Memories of a violent era — and why I became a Canadian

JFK was murdered on November 22, 1963, fifty-five years ago today. I was nineteen and in university. I don’t remember the moment I learned — How is that possible? — but the images and the shock of it are indelible in my memory.

I have since read a moving biographical historical novel, titled, simply, Nov 22, 1963, by Adam Braver.

The assassination was made all the more horrifying in learning in this novel that JFK and Jackie had recently suffered the death of a baby. This tragic trip to Texas with her husband was Jackie’s brave first public event.

A Berkeley childhood

I grew up in Berkeley, California. Air raid siren drills were common; there was always the fear of annihilation. At Girl Scout camp, I remember a cloudy day being attributed to the test of a nuclear bomb in near-by Nevada. I was assigned to write stories about our last day alive in Grade School.

My high school years in Berkeley were vivid with protest. I was a proud member of Students for a Democratic Society. In English, I sat next to Tracy Simms, who led the very first sit-in against a hotel in San Francisco that did not hire Blacks.

These were intense years, rich with both excitement and fear. The Whole Earth Catalogue was Google in print. It’s message was: “You can do anything, go anywhere. Here are the tools.” It was a powerful concept, and an entire generation took it to heart.

Although I don’t remember the moment I learned of Kennedy’s assassination, I remember, vividly, the night of the Bay of Pigs on April 17, 1961, two-a-half years before. I was seventeen, living in San Francisco with roommates in the Castro district, going to San Francisco State. We believed that it could be the end of the world, our last night alive. (In fact, recent scholarship shows how very close it came to being just that, by an accident of communication.) I imagine that there was a surge in births nine months later, for many young couples succumbed. Why wait?

The three assassinations

On April 4, 1968, four-and-a-half years after Kennedy was killed, Martin Luther King was assassinated. I was twenty-one, married and working in a factory in Belmont, California — a factory that provided micro-chips for fighter jets. I had to sign a Loyalty Oath to work there. I remember the Ohio Flute Society (or something similar) being listed as one of the suspicious organizations.

I couldn’t sleep the night of April 4. I got up and went downstairs. It was very late. I turned on the TV: screams, a newscaster’s urgent voice, flickering images. King had been shot.

The next morning, at the factory, a white guy riding a trolley yelled, fist raised, “We got another one!”

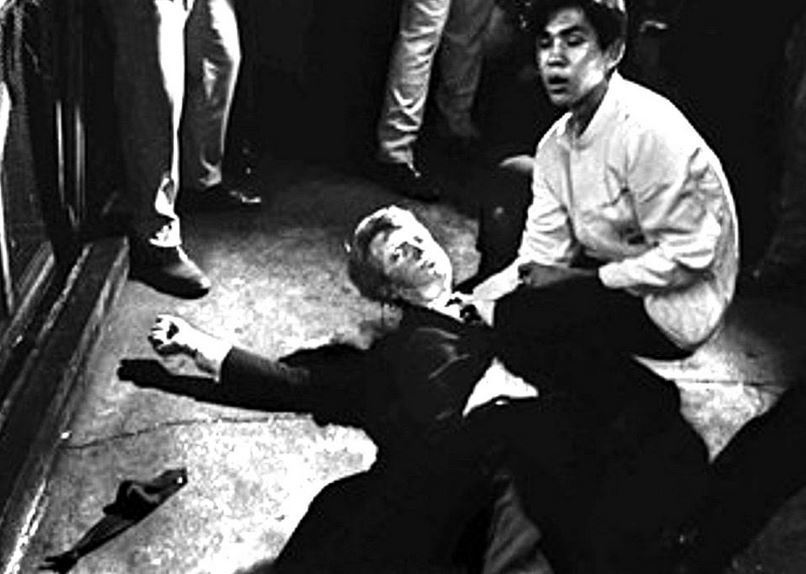

And then, only two months later, on June 6, the same thing. I couldn’t sleep, I went downstairs and turned on the TV. A newscaster’s urgent voice, flickering images, screams. Bobby Kennedy had been shot.

I’d been canvassing for him, handing out leaflets — it was my first involvement in a political campaign. Belmont was a conservative town, yet the day after Bobby Kennedy’s death there was, I was told, a rash of suicides.

A decision

That morning, the morning after, my then husband and I went to Half Moon Bay. Sitting on a sand dune overlooking the Pacific, stunned by the news, I said I wanted to move. Away. To another country. Bobby Kennedy’s death was the straw that broke my back.

And thus the decision was made to leave my country of birth for a more peaceful realm. Move to Canada — a “healing” country in the words of the wonderful Carol Shields, who had herself immigrated to Canada from the US. I found it to be just that.

A Canadian citizen now, I have never regretted that move. Even so, a part of me will always be American. A part of me will always love that country — love it, and fear for it. Which is one reason I, like so many others, am addicted to the horrifying daily news.

Are things worse now than they were during those violent and tumultuous years? I would say yes, although in a more institutional way. I believe in democracy, and greatly fear for it.