by Sandra Gulland | Dec 29, 2014 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

Last year, I posted a blog with almost this same name—Getting ready for 2014: resolutions on book-keeping and book-making.

I wrote:

We’ve made our resolutions, and one of mine is get to the bottom of the mail in-box three times in the year ahead. Wish me luck.

I’ve gotten fairly good about in-box zero; what I’m not that good at is actually dealing with the emails that I hide away in files with names like “URGENT” “FOLLOW-UP!”

Another resolution is to deliver The Game of Hope ahead of schedule (it’s due December 1). That will take more than luck: that will take constant perseverance!

Bravo! I did manage to do this, sending The Game of Hope to my publisher two days ahead of the due date.

I had other resolutions, of course: keeping my weight down, exercising, etc., which I kept fairly in-line. (I could have done better.)

What I did evolve this year—eventually—were two motivational systems for actually getting things done.

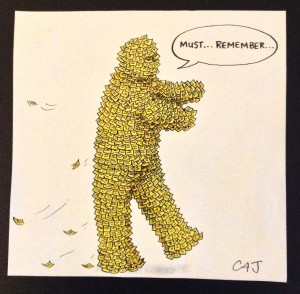

1: The Post-It method

- My To Do List for the day must fit on a post-it note (and not a big one).

- Each item should be measurable: i.e. “30 minutes, bookkeeping.”

- Tasks that are irksome should be introduced in 15-min. chunks. (I.e., said bookkeeping.)

2: The Jerry Seinfeld “Don’t Break the Chain” method

In conjunction with the daily post-it (as well as a more extensive compost-heap of long-term things to do), I’ve started using the Seinfeld method for the one daily task I resist most strongly: exercising. That I’ve finally found a way to actually overcome my resistance is a strong testimonial to the effectiveness of this method.

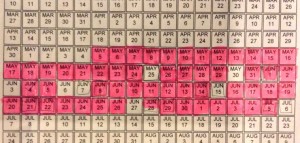

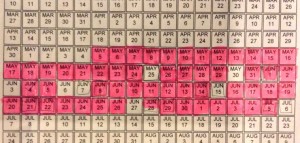

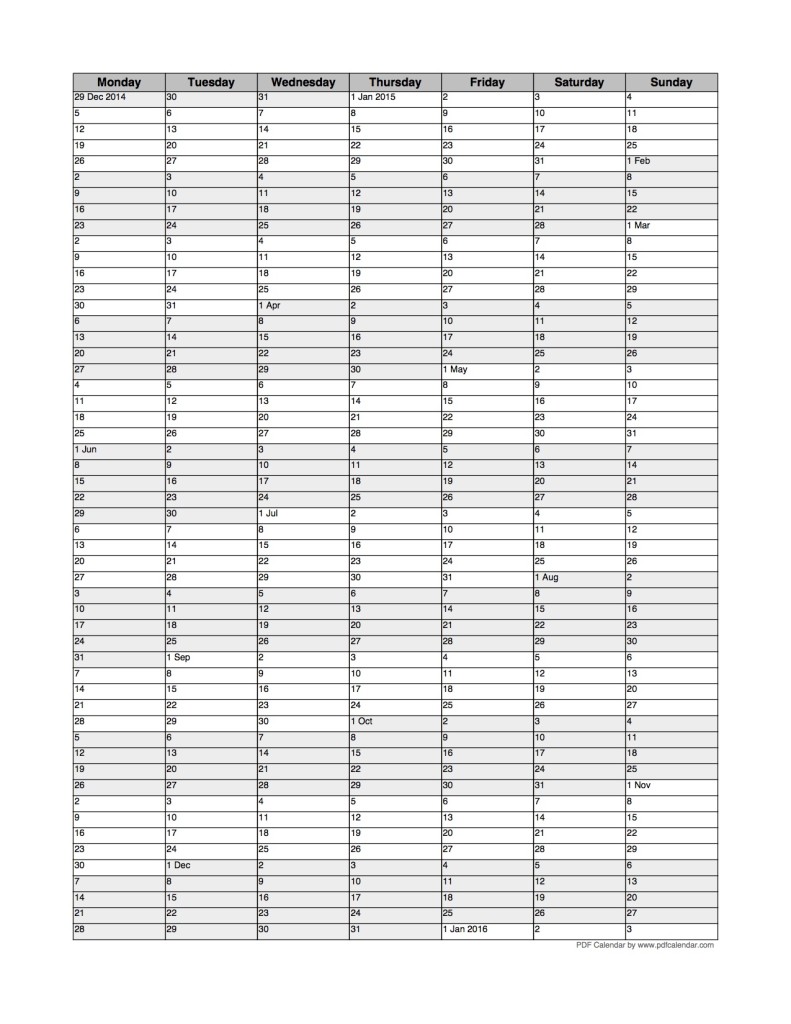

Here is a snap from my “Don’t Break the Chain” calendar earlier this year:

Every day I do what I’ve promised (30 minutes on the treadmill, in this instance), I colour in the date. The idea is not to have any gaps—and the visual reminder, for me, is strong.

Seinfeld originally suggested this system for writing. (I wrote about using the Seinfeld “Don’t Break the Chain” method in another blog post: A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, word?) I highly recommend this system if you want to write very day: just make sure that the daily goal you set isn’t overly ambitious. It’s better to write for 30 minutes a day every day, than to attempt 2 hours a day and fail.

“Don’t Break the Chain” calendars

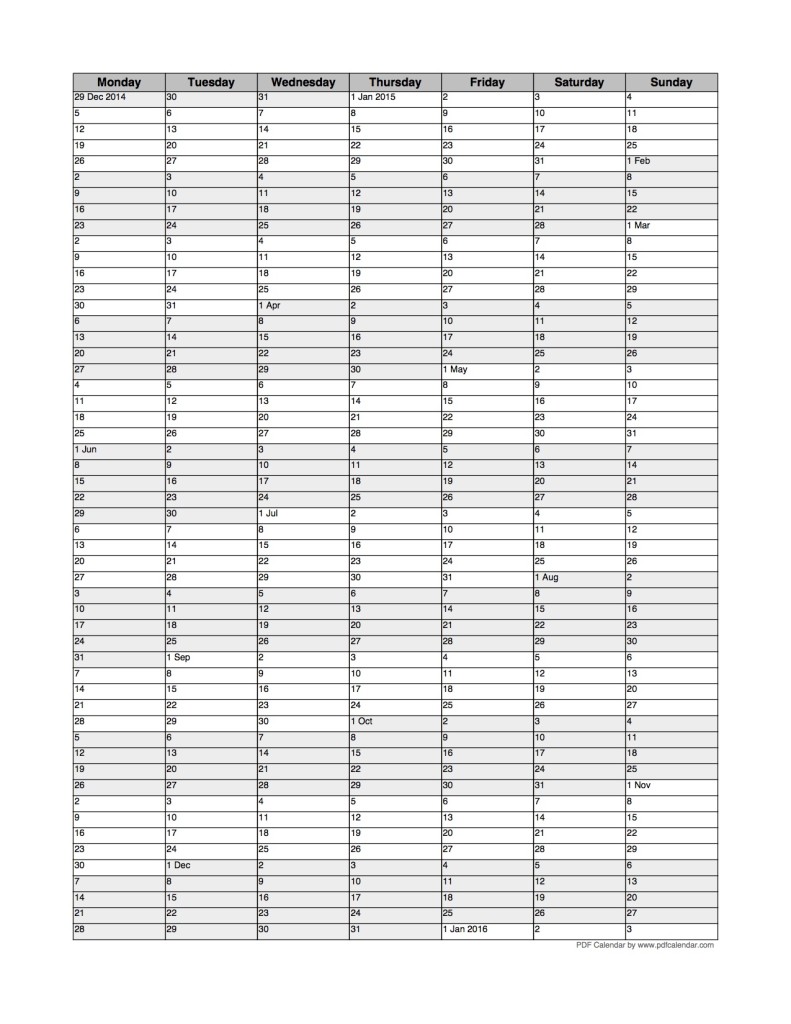

If you’re going to use the Seinfeld method, you need to print out a continuous calendar. Click to download a printable version of this one I created using PDFCalendar.com:

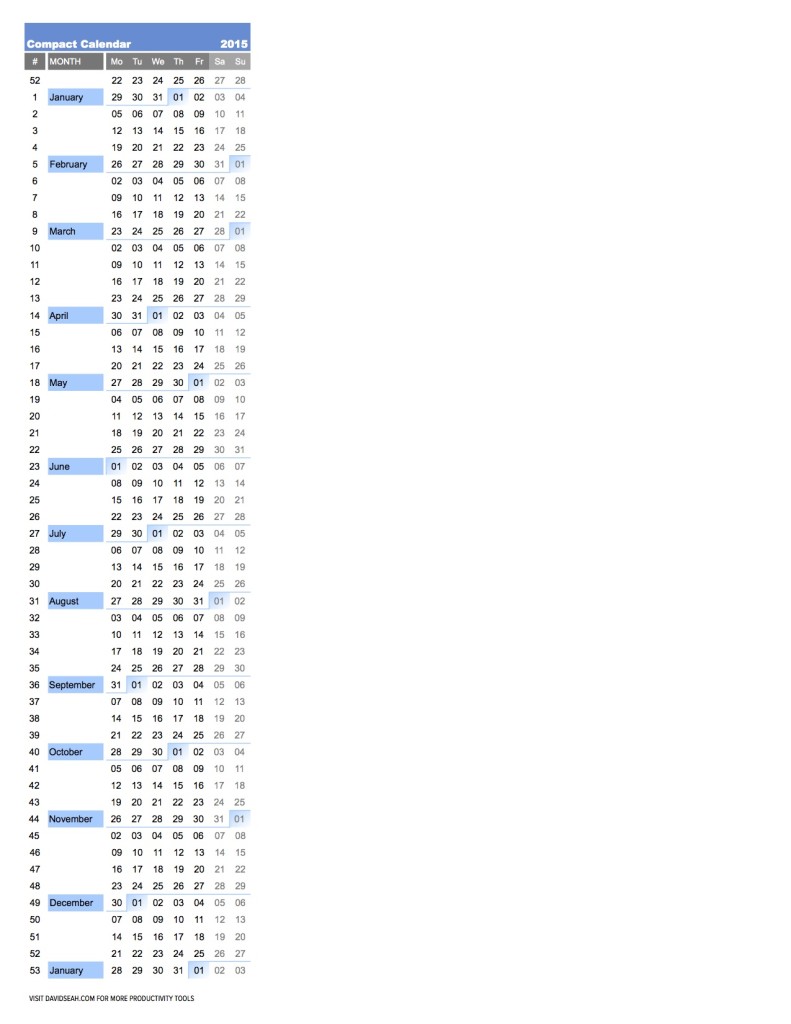

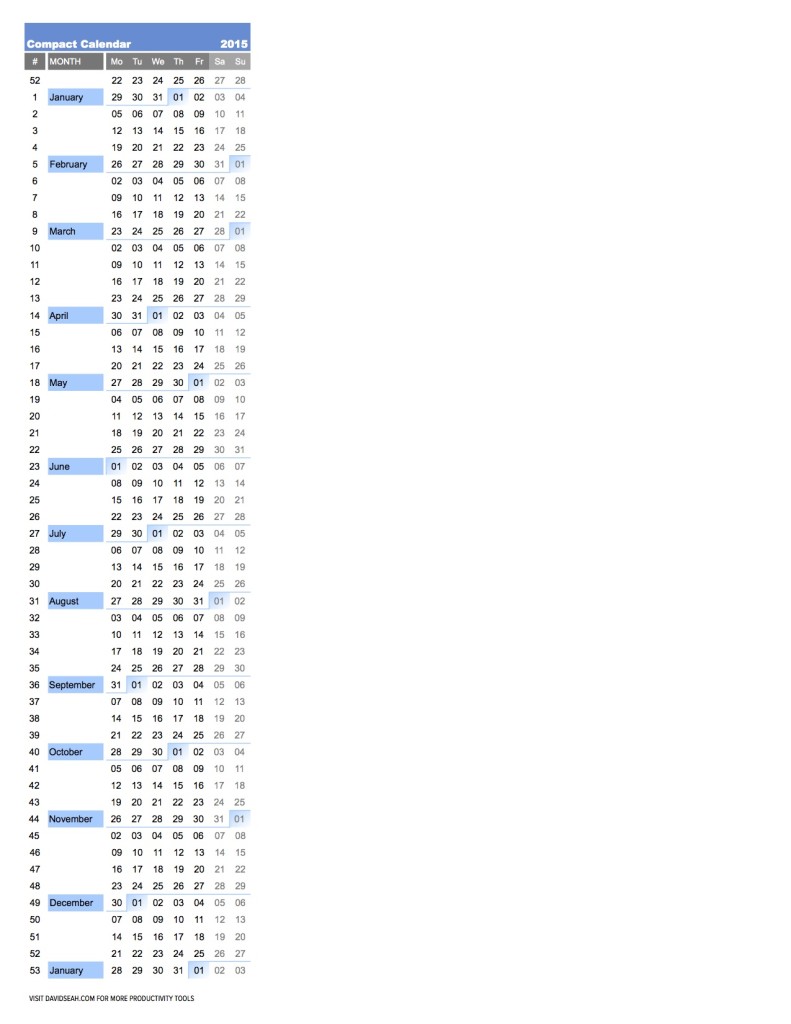

Another continuous calendar created by David Seah allows you to make notes:

The Writer’s Store also offers a calendar to print out: here.

I have a system when it comes to writing a draft: I set a goal of about about 1000 words a day and record my progress in a small Moleskine diary. If you are casting about for a way to keep track, consider this Word Tracking Calendar, also by David Seah.

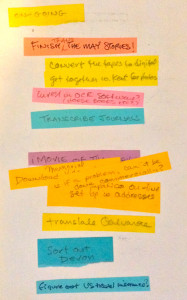

I was amused to find these very old To Do Lists of mine:

![]()

![]()

The colours were random—they did not signify anything. Note the To Do: “figure out the fax machine.” I never did manage that!

My resolutions this year? To finish The Game of Hope and write a solid first draft of The Princess Problem (the working title of the second Young Adult about Hortense). Also: keep up with daily exercise.

And, of course: in-box zero—but without simply filing away the emails to be answered.

by Sandra Gulland | Oct 14, 2014 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

A reader asks:

“I’ve written my second novel and I just can’t seem to get it to the next step. I’m stuck in the querying process and it is quite the daunting process indeed.”

Daunting: yes.

Perseverance is key

Perseverance is the key to succeeding as a writer:

- perseverance in continually learning about the craft,

- perseverance in not being discouraged by rejection (and even learning from it),

- perseverance in never giving up.

All of your questions (and more) will be answered in this excellent YouTube video interview by John Truby.

John Truby is a screenwriter, director and teacher of screenwriting. He has a very great deal to offer on the craft of story, so centrally important to novels as well as film.

In terms of plot craft, Truby’s book, Anatomy of Story, is excellent, but an even better book—at least to begin with, I think—is Save the Cat, by Blake Snyder. It is short and to-the-point.

Study the craft, revise, persevere.

(While you are waiting for responses to your second novel, you are working on your third novel: right?)

For more in this Writer’s Routine series:

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

A writer’s routine: pantster or plotter?

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative head space

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

A writer’s routine: where to write

A writer’s routine: on resisting an outline

A writer’s routine: how to be productive

A writer’s routine: on hunting & gathering

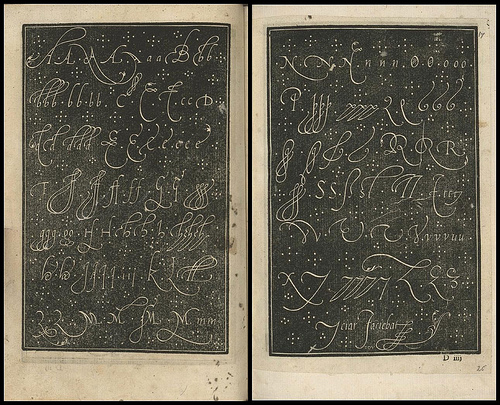

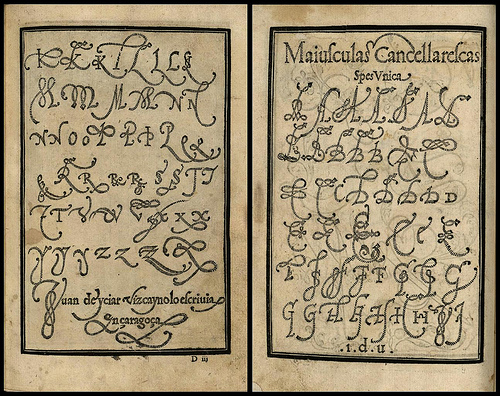

Image at the top from “A Most Delicate Art” at BibliOdyssey.

by Sandra Gulland | Oct 6, 2014 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

A friend asks:

When you are reading recreationally do you take notes if something triggers an idea for your latest work?

There is a part of the creation process I call “hunting and gathering.” This is most often when you’re fully immersed, looking for solutions, and ideas seem to come from everywhere. I’ve learned to always have note paper and a pencil on hand.

Or, do you try to turn your “work brain” off when reading recreationally?

By the same token, I need to wind down in the evening, so while I might jot down a note, I do not read for research, and draw the line at having a high-lighter in hand. (Yes, I mark up books.)

If you are driving in the car, out on a walk, or anywhere other than your desk and an idea comes to you (which would be great for your work), what is your process for remembering it? Dictaphone, notepad?

For note-taking while walking, nothing beats a scrap of paper and pen in a back pocket, but taking notes while exercising — on a treadmill, for example — can be tricky. Also, I’ve not yet found a good way to take notes while driving. I do keep a post-it pad stuck to the dash and a pencil handy, but it’s a bit dangerous if I can’t pull over.

Some writers use a dictaphone, and I’ve gone to some trouble to learn to use one, but I’m not very good at keeping it charged or playing back the notes. (I’m working on this.)

There are, of course, apps for just about all of this: apps for dictation, for note-taking.

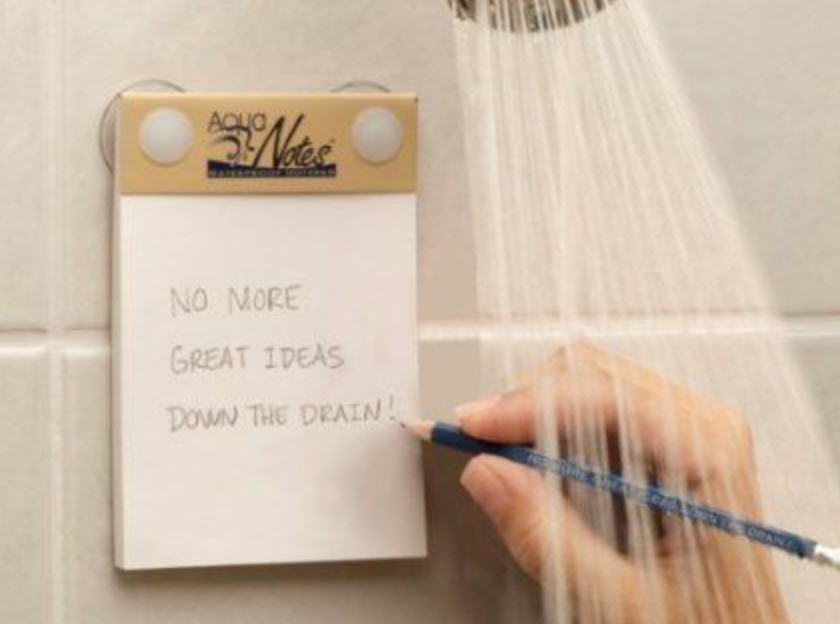

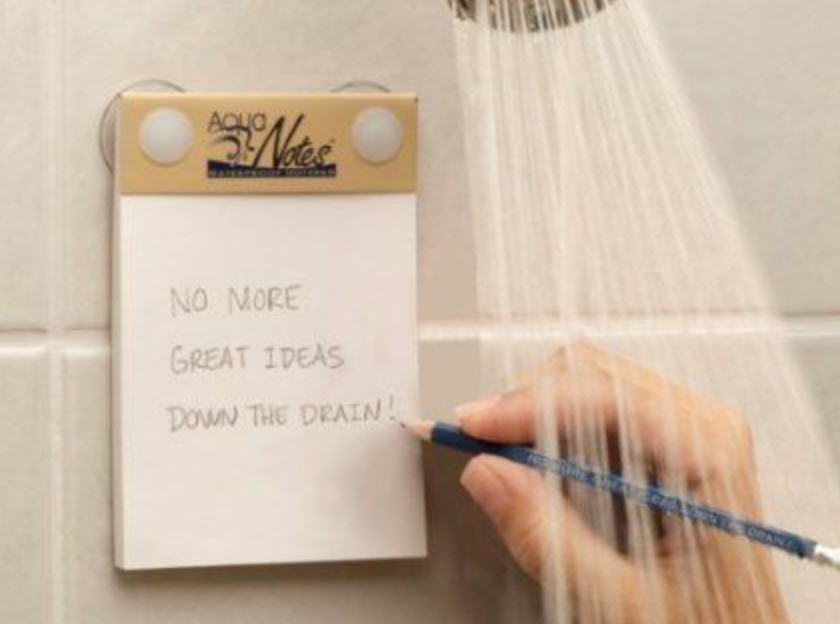

Some writers find inspiration in a shower: what then? If you’re a shower-inspiration writer, consider wet note-pad paper.

When inspiration hits in the middle of the night and you don’t want to wake your partner, use Nite Note or similar product — a pad or pen that lights up.

By equipping your world with note-taking tools you’re sending a message to your brain that you’re listening. Be ready.

Other posts in this series:

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

A writer’s routine: pantster or plotter?

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative head space

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

A writer’s routine: where to write

A writer’s routine: on resisting an outline

A writer’s routine: how to be productive

Opening image from “A Most Delicate Art” at BibliOdyssey.

by Sandra Gulland | Sep 30, 2014 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

A friend asks:

When you first started your career as a writer, was there something you were doing each day, which you now know to be unproductive?

When I look back on my early days, in fact, I’m amazed that I accomplished as much as I did. My husband was often away, and I had two children, a dog, horses, a garden and chickens to look after. Plus, I was still editing free-lance and active in my community: co-editor of a newsletter and volunteer principal of an alternative school.

How did I do it?

The magic word: no

The answer, in part, is that I was young, but mainly I learned to start saying NO—perhaps the most important word in a writer’s vocabulary.

When I got the contract to write the Trilogy the first thing I realized is that I would have to give up my community volunteer work.

I didn’t want to, but there is a limit to how much one can do. I couldn’t fool myself into thinking that my life would carry on a usual and that somehow these novels would magically get written. Something had to give.

I also put my paid editorial work on the back burner: I gave my best hours—my morning hours—to writing.

A novel needs room to grow. Ask yourself: What can I give up? How can I make more time in my day?

Make writing the priority. Put it at the top of your To Do List.

Write Time: Guide to the Creative Process, from Vision through Revision-and Beyond (formerly titled A Writer’s Time) by Kenneth Atchity is a good book on how to get a book written and—most importantly—revised. Unlike a lot of books on writing, his is practical, the nuts ‘n bolts of tackling a big job.

One of Atchity’s suggestions that I have found useful all these many years is to include holidays in the writing process: by finishing drafts before a holiday, you give it time to “age,” and return to it with a fresh perspective.

Also in the making-breaks-work-for-you vein (a blog post): The New Habit Challenge.

Other posts in this series:

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

A writer’s routine: pantster or plotter?

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative head space

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

A writer’s routine: where to write

A writer’s routine: on resisting an outline

{Illustration at top is from “A Most Delicate Art” at BibliOdyssey.}

by Sandra Gulland | Sep 28, 2014 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

A friend asks:

What have you learned over the course of your career that you wish you knew at the beginning, in terms of your writing routine/productivity?

I wish I had known how important it was to outline before beginning to write. I might have saved myself years of fruitless effort.

Resisting outlining

Like all novice writers, and many very experienced writers as well, I detested the thought of outlining in large part because I didn’t understand that an outline is an early draft (a conceptual draft) of the story, but also because I associated outlining with the dreaded word plot.

One reason I initially leaned toward writing historical fiction was that I mistakenly thought that the plot was already there, laid out before me in the historical record.

Wrong, wrong, wrong!

I also felt that since I was “no good” at creating a plot, I would be sidestepping this weakness by writing biographical historical fiction.

Wrong again.

What I’ve learned over all these many years is that:

1) history is merely the stuff from which a plot must be created;

2) a writer can — and must — learn about plotting.

What’s wrong with being a Pantster?

Some writers—often the “pantsters,” those who proclaim against outline—have an intuitive feel for story, gleaned from decades of reading and revising. They also usually take years longer to find their story arc.

A novel will take years to write one way or another, but without a plot outline, it will take—I venture to guess—twice as long.

So you decide:

a pantster novel: 8 years

a plotter novel: 4 years

But aren’t plotter novels “commercial,” and pantster novels “literary”?

Wrong again. There are both plotter and pantster novelists in every genre.

Why writers resist writing an outline …

1) It’s hard.

2) It’s abstract, conceptual.

3) (For some) One needs to—or should—first study the mechanics of plot.

Imagine that you are going to build a house. It’s kind of fun to think of ordering in piles of lumber and just begin sawing and hammering away.

You can see where this is leading.

Instead, of course, a builder begins with a plan, a plan that will go through many, many drafts. Once the plan is fully refined, the building begins. But even then, changes will be made and it’s “back to the drawing table,” as they say.

In the case of a novel, rather large changes will often be made, and then, too, it’s “back to the drawing table”—that is, back to the outline.

The many shapes and sizes of an outline

There is a mistaken idea that an outline puts a writer in a straightjacket and that the actual writing then becomes formulaic, mechanical and … Well, one often sees the word boring used.

This is not how it works.

A novel is conceived in imagination. And then notes. And then more notes: voices, scenes, snippets of dialogue. These begin to congeal, cluster, take form. At some “quickening” point, these notes can be laid out (or, if on computer, shifted around) to form a story arc.

And there you have it: an outline. It may be a one-page sketch, a stack of index cards, or a 40-page document. (My preference at this time is to create a scene-by-scene outline.) There will be gaps, places you know something has to happen, but you don’t yet know what it is or how it’s going to come about. What you do have is a shape: a beginning, a middle and an end.

For the next draft, the first in fully written form, and for all the many drafts that will come after, many things will change. But without an initial “conceptual” draft, you will be looking for the story instead of fulfilling the story: and that’s the difference.

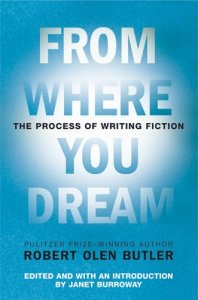

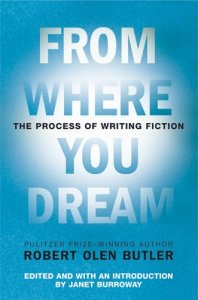

Required reading! From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction, by Robert Olen Butler—specifically Chapter Five, “A Writer Prepares.”

When it comes to plot, I’m a big fan of books by screenwriters, the plot-masters. Here are my favourites:

Save the Cat, by Blake Snyder. I especially recommend this book because it is short, amusing, and to the point.

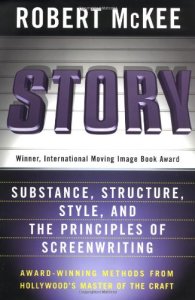

Story, by Robert McKee.

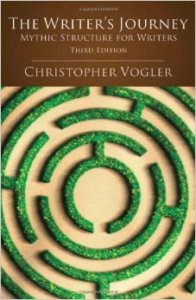

The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers, by Christopher Vogler. I love this book. It’s especially relevant with respect to character, and the role of different characters in a story.

For these and other books on screenwriting: “Top 10 Screenwriting Books.”

Other posts in this series:

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

A writer’s routine: pantster or plotter?

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative head space

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

A writer’s routine: where to write

{Illustration at top is from “A Most Delicate Art” at BibliOdyssey.}