I’ve been addicted to the theory of the Hero’s Journey as story structure since I read Cambell’s groundbreaking work,The Hero With a Thousand Faces, in high school. It’s at the core of virtually every book I admire on plot: The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler, Save the Cat by Blake Snyder, Story by Robert McKee, The Anatomy of Story by John Truby, to name a few.

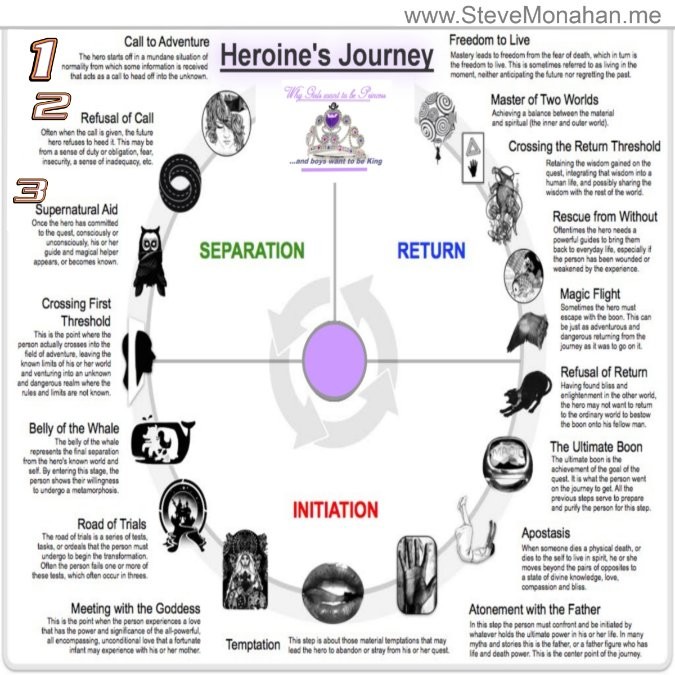

Yet, increasingly, I’ve been bothered by the feeling that there’s something missing, something that doesn’t quite fit the structure of a Heroine’s journey.

The Heroine’s Journey

There have been many alternative structures proposed (see here, and here, for example), but they didn’t really grab me.

The proposed structures felt a little forced to me. The strength of Cambell’s work is that it arose out an examination of popular stories. He began with what worked, and then looked for why. I didn’t feel that those proposing a structure for a Heroine’s Journey were evolving theories by examining actual stories.

Birth vs. Battle, a recent blog essay on Writer Unboxed by David Corbett, offers a solution. He begins by positing: “Conflict is not the engine of story.”

Right away, he has my attention. How many times have I wondered why every Hero’s Journey seems to involve a battle (what Corbett points out Ursula Le Guin called the “gladiatorial view of fiction”).

Corbett goes on to demonstrate that it isn’t conflict that creates movement, but desire.

“Conflict is desire meeting resistance.”

The three basic plot lines

Corbett states that there are “typically three plot lines in any meaningful story.” To summarize:

- The desire line… (outer pursuit)

- The yearning line… (inner pursuit)

- The connection line… (the relationships that help or hinder)

He points out that, “The most compelling stories unify these plot lines.”

(I’ve abbreviated greatly. Be sure to read his post in full.)

So far we’re on fairly familiar terrain, but Corbett differs in that he emphasizes the importance of the connection line.

The importance of connection

The traditional Hero, typically, is something of a loner. He acquires helpers and overcomes enemies, but emerges the sole victor. This model doesn’t really work for the Heroine, somehow. At least not for my heroines, much less for the heroines of the novels that truly move me.

Gin up as much conflict as you want, without desire to generate movement, yearning to create meaning, and other people to provide emotional richness and texture, all you have is sound and fury, and we all know how that phrase ends.

I was a Young Adult book editor in my 30s, editing a series of novels aimed at teen reluctant readers. It wasn’t PC — even more so at that time — but I came to the private conclusion that, in general, boys were drawn to stories that made their muscles twitch (conflict), while girls, frankly, liked to cry (connection).

This is a gross generalization, of course, and there are plenty of exceptions, but I do think it speaks to my own basic issue with the traditional conflict-based story structure.

We may be born alone and die alone but we grow through our engagement with the world—specifically, other people.

This is so refreshing. I’ve ordered THE ART OF CHARACTER; Creating Memorable Characters, for Fiction, Film and TV, Corbett’s book on writing. I look forward to learning more from him.