a novel or a story (which is to say, when I’ve dedicated that time in my life to make composition the central activity), I pack a lunch and I get to work. I don’t let other things intrude on that time; I unplug the modem (literally!), and a lot of times I don’t answer the phone. I’ve figured out the things that work for me and I try to maximize the time I have to write.

Do I outline? Only once I’m far enough along in a project to feel like I really know what’s going on. Even then, I have no allegiance to it. Generally speaking, I think outlines work best with novels that derive most of their energy from plot; they can be indispensable, then. My work is very carefully structured, but rarely is plot the most significant element of that structure. So – no, not much outlining in advance, although lots of story architecture in process.

Revision is a huge part of my process. The free-writing helps make clear to me what’s most vital to the story I’m telling, and that may take a while. I have to cull through lots of language to identify the energy patterns in a particular story or chapter – or even whole novel, because, while I do revise considerably as I go along (so, you know, I can stand to read it over!), I don’t know until I’m at the end of a draft how the whole thing will fit together. And then I go back over it, and over it, and over it again before I think about showing it to anyone.

It’s clear, in Wrecker, that you love every character. They are so flawed, yet deserving of love. In your author’s note, you said something about your editor helping you to love every character. Could you tell us what that involved?

Which character did you find the most challenging?

I can answer both questions in a single response: my agent, Dan Conaway, helped me grow to love Willow. She was by far the most difficult for me because she’s just so competent – and reserved. Her reserve extends even to the diction of the chapters written from her point of view. She has tremendous clarity but a kind of a narrow perspective, and she guards her own secrets with her slightly-frosty elegance. I knew Willow was important to the story but, honestly, I didn’t really like hanging out with her.

But Len really likes hanging out with her, and Dan was drawn to that evolving love story, and urged me to go further with it, to reveal more about them both. What I found was that when I looked at Willow through Len’s eyes, I could see the things that were really wonderful about her. They have nothing to do with her competence. They have to do with her inner struggle, her awareness of and at the same time resistance to acknowledging her own flaws and failures. She doesn’t actually see how great she is – but Len does, and so do Melody and Ruth, who find it so much easier to forgive than she does. Seeing her through their eyes, and watching her stumble awkwardly toward trying to help Wrecker, softened my own impression of her – and so did her growing romantic involvement with Len.

You’ve mentioned that Ruthie is an emotional touchstone in the novel. With so much going on that’s in flux, it was wonderful having Ruthie there, a woman of such big heart, a woman without any hesitation about loving. How wonderful, too, that there was always something wonderful cooking. Are any of your characters drawn from your life?

Yes and no. Sorry! But it’s complicated, really. I mean, of course my life experience will lend ideas and spark connections; but once a character arises on the page her whole being has to have integrity, wholeness, and you can’t do that by patching together miscellaneous details from models. Well, some writers can, I guess – but, for me, I often won’t snap to the ways that a character reflects aspects of real-life people I know until someone points out the similarities to me. So it’s a very subconscious process. Ruth, of all the characters in Wrecker, is closest in character to a couple of people I know. She’s very different from them in detail and circumstance, but that particular quality she has – big-hearted but not sappy – she does remind me of them. I like that. And the cooking? Can you guess that I love to eat?

You’ve talked very movingly about mothering, and especially about your experience taking four young foster children into your home and heart. To quote: “I wrote WRECKER because I guess I can’t let go. You never really let go of the people you love, do you? You send them off, you wish them well, you let them be, but you go on carrying some part of them with you until the day you die.”

I think this is one of the strongest emotional pulls of the novel, what one might call “the mother force”—but in your novel, this force isn’t only in women, but in men, as well. I was extremely moved by the tenderness with which Len “mothers” his brain-injured wife, for example. Did you know from the beginning that this would be an important theme in your novel, or did you discover it though many drafts?

Ah, gosh. No. I don’t really know where I’m going when I start a novel; I’m just taken with characters, and place, and things that happen, and relationships. Sometimes I don’t know until I’m done – I mean, really done – and somebody else tells me what the book is about. Weird, huh? But I think it’s not uncommon for writers to be kind of blind to the themes of their work. In a way, writing for me is excavation: uncovering the things that matter to me, revealing their outlines, exploring their details. It’s more about asking the questions than about promoting a particular point of view or expressing a theme. For me, the theme has to grow naturally from the story, rather than the other way around.

That said, I would certainly agree to a degree of obsession around the whole question of mothering, nurturing, all that. In a broad sense, I’m intrigued by the mistakes we make as we stumble around in love. I never get tired of looking at love. And parenting is such a rich vein in that broader ore, isn’t it? Parenting is rife with potential for failure. Not just potential, but, really, likelihood; I mean, who among us is ever as good a mother as she would like to be? And still we throw ourselves into it. We’re driven to love and to nurture the ones we love. Even as we make mistakes, fail them, fail ourselves. But it’s not the failure that interests me. It’s that we keep rising, again and again, to the need.

What authors inspire you?

I go back, over and over, to Flannery O’Connor’s stories. She amazes me. And I love poetry: Ovid (Metamorphoses, in the Ted Hughes translation), Mary Oliver, Jack Gilbert, James Merrill (The Changing Light at Sandover), lots of others. Place, both in literature and in actual fact, inspires me. There’s a terrific book called Home Ground, edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney. It’s a lexicon of regional terms for landscape features, and I’m zealous about recommending this. Janet Kauffman is a writer who can combine electric language with breathtaking (often very funny) stories set firmly in place. I think she’s a tremendous writer, and underappreciated. Grace Paley – I still miss her, can’t believe we won’t get any more stories from her. Melville. Barb Johnson, whose first book of stories, More of this World or Maybe Another, came out in 2009. I should stop now, but it’s hard to do!

Thank you so much, Summer. There are many things you said that resonate with me. The idea of looking at a character through another character’s eyes, for one, the importance of play. I’ve ordered books by a number of the authors you recommend. (I still miss Grace Paley, too.)

For readers here, I urge, urge, urge you to read Wrecker. It’s a rare and beautiful novel. You will not be disappointed.

{Photo of Summer Wood by Miriam Berkley.}