by Sandra Gulland | Nov 21, 2014 | Baroque Explorations |

It’s simply astonishing what one can now find on-line. In the way of any wander through library stacks, I came upon this title on Gallica.bnf.fr, the French national library on-line:

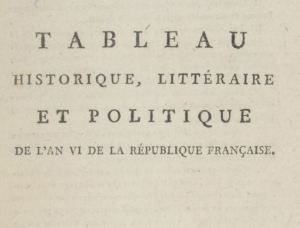

Tableau historique, littéraire et politique de l’an VI de la Républic française.

Of course it was not at all what I was looking for, but although “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometime, you find you get what you need.” :-)

I love the way the digital book opens with its cover:

And then turns to the marbled end-paper:

Here’s a crop of the title page:

(You can almost feel the rich texture of the paper.)

And then, the first chapter division:

What caught my attention “leafing” through this book was the section on legislation, a daily account of laws passed in the years 1798-1799.

They are very detailed: they needed to be. The French government was (once again) creating a government from scratch. Laws mentioned cover passport regulations, import duties, the re-establishment of a national lottery, the legislateurs’ own schedule (they will no longer meet on décadis (the end of the 10-day week), patents, manufacture of goods, the “uniform” to be worn by the members of the legislature …

“…habit français, couleur bleu national, croisé et dépassant le genou. Ceinture de soie tricolore, avec des franges d’or. Manteau écarlate à la grecque, orné de broderie en laine. Bonnet de velours, portant une aigrette tricolore.” – page 142

Alas, I am unable to find an illustration of this costume. No doubt they were somewhat more circumspect than those from 1796. Below left, Executive Director from 1796, compared to Napoleon’s uniform of choice as First Consul on the right:

The legal record is many pages long, but I’ll note a few:

One law passed condemns to death those who rob by force or violence. This is significant because violent crime had become rampant.

Marriages (which must be civil) could only be held on décadis.

One significant law, passed 12 Nivose, an VIII (January 1, 1799), declares that Blacks born in Africa or in foreign colonies, and transferred to French islands, were free as soon as they step foot on French soil. The Revolutionary government had several years before outlawed slavery in France, but I don’t believe that it had gone so far as to declare it illegal in its colonies. (I should note that Napoleon will eventually reinstate slavery in the French colonies, and no: it was not Josephine’s doing.)

It’s delightful how worthwhile procrastinating can be. I found an excellent Revolutionary calendar (more on that later), learned the date when there was an eclipse of the moon, what the new national fêtes were to be, and much, much more.

by Sandra Gulland | Oct 24, 2014 | Baroque Explorations |

Fear of Ebola is helping me understand how people felt and responded to fear of the plague—the Black Death—in the Napoleonic era.

During Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, there was an outbreak of the bubonic plague after the French capture of Jaffa on 7 March 1799. The news that there was plague in Egypt must have terrified the families and friends of the soldiers who were fighting there.

This from Wikipedia:

Before leaving Jaffa, Bonaparte set up a divan for the city along with a large hospital on the site of the Carmelite monastery at Mount Carmel to treat those of his soldiers who had caught the plague, whose symptoms had been seen among them since the start of the siege. A report from generals Bon and Rampon on the plague’s spread worried Bonaparte. To calm his army, it is said he went into the sufferers’ rooms, spoke with and consoled the sick and touched them, saying “See, it’s nothing,” then left the hospital and told those who thought his actions unwise “It was my duty, I’m commander-in-chief.”

However, some later historians state that Napoleon avoided touching or even meeting plague-sufferers to avoid catching it and that his visits to the sick were invented by later Napoleonic propaganda.

For example, long after the campaign, Antoine-Jean Gros produced the propaganda painting Bonaparte visiting the plague-victims of Jaffa in 1804. This showed Napoleon touching a sick man’s body, modelling him on an Ancien Régime king-healer touching sufferers from the “King’s Evil” during his coronation rites – this was no coincidence, since 1804 was the year Napoleon Bonaparte crowned himself emperor.

Quarantine used to contain the spread of contagious diseases

One way of containing the spread of a highly-contageous disease in Europe was quarantine:

The practice of quarantine, as we know it, began during the 14th century in an effort to protect coastal cities from plague epidemics. Ships arriving in Venice from infected ports were required to sit at anchor for 40 days before landing. This practice, called quarantine, was derived from the Italian words quaranta giorni, which mean 40 days.

When Napoleon returned to France from Egypt, landing in Fréjus, he was criticized for not having observed the obligatory quarantine imposed on people coming from a plague-infected country. The breech of the quarantine laws was no small matter: it was punishable even with death.

According to Napoleon’s secretary Bourrienne, however, when the citizens of the village swarmed Napoleon’s boat in their enthusiasm,

In vain we endeavoured to keep the people off; we were fairly lifted up, and carried on shore. When we told the crowd of men and women the danger they ran [of contracting the Plague] they all cried out, “We’d rather have the plague than the Austrians.”

And later:

When we consider that 500 people landed and all the goods brought from Alexandria, where the plague had been raging during the summer…[it was fortunate] that France and Europe were spared.

Related links

On Ebola quarantine today and in years past: Ebola is ‘Jerking Us Back to the 19th Century

Entire City Quarantined in China After Man Dies of the Bubonic Plague

Feeling Swinish: Or the Origins of “Pandemic”

Painting at top: Napoleon visiting the plague victims of Jaffa, by Antoine-Jean Gros.

by Sandra Gulland | Oct 18, 2014 | Baroque Explorations |

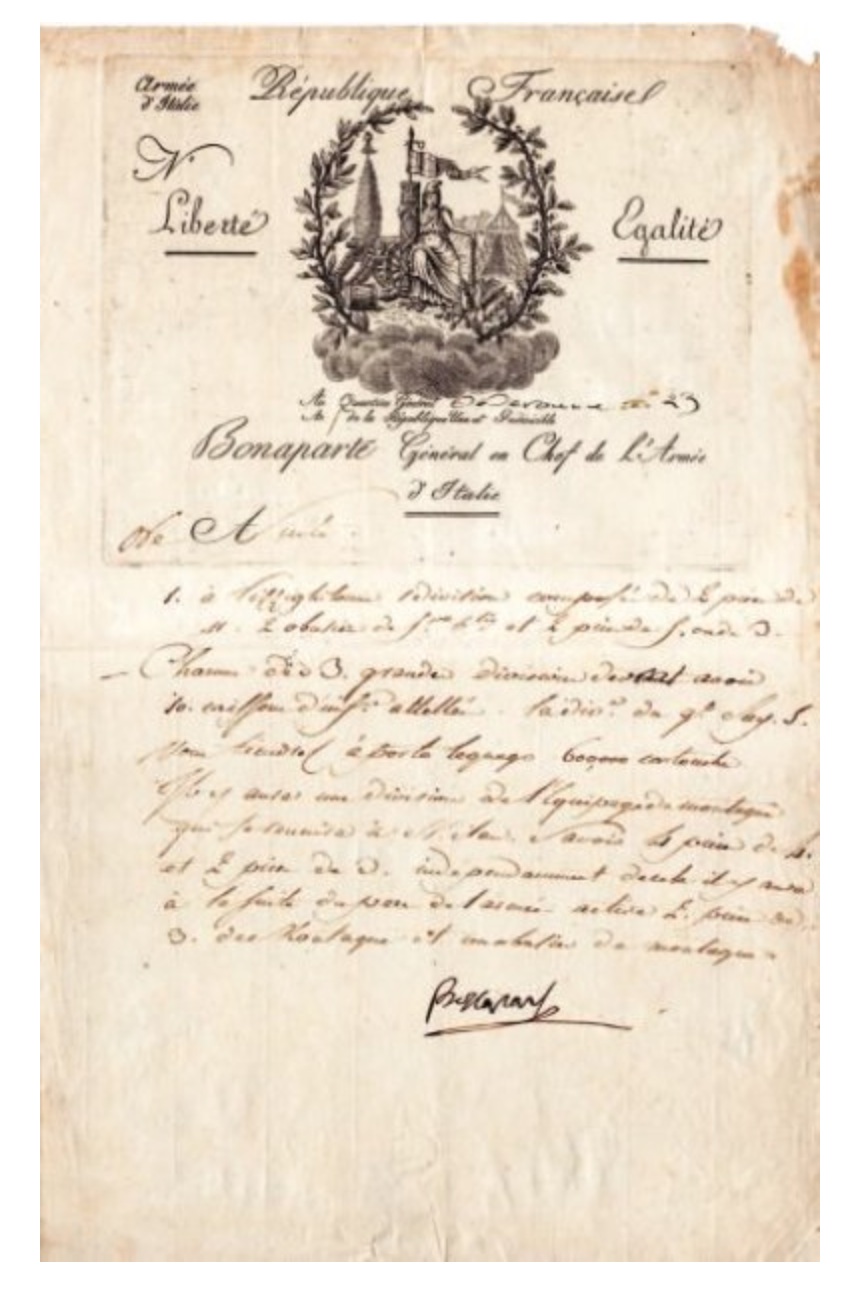

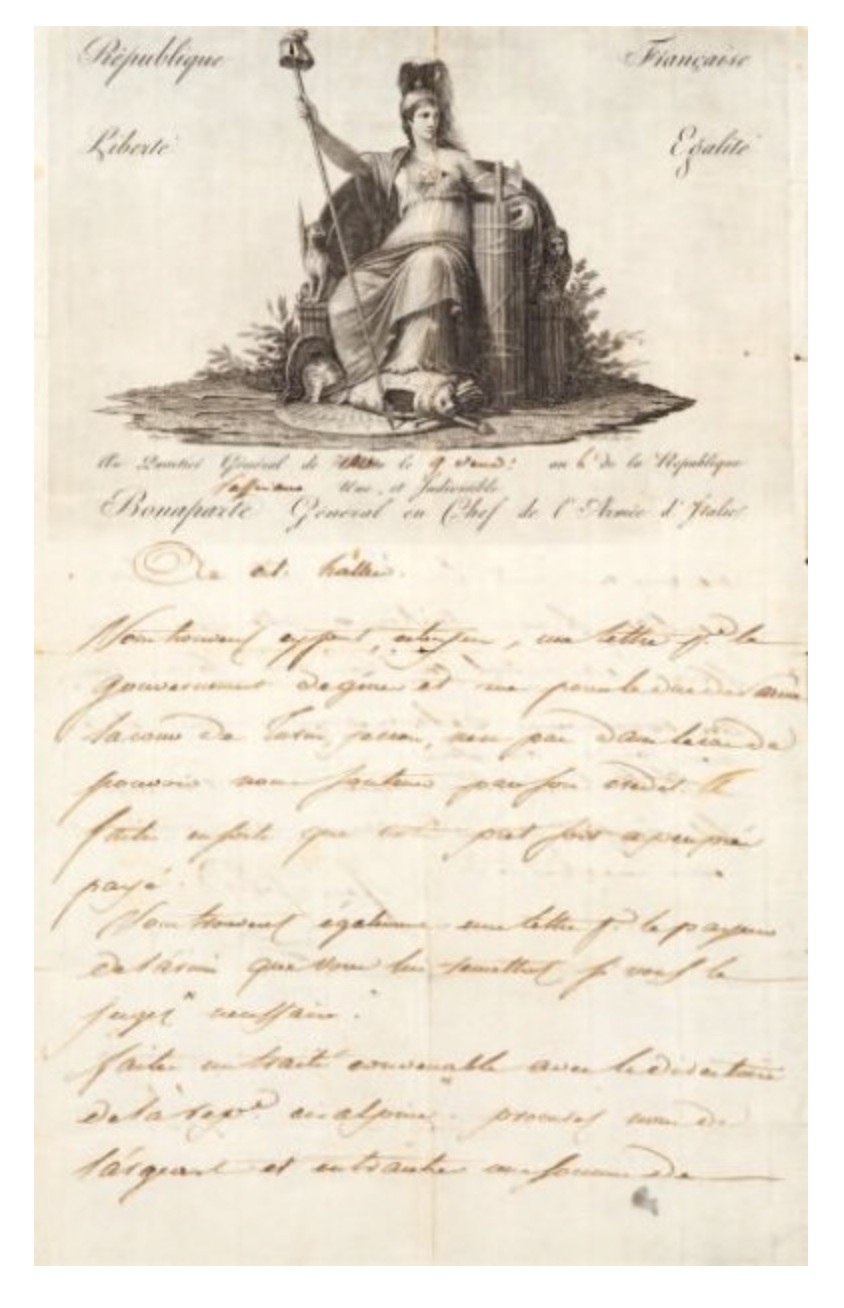

I have been falling victim to research excitement. On one search, I came upon these letters, which did not answer my questions, but were too exciting to pass by.

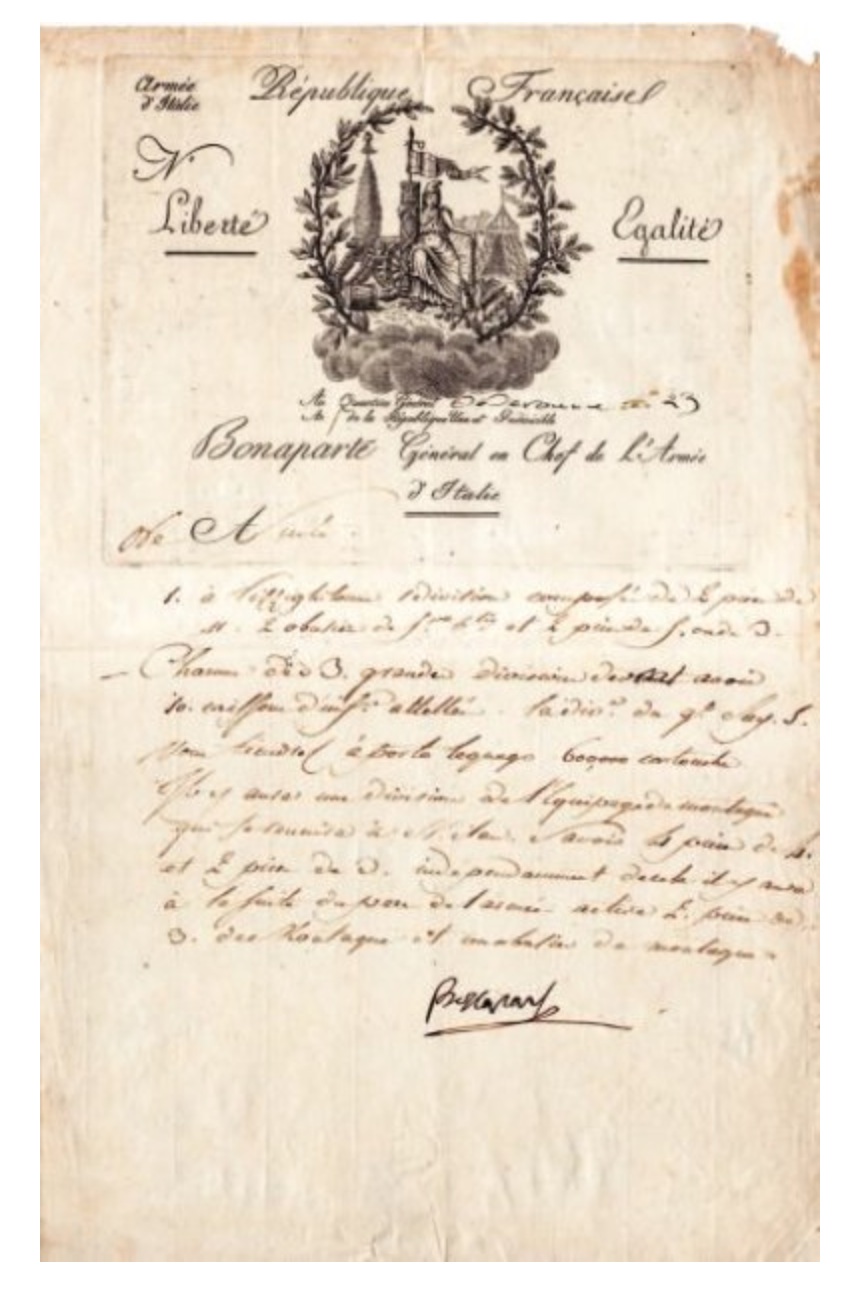

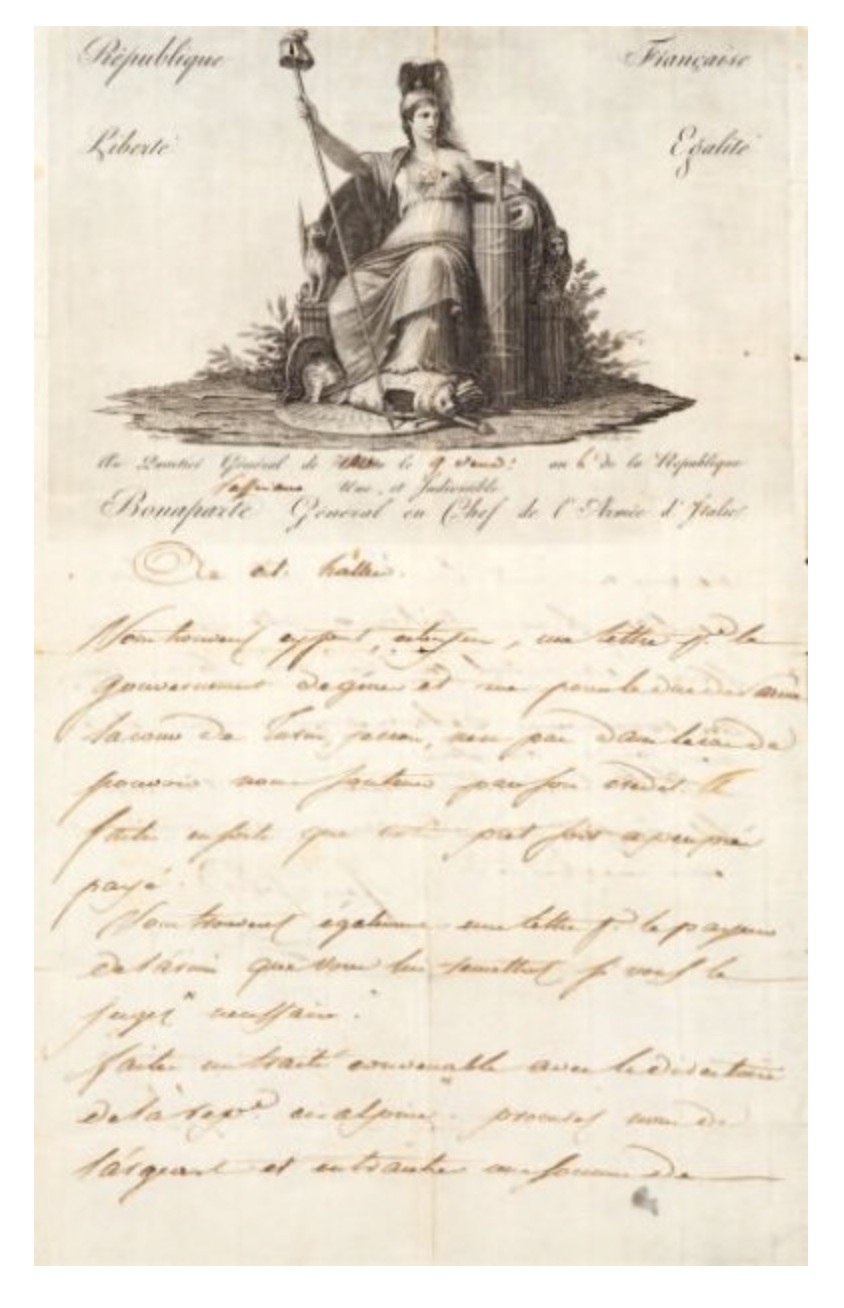

All of the letters are part of an auction of letters and manuscripts. The first two were dictated by Napoleon to Géraud Christophe Duroc, displaying Duroc’s lovely handwriting. Since he is a significant character in the Young Adult novels I am writing, seeing his graceful, elegant handwriting speaks volumes.

This first one was written on November 13, 1796, in Verona. (See here for details.)

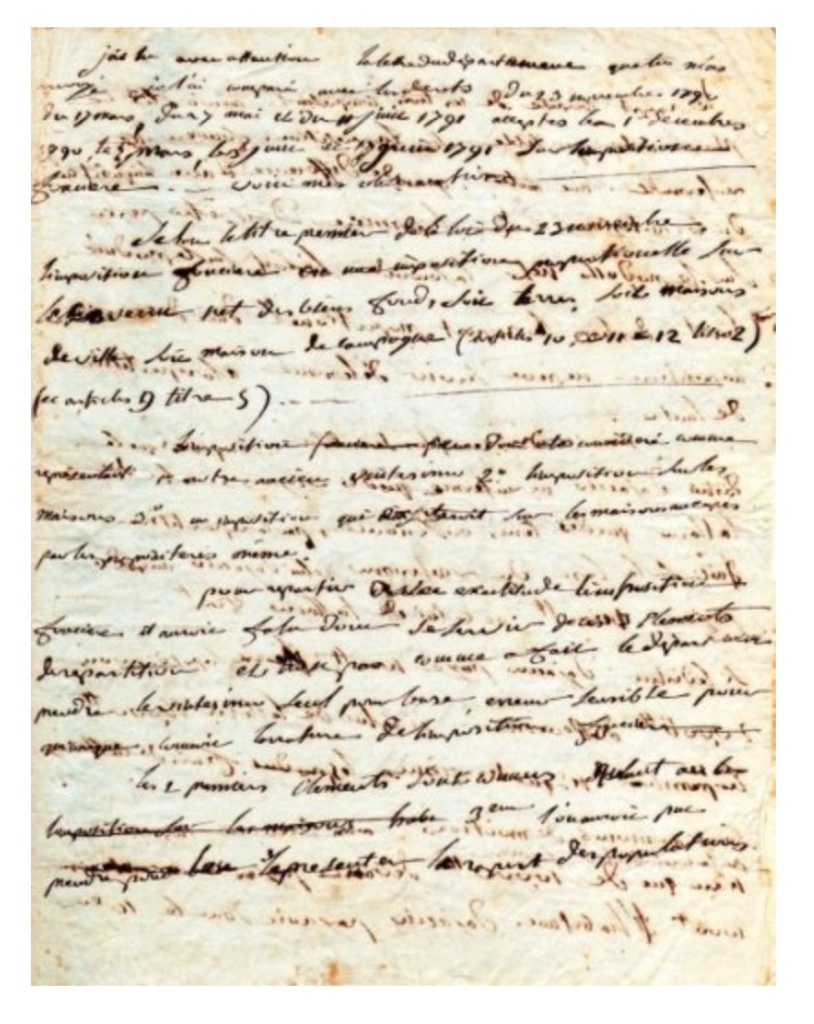

This second letter, also dictated by Napoleon and written by Duroc, was sent on September 30, 1797, from Passeriano, Italy, during the peace negotiations with Austria.

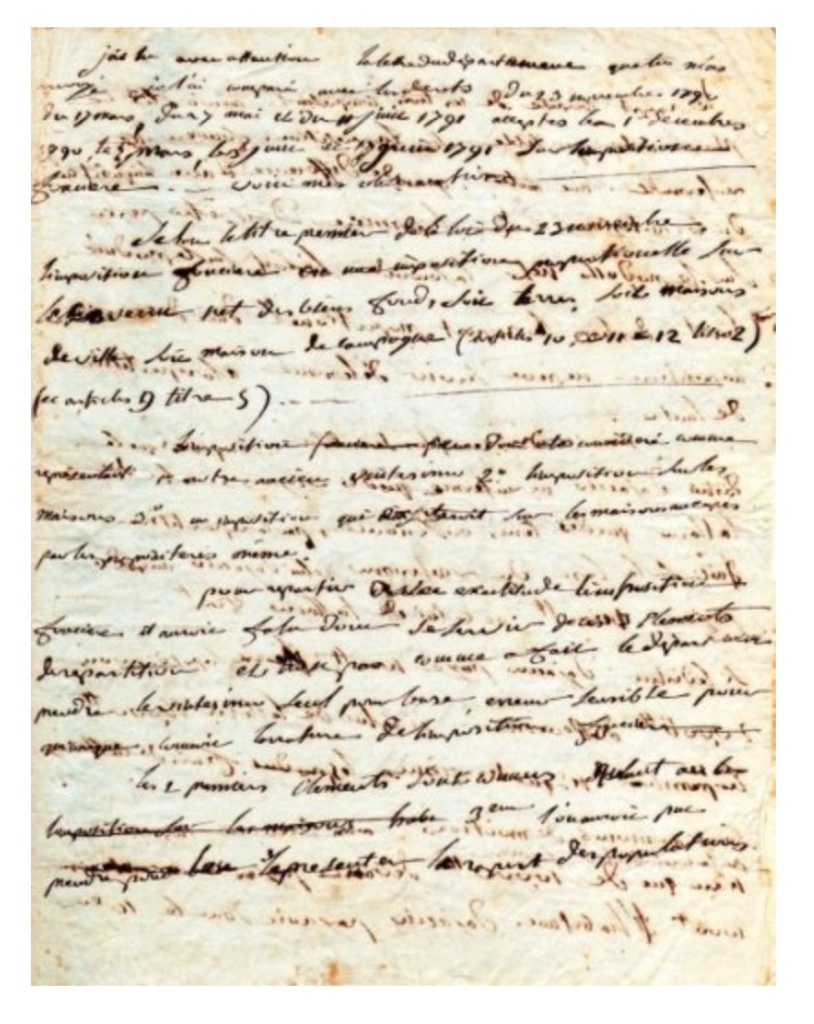

This next letter was written by Napoleon to his brother Joseph in October of 1792 from Ajaccio, Corsica, and it helps understand why Napoleon had need of a secretary. Napoleon’s handwriting was famously difficult to read.

This last one was written by Josephine on May 14, 1809, to her son Eugène.

It simply thrills me to see her signature.

by Sandra Gulland | Oct 18, 2014 | Baroque Explorations |

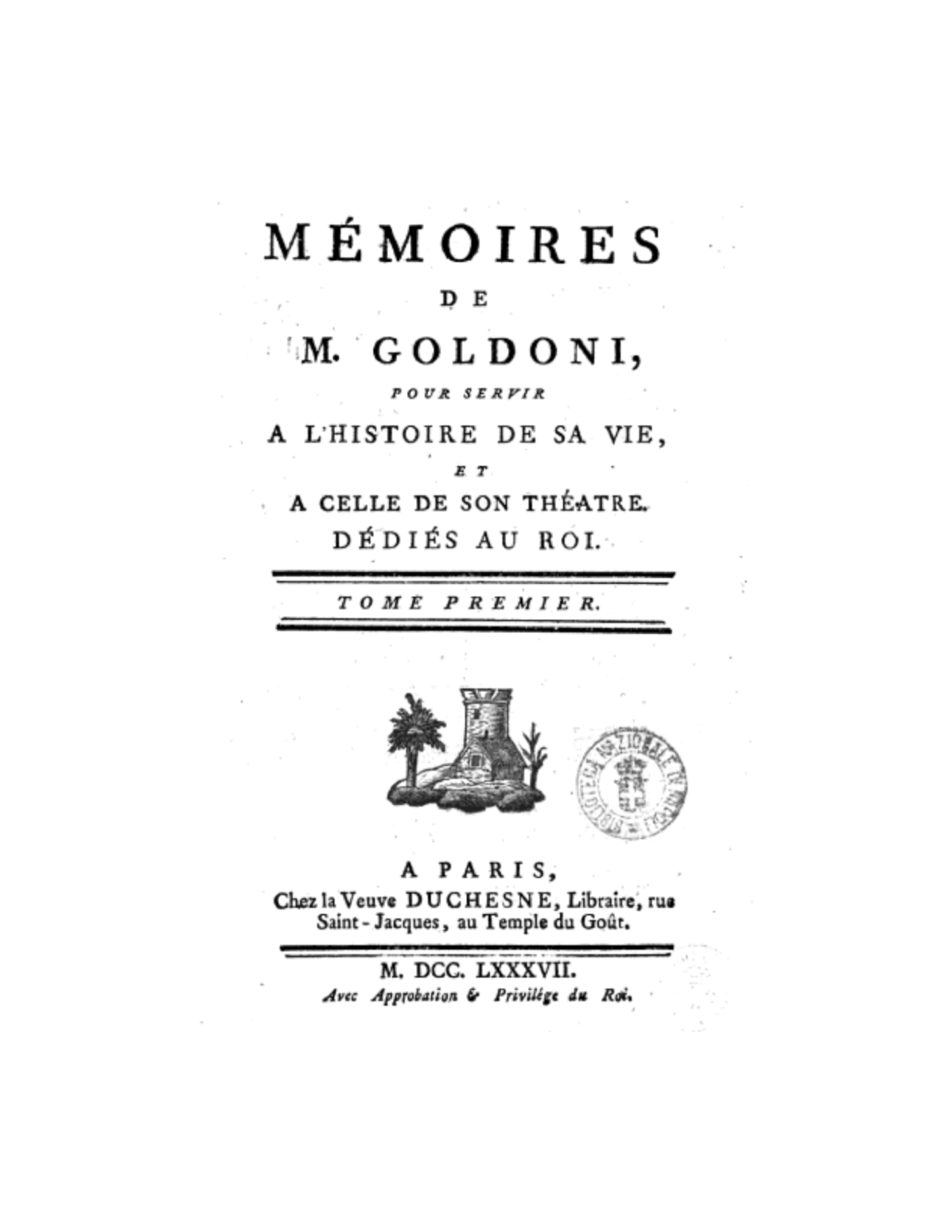

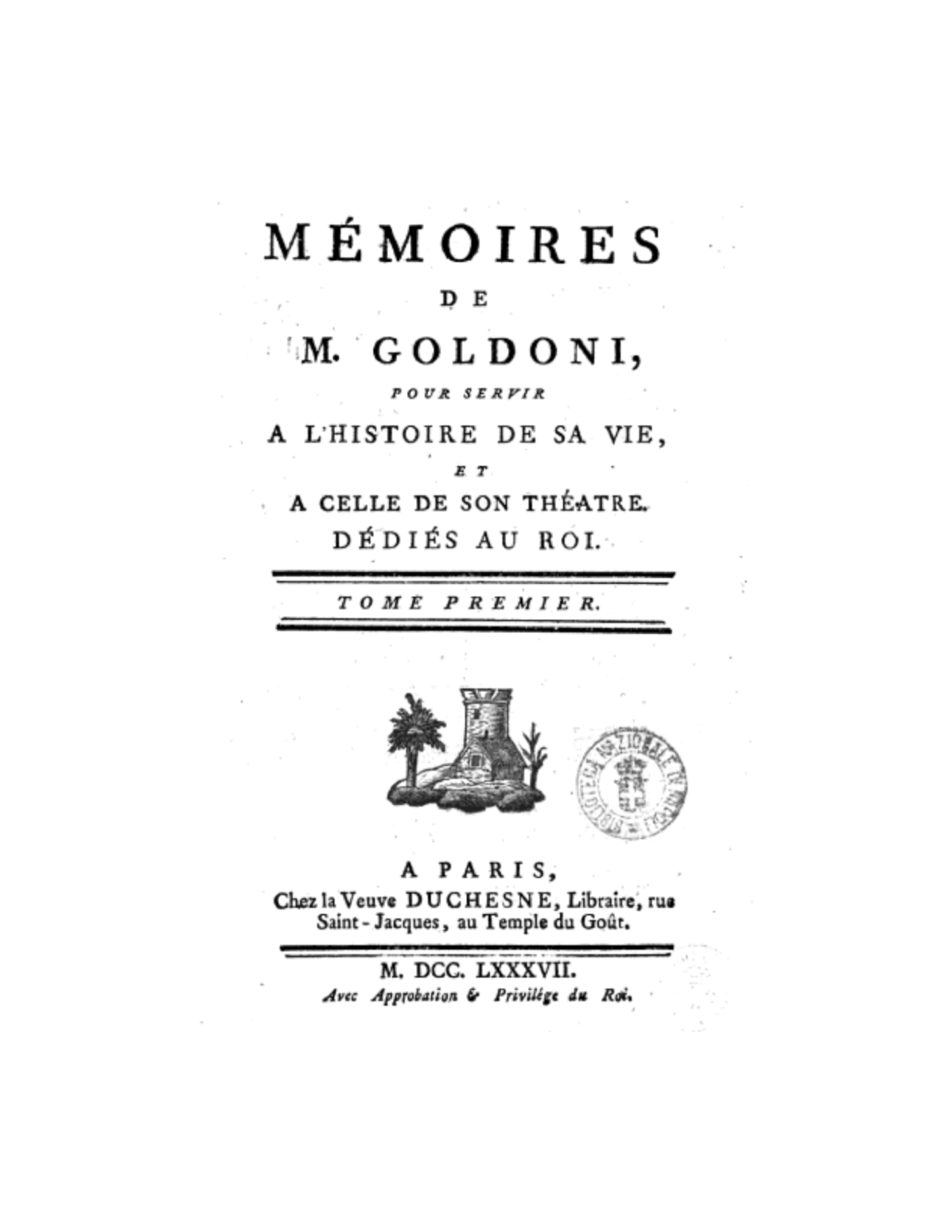

It continues to amaze me what one can find on-line now. I was searching for pre-1805 publications that contained the name Madame Campan, the founder and director of the highly esteemed boarding school Josephine’s daughter, Hortense de Beauharnais, went to.*

I was charmed to find Madame Campan’s name listed in this title:

At the beginning of the Mémoires is thank you note to the subscribers, a very long list which includes many members of the Court (including the King and Queen). I gather that all these people paid in advance in order for the Mémoires to be published. This reminded me immediately of our on-line crowdsourcing like Kickstarter.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

*I was on-line trying to find out the name of the school as it had been referred to at the time. Here are two possibilities:

L’Institut National des Jeunes Filles/National Institution for Young Women

I’ve also seen (but only in English): National Institution for the Education of Young Women.

l’Institut national de Saint-Germain/The National Institution of Saint-Germain

I have doubts about this name because during the Revolution the name of Saint-Germain-en-Laye had been changed to Montagne-Bon-Air. It was changed back 28 février 1795, but would Madame Campan have been so bold as to jump immediately on the reversal?