by Sandra Gulland | Apr 8, 2017 | Baroque Explorations |

I have been doing quite a bit of research into Phantasmagorie for the Young Adult novel I’m writing about Josephine’s daughter Hortense.

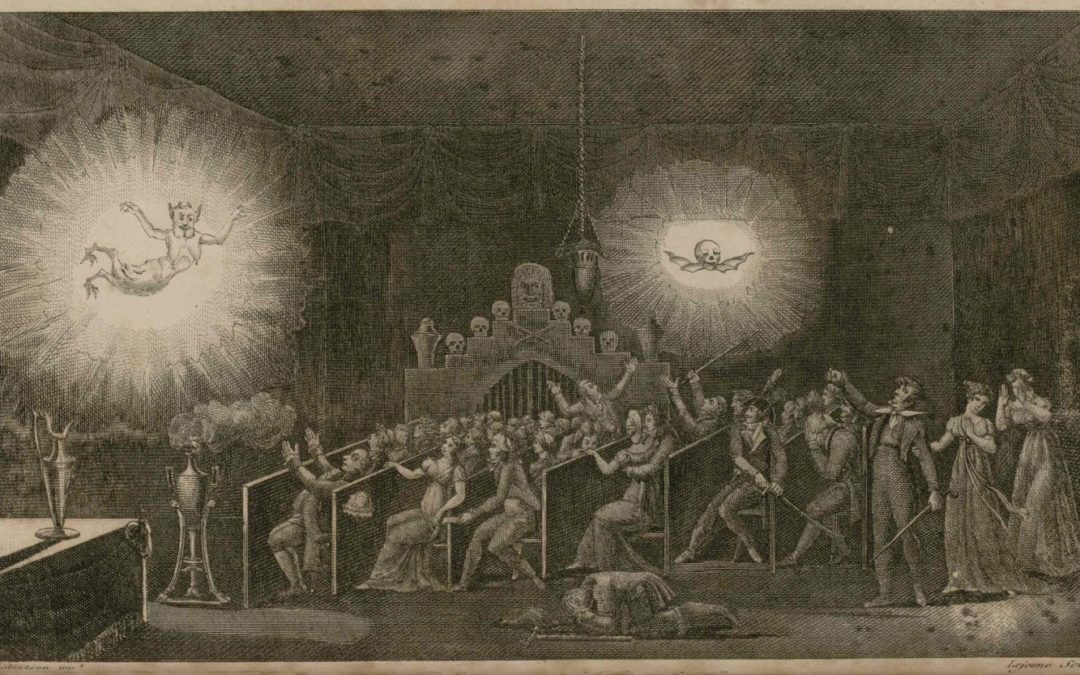

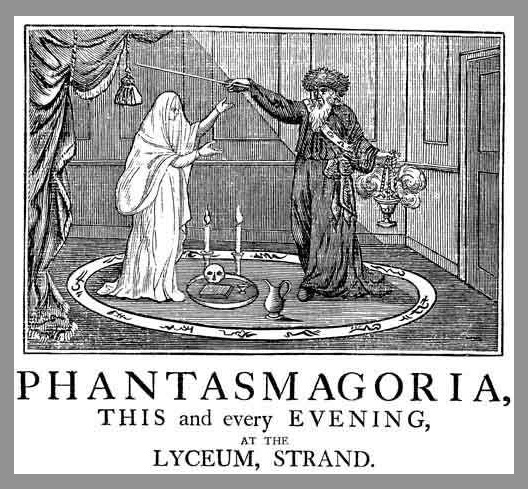

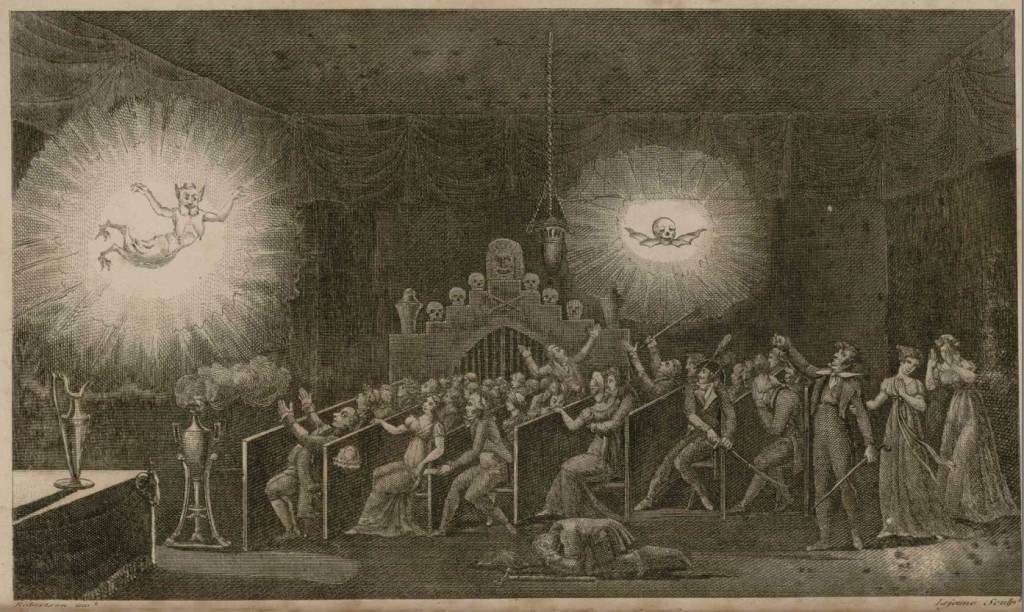

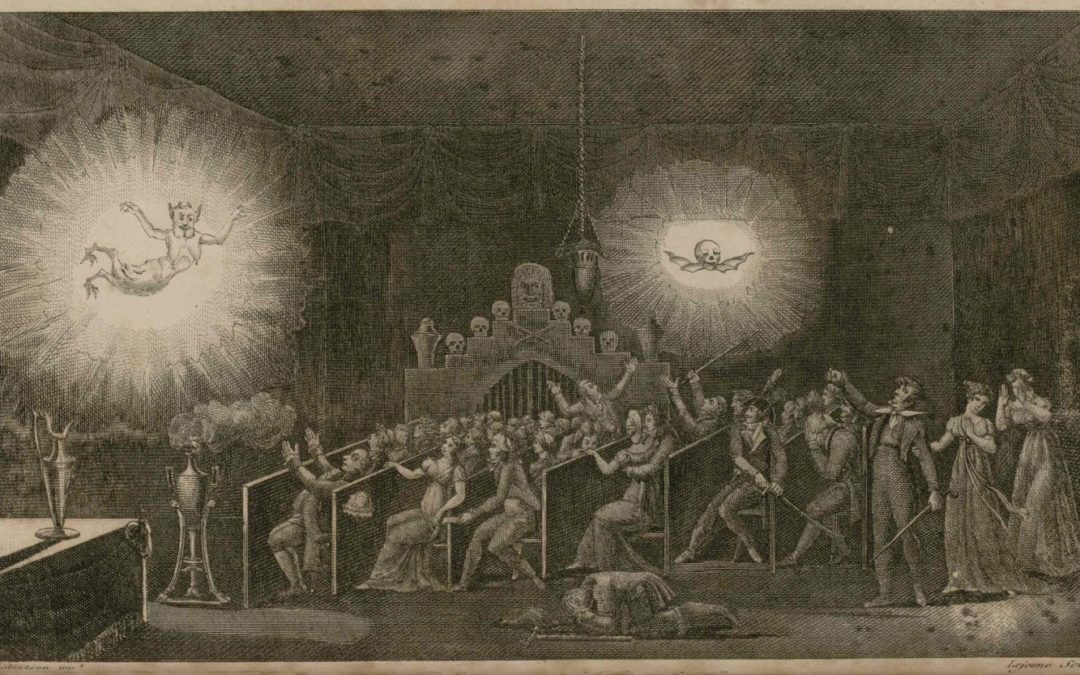

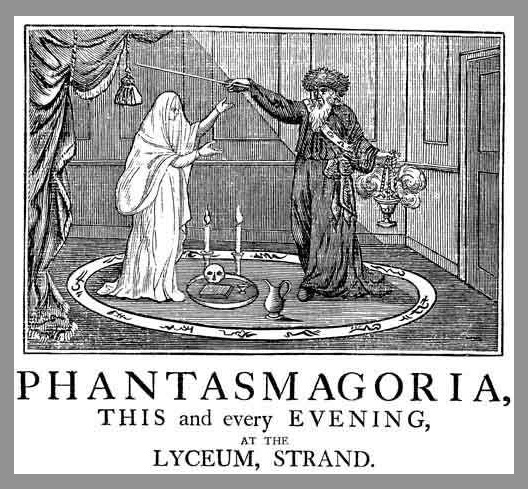

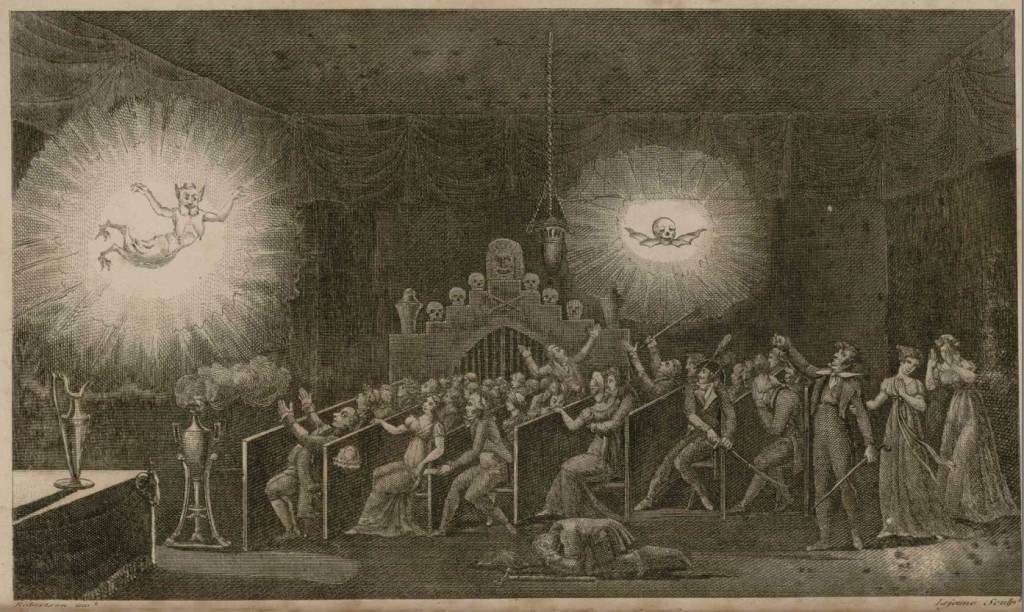

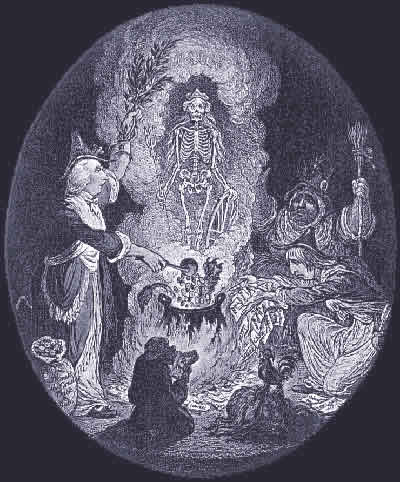

Phantasmagoria was an extremely popular “show” put on for both children and adults in France after the French Revolution, featuring the appearance of ghouls, ghosts, spectres and apparitions.

It was shown in other countries of Europe, but it was by far most popular in France, where so many had lost loved ones during the Terror, and where, apparently, a hunger for contact with the afterlife was strong.

Etienne-Gaspard Robertson (1763 – 1837) was the mastermind behind these productions. His first French exhibition of “Fantasmagorie” was at the Pavillon de l’Echiquier in Paris. He later staged it in the abandoned chapel of a Capuchin monastery near the Palace Vendome.

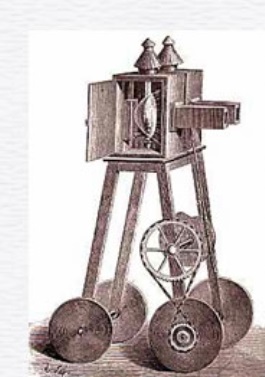

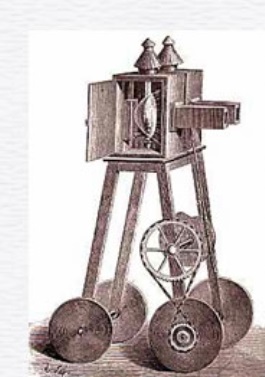

Robertson devised a double-lens lantern on wheels to create his ghostly effect, an invention which is considered the predecessor of the motion-picture camera. (In 1799 he got a patent for this camera, calling it a Fantoscope.)

To create the shadow play, Robertson used smoke, huge sheets of glass, mirrors, and several mobile lanterns. He would project from below the stage, and the hidden movement of a lantern created the illusion of motion. He would change the position of the lens to show a figure growing larger (and apparently closer), yet remaining in sharp focus. He also used rear projection, and projection onto gauze coated with wax, ironed to give a translucent appearance.

The purpose of the show was to terrify the audience—and it succeeded. It could well be considered the forefather of today’s horror movie.

Much of this information is from The History of the Discovery of Cinematography by Paul Burns, which unfortunately is not available on-line at this time.

For excellent documents, see The Richard Balzer Collection.

For a bibliography of books related to the history of cinematography, click this link.

For a full programme: Fantasmagorie de Robertson, Cour des Capucines, près la place Vendôme.

Robertson describes some of his phantasmagoria in his Mémoires.

(Phantasmagoria is not to be confused, by the way, with the 1995 interactive video game: Phantasmagoria!)

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Feb 21, 2015 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Resources for Writers, The Writing Process |

When I get stuck for a simile or metaphor, I sometimes rummage around on Books Google.

Eyes like … ?

What would someone in the 17th or 18th century have said?

Eyes like fish pools.

Not exactly what I was looking for!

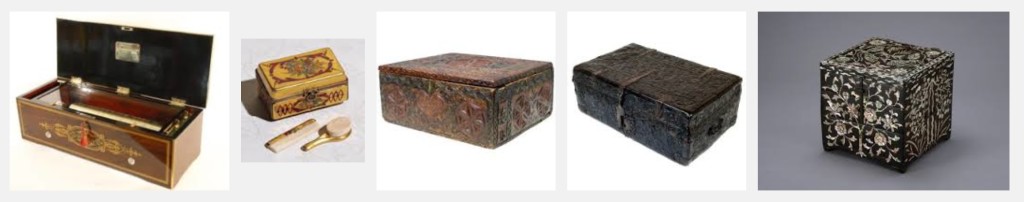

Eyes like a comb-box.

I admit: this one intrigued me. What is a comb-box? A quick Google search for “18th century comb-box” revealed a wealth of them.

But nothing whatsoever like “eyes,” however.

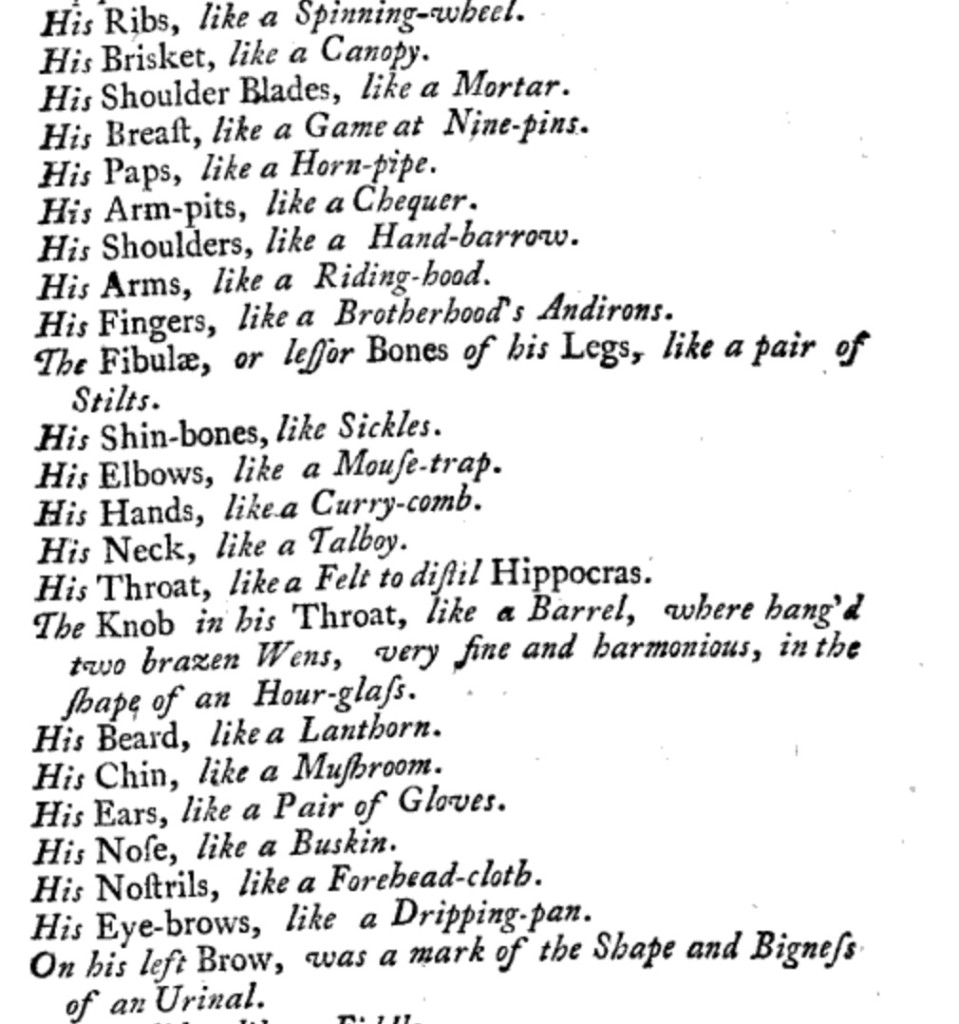

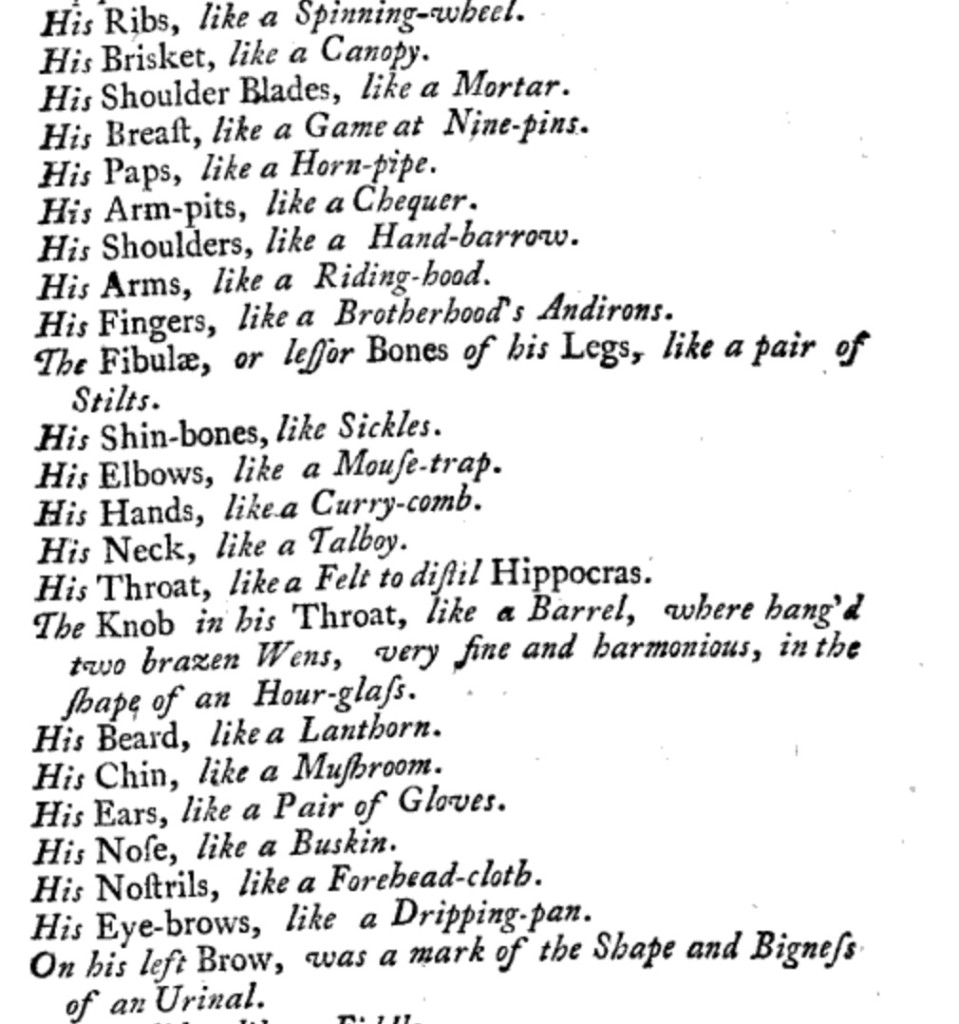

Intrigued, I followed the link and discovered The Works of Francis Rabelais, published in 1738. Chapter XXX is a long list of nonsensical (at least to me) similes:

The nape of the neck like a paper lantern.

Spittle like a shuttle.

The bridge of his nose like a wheel-barrow.

The windpipe like an oyster-knife.

This one is perfect, however:

Hair like a scrubbing-brush.

Of course all this led to an exploration of what Rabelais was getting at (an anti-Catholic spoof of sorts), which only goes to prove how diverting procrastination can be.

Now, as for those eyes …

For those of you who would like specific steps in using Books Google for this type of search:

Go to https://books.google.com

Type in a word or phrase. Click “Search books.”

On the page that comes up, click “Search tools.”

Then click “Any time” and a menu will drop down.

Click “Custom range.” Enter your range and click “GO.”

by Sandra Gulland | Nov 21, 2014 | Baroque Explorations |

It’s simply astonishing what one can now find on-line. In the way of any wander through library stacks, I came upon this title on Gallica.bnf.fr, the French national library on-line:

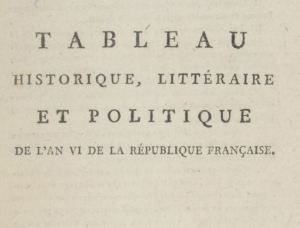

Tableau historique, littéraire et politique de l’an VI de la Républic française.

Of course it was not at all what I was looking for, but although “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometime, you find you get what you need.” :-)

I love the way the digital book opens with its cover:

And then turns to the marbled end-paper:

Here’s a crop of the title page:

(You can almost feel the rich texture of the paper.)

And then, the first chapter division:

What caught my attention “leafing” through this book was the section on legislation, a daily account of laws passed in the years 1798-1799.

They are very detailed: they needed to be. The French government was (once again) creating a government from scratch. Laws mentioned cover passport regulations, import duties, the re-establishment of a national lottery, the legislateurs’ own schedule (they will no longer meet on décadis (the end of the 10-day week), patents, manufacture of goods, the “uniform” to be worn by the members of the legislature …

“…habit français, couleur bleu national, croisé et dépassant le genou. Ceinture de soie tricolore, avec des franges d’or. Manteau écarlate à la grecque, orné de broderie en laine. Bonnet de velours, portant une aigrette tricolore.” – page 142

Alas, I am unable to find an illustration of this costume. No doubt they were somewhat more circumspect than those from 1796. Below left, Executive Director from 1796, compared to Napoleon’s uniform of choice as First Consul on the right:

The legal record is many pages long, but I’ll note a few:

One law passed condemns to death those who rob by force or violence. This is significant because violent crime had become rampant.

Marriages (which must be civil) could only be held on décadis.

One significant law, passed 12 Nivose, an VIII (January 1, 1799), declares that Blacks born in Africa or in foreign colonies, and transferred to French islands, were free as soon as they step foot on French soil. The Revolutionary government had several years before outlawed slavery in France, but I don’t believe that it had gone so far as to declare it illegal in its colonies. (I should note that Napoleon will eventually reinstate slavery in the French colonies, and no: it was not Josephine’s doing.)

It’s delightful how worthwhile procrastinating can be. I found an excellent Revolutionary calendar (more on that later), learned the date when there was an eclipse of the moon, what the new national fêtes were to be, and much, much more.

by Sandra Gulland | Oct 18, 2014 | Baroque Explorations |

It continues to amaze me what one can find on-line now. I was searching for pre-1805 publications that contained the name Madame Campan, the founder and director of the highly esteemed boarding school Josephine’s daughter, Hortense de Beauharnais, went to.*

I was charmed to find Madame Campan’s name listed in this title:

At the beginning of the Mémoires is thank you note to the subscribers, a very long list which includes many members of the Court (including the King and Queen). I gather that all these people paid in advance in order for the Mémoires to be published. This reminded me immediately of our on-line crowdsourcing like Kickstarter.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

*I was on-line trying to find out the name of the school as it had been referred to at the time. Here are two possibilities:

L’Institut National des Jeunes Filles/National Institution for Young Women

I’ve also seen (but only in English): National Institution for the Education of Young Women.

l’Institut national de Saint-Germain/The National Institution of Saint-Germain

I have doubts about this name because during the Revolution the name of Saint-Germain-en-Laye had been changed to Montagne-Bon-Air. It was changed back 28 février 1795, but would Madame Campan have been so bold as to jump immediately on the reversal?

by Sandra Gulland | Sep 14, 2014 | Baroque Explorations |

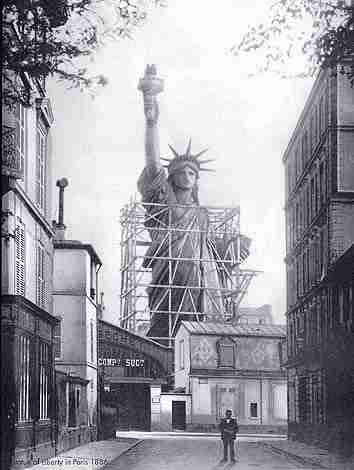

I began this essay on the Statue of Liberty October 28, 2012—which, coincidentally, happened to be the statue’s 126th birthday. It was also the day the statue was scheduled to reopen after renovations. Days later, Hurricane Sandy hit New York, and two images were often seen on the Net. They aren’t authentic images, in fact, but they poetically capture a greater truth—the image of endurance in the face of tremendous challenge.

Endurance in the face of challenge was what it took to create the statue, in fact. It’s a fascinating and inspiring history, demonstrating how a few persistent individuals can effect great change.

How does the Statue of Liberty survive a storm?

Although the storm did damage Liberty and Ellis Islands, there was no damage to the statue. How did Lady Liberty survive? The key is in how she was designed—by Monsieur Eiffel, creator of the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

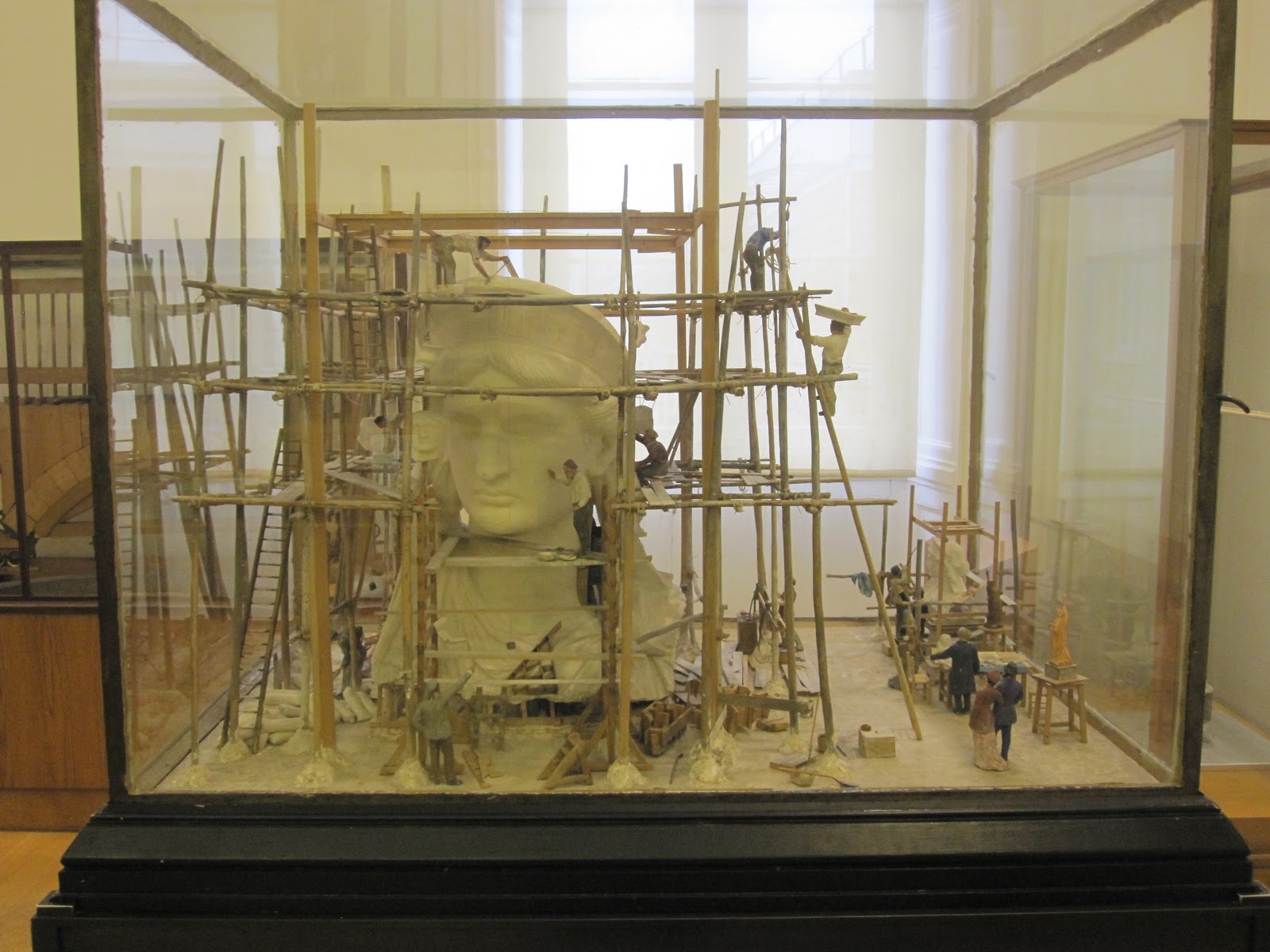

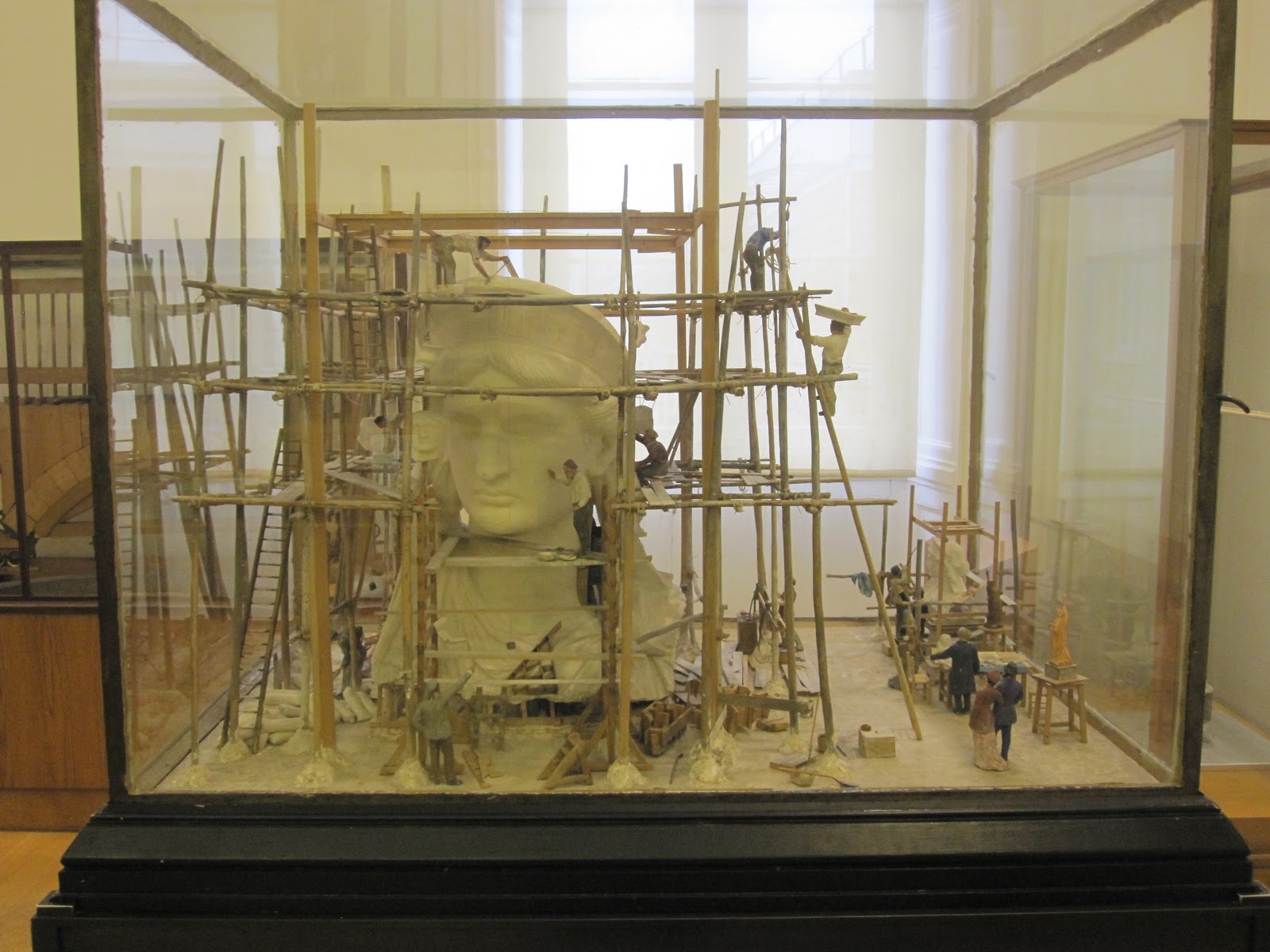

My fascination with Lady Liberty began in Paris, when my husband and I went to the Musée des arts et métiers. The museum is a wonderful display of the history of innovation, mostly from the 18th century. One thing that particularly struck me were the mock-ups of the work site of the Statue of Liberty being built.

(The face of the Statue of Liberty is touchingly modelled on that of the sculptor’s mother.)

The statue began as most great projects do: as a bright light of an idea in one person’s mind. Frédéric Bartholdi, a French sculptor, thought it would be a wonderful way to commemorate the centennial of the American Declaration of Independence. Happy Birthday, U.S.A.*

A wonderful idea, but a problematic gift

The project proceeded in an equally typical fashion: with great frustration and wrangling. Did America even want such a gift? Where would they put it? And more to the point, who would pay for it?

It was eventually agreed that the U.S. would build the pedestal, and France the statue. A huge sum of money was required, and on both sides of the ocean fees, fund-raisers, auctions, and lotteries were used to try to raise the needed funds.

Little by little, things were set in motion. Frédéric was commissioned, and wisely chose Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, designer of the Eiffel Tower, to design the support structure. Eiffel opted not to use a rigid structure, but instead loosely connected the support structure to the skin. It’s this flexibility what allows the statue to endure high winds.

Fund-raising for the pedestal lagged in America, however, and work was suspended. Other American cities, including Boston and Philadelphia, offered to pay in return for relocating it. Joseph Pulitzer (founder of the Pulitzer Prize), publisher of a New York newspaper, announced a drive to raise $100,000 (the equivalent of $2.3 million today) by pledging to print the name of every contributor in the paper, no matter how small the amount, along with the touching notes he received:

“A young girl alone in the world” donated “60 cents, the result of self denial.”

“Five cents as a poor office boy’s mite toward the Pedestal Fund.”

A group of children sent a dollar as “the money we saved to go to the circus with.”

A dollar given by a “lonely and very aged woman.”

A kindergarten class in Davenport, Iowa, mailed the World a gift of $1.35.

Donations flooded in and work on the pedestal was resumed.

The Statue of Liberty crosses the ocean

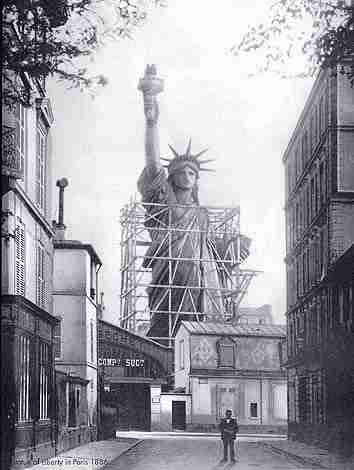

Once the pedestal was completed in America, Lady Liberty’s 350 pieces were packed into 214 crates and loaded onto the frigate “Isere.” It took four months to assemble her, and on October 28, 1886, she was officially “born” in a ceremony in front of thousands.![]()

On the morning of the dedication, a parade was held in New York City. As the parade passed the New York Stock Exchange, traders threw ticker tape from the windows—the first ticker-tape parade.

At the unveiling ceremony, creator Frédéric was called upon to speak, but refused. Was he too moved? It had taken over two decades of his persistent effort, and his dream had finally become a reality.

It’s such a wonderful story. After visiting that museum, I began to take notes for a possible children’s book on Lady Liberty’s amazing voyage.

* Lawyer and politician Édouard de Laboulaye was also an important part of the statue’s conception and creations, but for the purpose of this essay, I’ve focussed on Frédéric.

Painting above: Unveiling of the Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World by Edward Moran.