by Sandra Gulland | Nov 22, 2018 | Adventures of a Writing Life, My Life, Recommended Books, Movies, Podcasts, etc., The Josephine B. Trilogy |

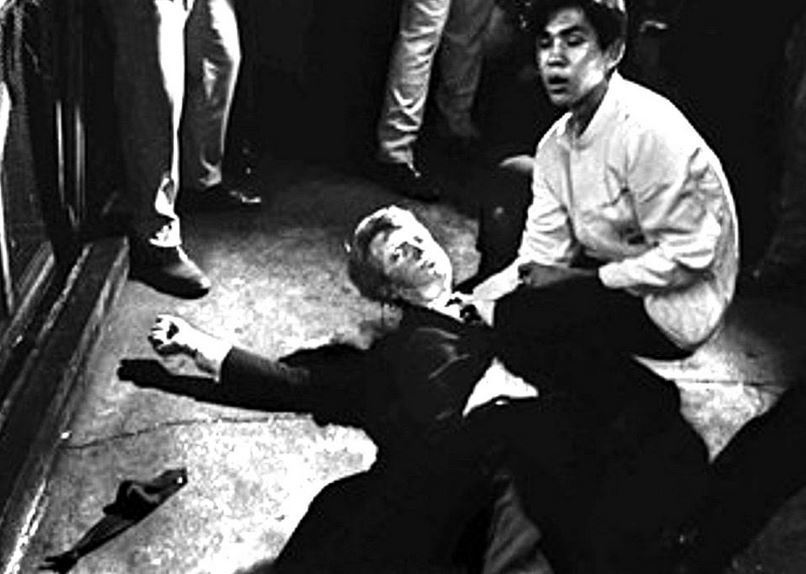

JFK was murdered on November 22, 1963, fifty-five years ago today. I was nineteen and in university. I don’t remember the moment I learned — How is that possible? — but the images and the shock of it are indelible in my memory.

I have since read a moving biographical historical novel, titled, simply, Nov 22, 1963, by Adam Braver.

The assassination was made all the more horrifying in learning in this novel that JFK and Jackie had recently suffered the death of a baby. This tragic trip to Texas with her husband was Jackie’s brave first public event.

A Berkeley childhood

I grew up in Berkeley, California. Air raid siren drills were common; there was always the fear of annihilation. At Girl Scout camp, I remember a cloudy day being attributed to the test of a nuclear bomb in near-by Nevada. I was assigned to write stories about our last day alive in Grade School.

My high school years in Berkeley were vivid with protest. I was a proud member of Students for a Democratic Society. In English, I sat next to Tracy Simms, who led the very first sit-in against a hotel in San Francisco that did not hire Blacks.

These were intense years, rich with both excitement and fear. The Whole Earth Catalogue was Google in print. It’s message was: “You can do anything, go anywhere. Here are the tools.” It was a powerful concept, and an entire generation took it to heart.

Although I don’t remember the moment I learned of Kennedy’s assassination, I remember, vividly, the night of the Bay of Pigs on April 17, 1961, two-a-half years before. I was seventeen, living in San Francisco with roommates in the Castro district, going to San Francisco State. We believed that it could be the end of the world, our last night alive. (In fact, recent scholarship shows how very close it came to being just that, by an accident of communication.) I imagine that there was a surge in births nine months later, for many young couples succumbed. Why wait?

The three assassinations

On April 4, 1968, four-and-a-half years after Kennedy was killed, Martin Luther King was assassinated. I was twenty-one, married and working in a factory in Belmont, California — a factory that provided micro-chips for fighter jets. I had to sign a Loyalty Oath to work there. I remember the Ohio Flute Society (or something similar) being listed as one of the suspicious organizations.

I couldn’t sleep the night of April 4. I got up and went downstairs. It was very late. I turned on the TV: screams, a newscaster’s urgent voice, flickering images. King had been shot.

The next morning, at the factory, a white guy riding a trolley yelled, fist raised, “We got another one!”

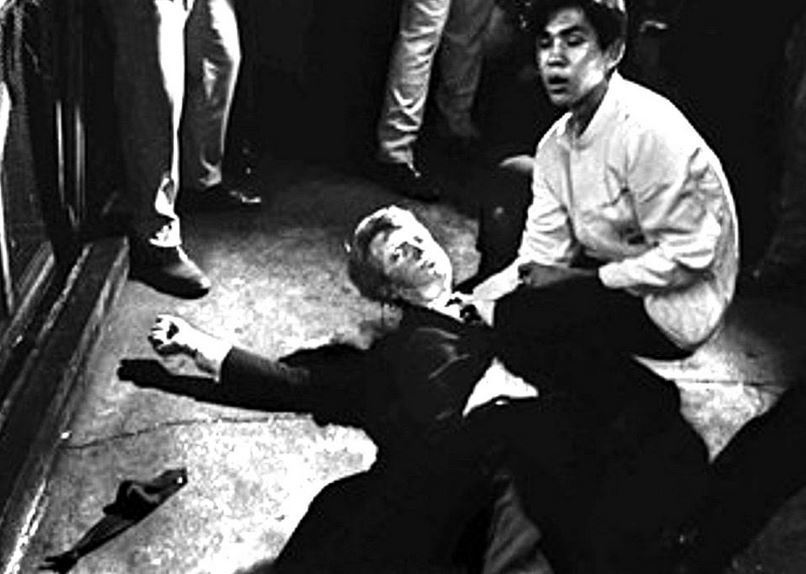

And then, only two months later, on June 6, the same thing. I couldn’t sleep, I went downstairs and turned on the TV. A newscaster’s urgent voice, flickering images, screams. Bobby Kennedy had been shot.

I’d been canvassing for him, handing out leaflets — it was my first involvement in a political campaign. Belmont was a conservative town, yet the day after Bobby Kennedy’s death there was, I was told, a rash of suicides.

A decision

That morning, the morning after, my then husband and I went to Half Moon Bay. Sitting on a sand dune overlooking the Pacific, stunned by the news, I said I wanted to move. Away. To another country. Bobby Kennedy’s death was the straw that broke my back.

And thus the decision was made to leave my country of birth for a more peaceful realm. Move to Canada — a “healing” country in the words of the wonderful Carol Shields, who had herself immigrated to Canada from the US. I found it to be just that.

A Canadian citizen now, I have never regretted that move. Even so, a part of me will always be American. A part of me will always love that country — love it, and fear for it. Which is one reason I, like so many others, am addicted to the horrifying daily news.

Are things worse now than they were during those violent and tumultuous years? I would say yes, although in a more institutional way. I believe in democracy, and greatly fear for it.

by Sandra Gulland | Nov 20, 2018 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Biographical Fiction, On Character Development, Recommended Books, Movies, Podcasts, etc., The Writing Process |

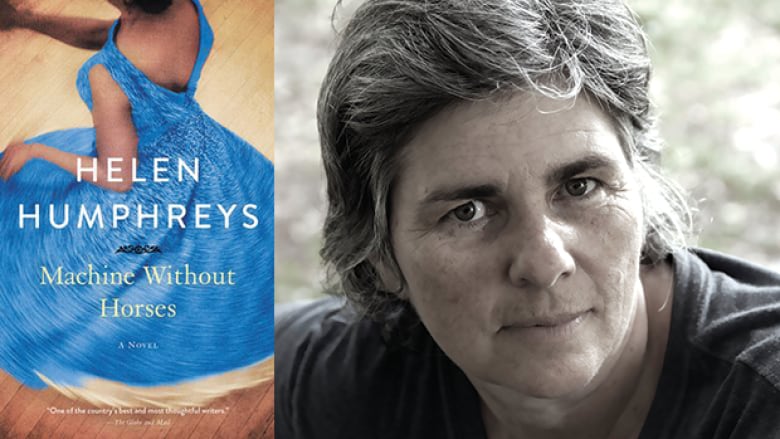

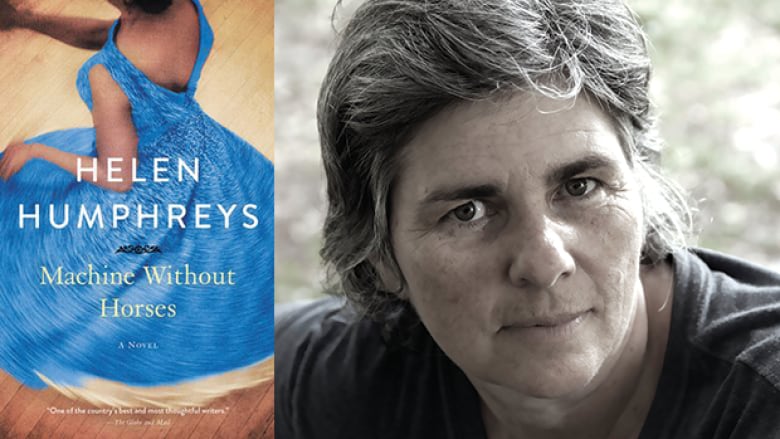

The two reviews I read of Helen Humphreys newest publication, Machine Without Horses, were somewhat negative, claiming that the combination of memoir and fiction simply do not work. Humphreys is one of my favorite writers. She never fails to please, and so I was curious.

I’ve just now finished it and I beg to differ. I found this to be an innovative and inspiring work.

Machine Without Horses is billed as a novel: therein, I think, lies the problem. The first half of this “novel” is a memoir of the author researching and thinking through how to write about her subject, Megan Boyd, a famous fishing fly maker from Scotland.

I particularly love the author’s thoughts on writing. Coming from Humphreys, these are gold. Here are some examples of her thoughts on character development:

The beginning of a life is often the start of the story. Character is formed from the early incidents and accidents, from sudden trauma, or reassuring constancy. These are more important than aspects of personality because they are the ground on which the inherent nature of the person blossoms or is stifled. (Page 7)

I particularly like this because it jives with my current thoughts on character development. (See my thoughts regarding the book Story Genius.)

When I set about making a story, one of the first things I think about is the motivation of the main character. What is it that they want? What are they driven by? Story is created from combining a character’s motivation with their circumstances. (Page 16)

In this section of Machine Without Horses, the author is taking lessons on making fishing flies.

“Anything will help,” I confess.”I’m trying to work my way inside her mind before I write about her.”(page 24)

Her teacher Paul asks, “How do you get inside someone’s head to write about them? Especially someone who was a real person?”

This is the sixty-million-dollar question, and one that I don’t really have a definitive answer for because I’m constantly shifting my thinking about how to accomplish this kind of transference. It is hard enough to be oneself. How can we effectively become someone else? (pages 26/27)

This quote pertains especially to writing biographical fiction:

The trouble with writing a novel is that there are so many ways to make mistakes that you just have to give up on the idea of getting it right. Instead, you have to choose a few aspects to remain faithful to and do your best to make everything else as believable as possible for the reader. (page 33)

I especially love this passage:

A writer must slowly build a story and characters, as though they were making a machine, with each part intersecting snugly, each sentence casting forward to hook onto the next. You must lean the way they lean, have the understanding they have, never step outside the limits you have determined for them. You cannot just kill them off with no real warning. It will feel unbelievable to readers and they will stop trusting your story. Fiction is measured and reassuring in a way that life isn’t, and perhaps that’s why we read it, and also why I write. (pages 89/90)

Throughout this section, there are now and again descriptions that echo fly fishing, i.e. “each sentence casting forward to hook onto the next.”

Starting a novel is like starting a love affair. It demands full and tireless attention or feelings could change. Commitment takes time, and so there must be a rush of passion at the beginning. This means that the other life of the writer, the “real life,” has to fade into the background ground for a while. (Page 11–12)

Not exactly like being in love, however:

When I’m working on a book, I just wear the same clothes day after day, eat the same food with no variation. Novel–writing and depression have a great deal in common, as it turns out. (page 41)

This is a spare book, only 267 pages, and this section on Humphreys preparing to write about her subject accounts for more than half of it. The last 120 pages is the work itself, a beautifully spare biographical novella about Helen Boyd.

Exquisite.