by Sandra Gulland | Mar 27, 2018 | Baroque Explorations, The Game of Hope, The Josephine B. Trilogy |

A master of the sound bite, Napoleon would have been in his element in this Age of Twitter. Here is a sampling of some pithy Napoleon quotes, some of which his stepdaughter Hortense views ironically in The Game of Hope.

“What a novel my life has been!”

“Great ambition is the passion of a great character. Those endowed with it may perform very good or very bad acts. All depends on the principles which direct them.”

“If you wish to be a success in the world, promise everything, deliver nothing.”

“All celebrated people lose dignity on a close view.”

“Courage is like love; it must have hope for nourishment.”

“Victory belongs to the most persevering.”

“History is the lies we all agree upon.”

“What then is, generally speaking, the truth of history? A fable agreed upon.”

“A throne is only a bench covered in velvet.”

“Our hour is marked, and no one can claim a moment of life beyond what fate has predestined.”

“A leader is a dealer in hope.”

“Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.”

What are some of your favorites? SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 6, 2018 | Baroque Explorations |

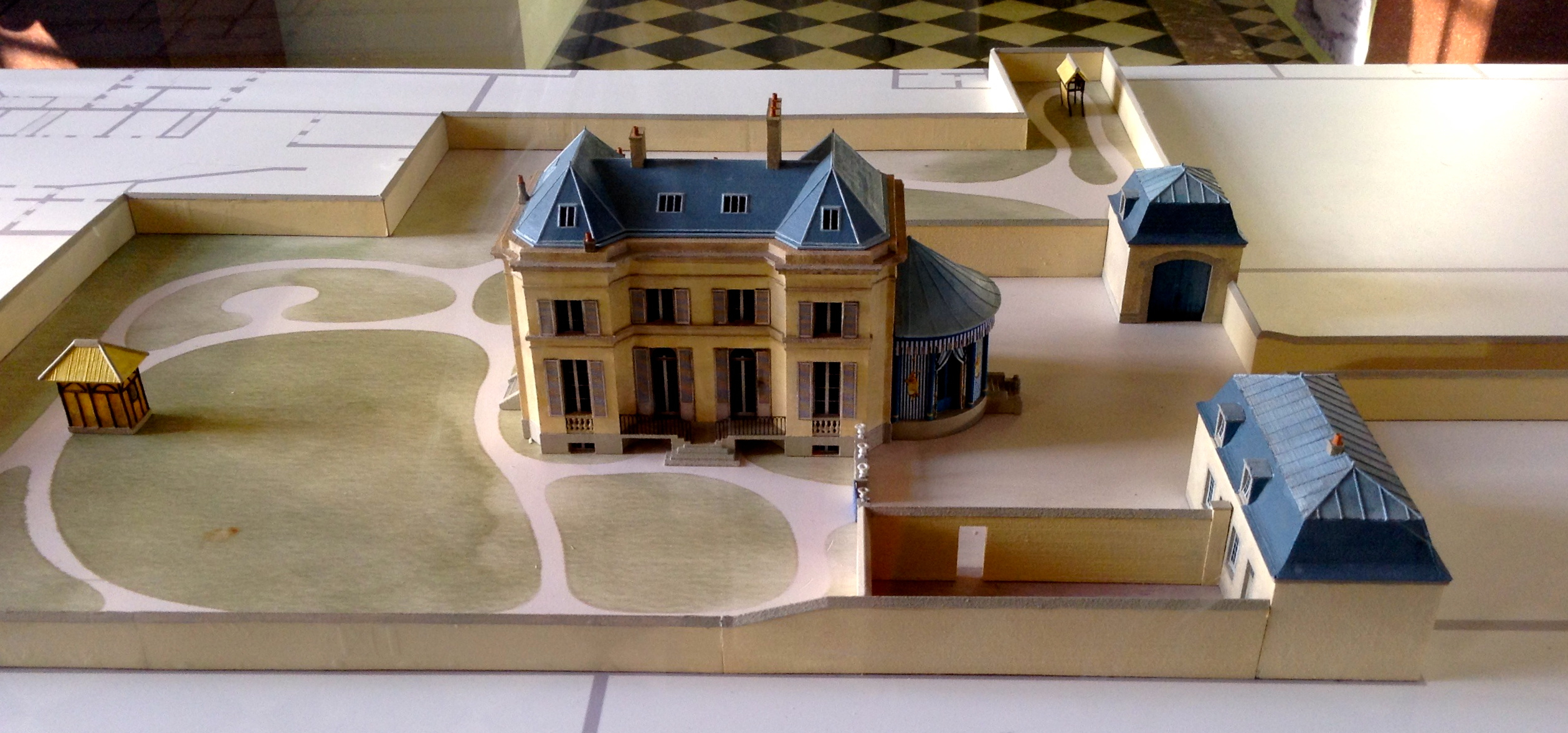

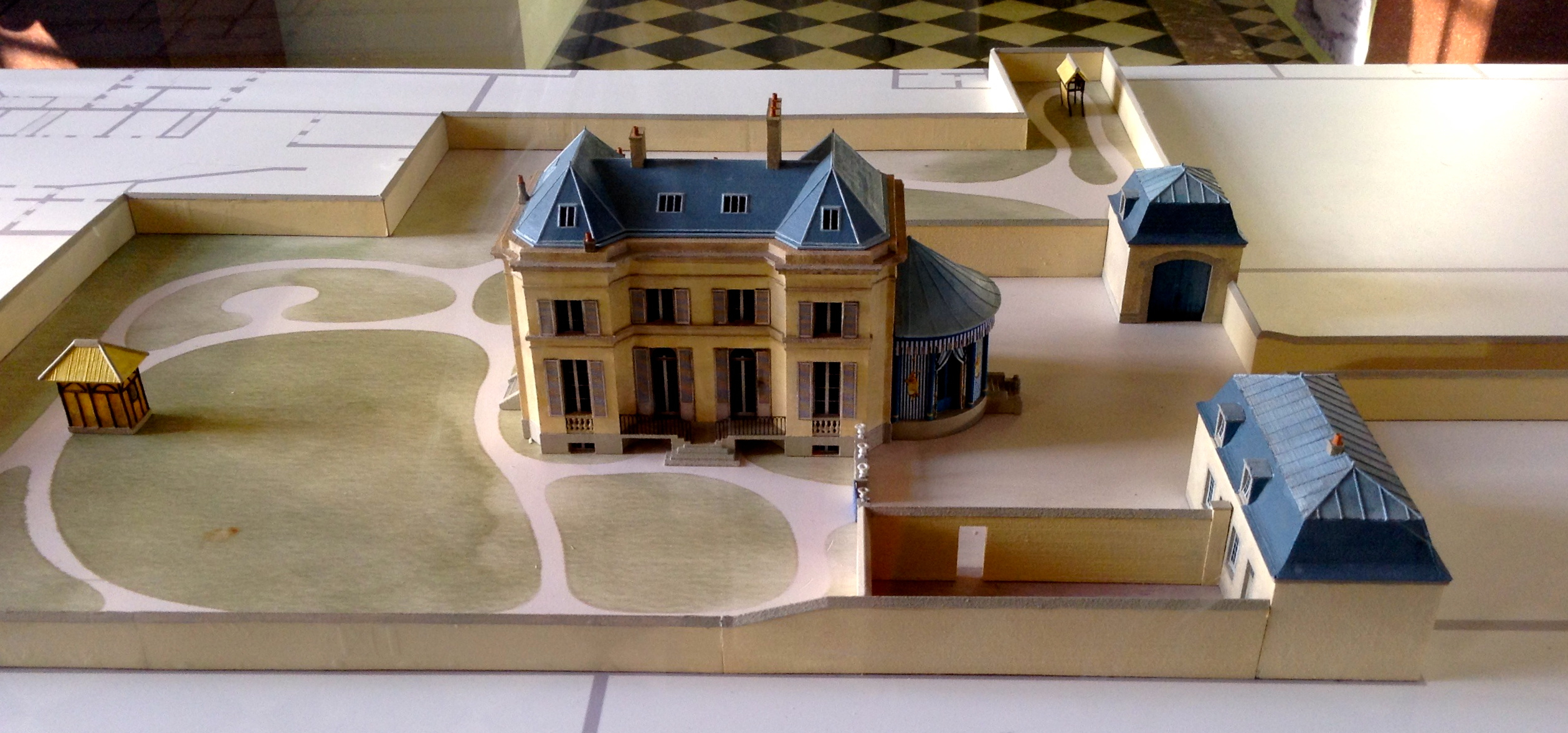

While researching The Game of Hope, intrepid traveller and fellow Francophil Ann Coombs sent me photos she took at a special exhibition at Malmaison. This was the one that took my breath away:

It’s a mock-up of the house Josephine rented before she met Napoleon, then on Rue Chantereine. After his victories in Italy, the street was renamed Rue de la Victoire, and Josephine had the house decorated in a military theme, a style she used again years later at Malmaison.

The tented entry is very like the one she added to Malmaison:

I thought Josephine made the tented addition to the house after marrying Napoleon, but according to “The House on the Rue de la Victorie” by Ira Grossman, she did this before she’d even met Napoleon. “She turned the terrace of the house into a veranda under a wooden tent which was hung with cotton draperies and decorated with painted or carved flags and pennants.”

It was especially exciting to see a mock-up of Chantereine because there was so very little known about this house. In writing about Hortense, I had a more accurate sense of the place.

Click here to read more of what I’ve discovered about enchanting Chantereine.

See also: The House on the Rue de la Victoire.SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Feb 23, 2018 | Baroque Explorations |

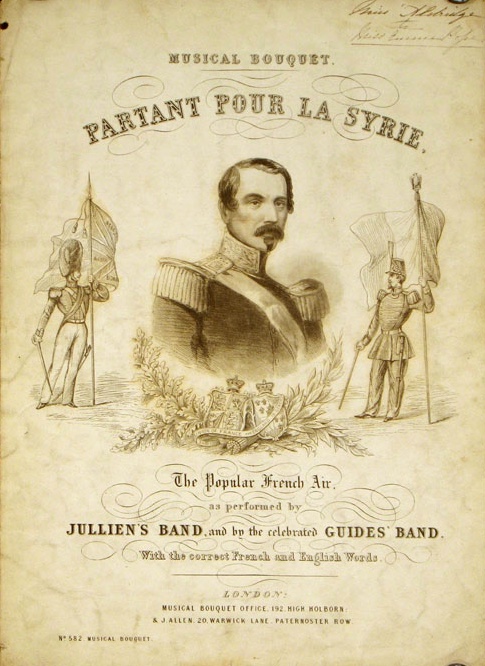

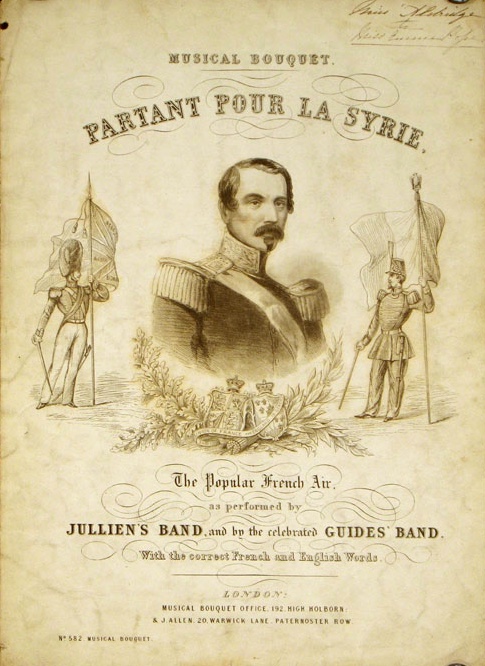

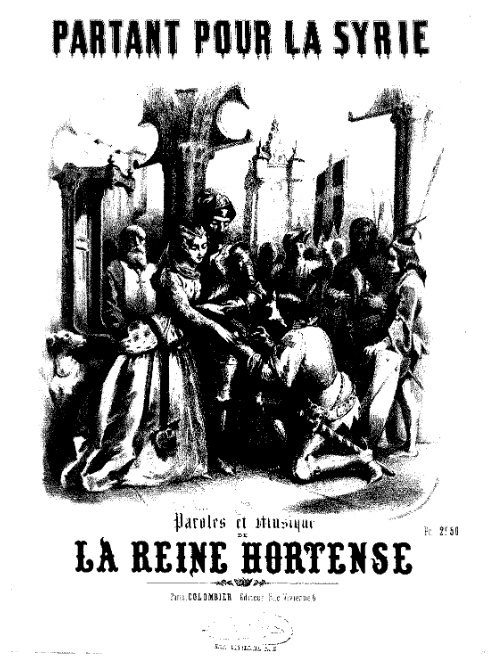

Hortense was an exceptionally creative person. At Madame Campan’s Institute she was fortunate to have Isabey for an art instructor and Jadin for music. Hortense painted and composed songs throughout her life, but she is most known for the song “Partant pour la Syrie,” which remains popular today. You can hear a lovely performance of this song here, by a singer wearing a gown very much like one Hortense might have worn.

Hortense’s creative process

How did this song come to be written? What was Hortense’s creative process? There are hints in something she wrote:

At Constance, I had few books and no collection of poems in which I could find words. I once made some verses for my brother; I tried to compose, but the obligation to find a rhyme, to confine myself to a measure, soon tired me and after a few bad verses, I was left to the music. (See the French original below.)

This gives us an idea about Hortense’s creative process: she would write melody, and search in books for the verse.

Partent pour la Syrie

She wrote that she wrote “Partent pour la Syrie” at Malmaison, while Josephine was playing tric-trac, an old form of backgammon. The date she composed it isn’t known. One theory is that Hortense wrote the melody, and that the words were created by Alexandre de Laborde in or about 1807.

Under the Restoration (when Napoleon was overthrown and monarchy restored), “Partent pour la Syrie” became the rallying song for those in support of Napoleon. Hortense’s son Napoleon III made it a national hymn.

Hortense as composer

As an adult, Hortense composed many songs, then called “Romances.”

You can “leaf” through this lovely book online: here.

A Constance, je n’avais que peu de livres et aucun recueil de poésies où je pusse trouver des paroles. J’avais fait autrefois quelques couplets pour mon frère; j’essayai d’en composer, mais l’obligation de trouver une rime, de me renfermer dans une mesure me fatigua bientôt et, après quelques mauvais vers, j’en restai à la musique.

—from “La reine Hortense et la musique” by Marie-Claude Chaudonneret in La Reine Hortense, Une femme artiste, a publication made for the 1993 exposition at Malmaison, France.

by Sandra Gulland | Apr 8, 2017 | Baroque Explorations |

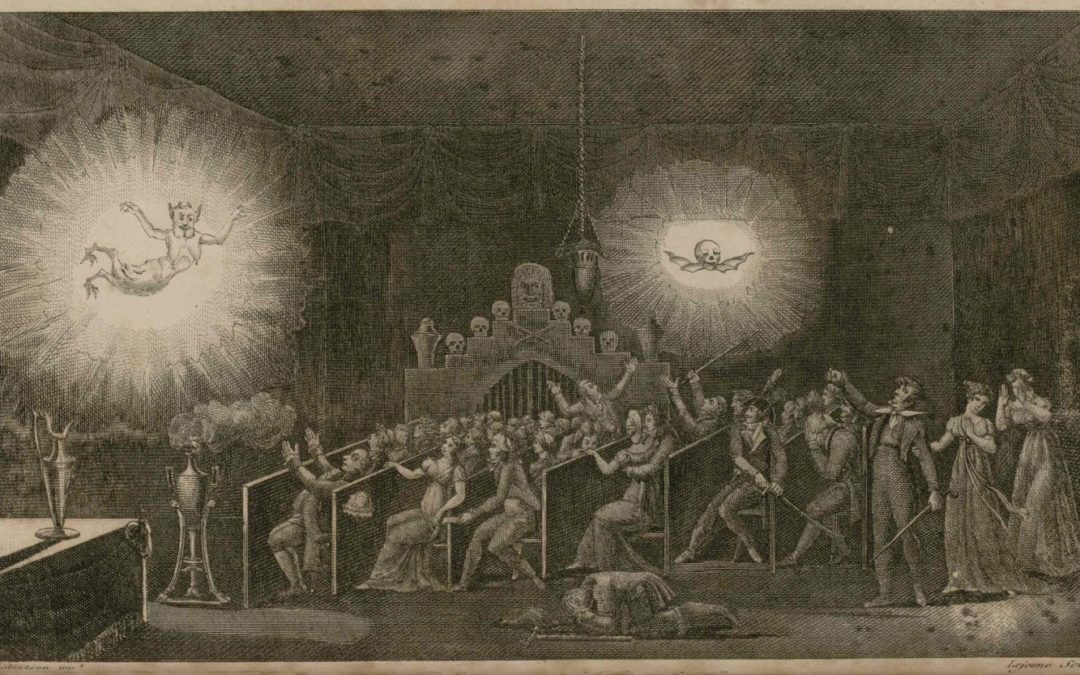

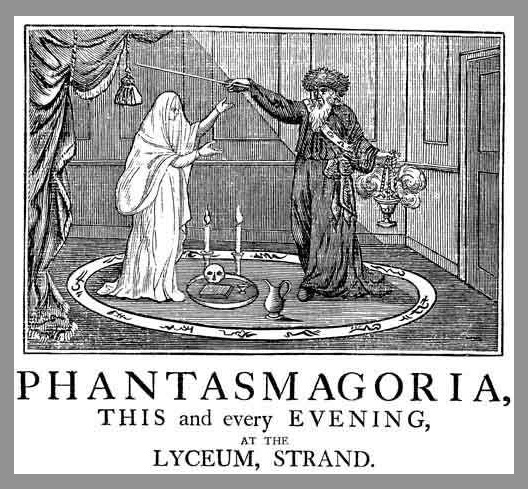

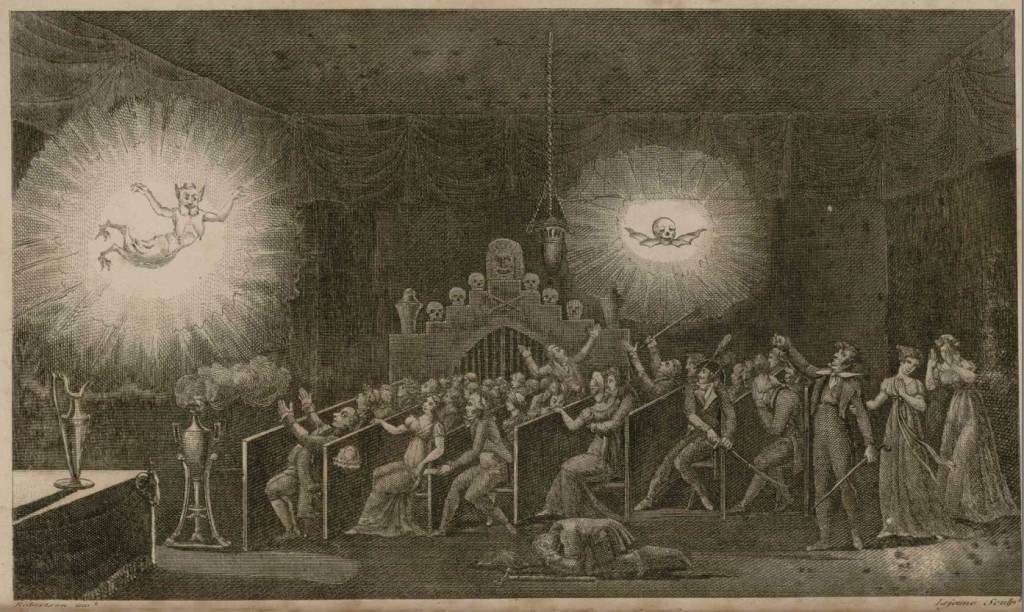

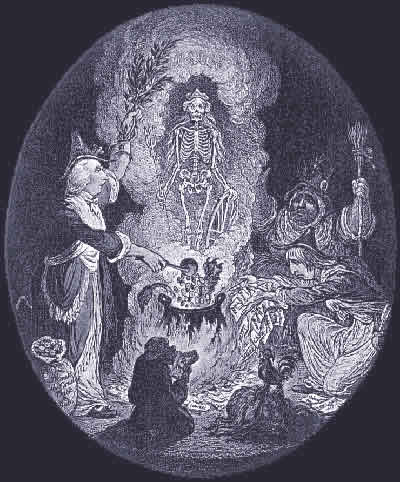

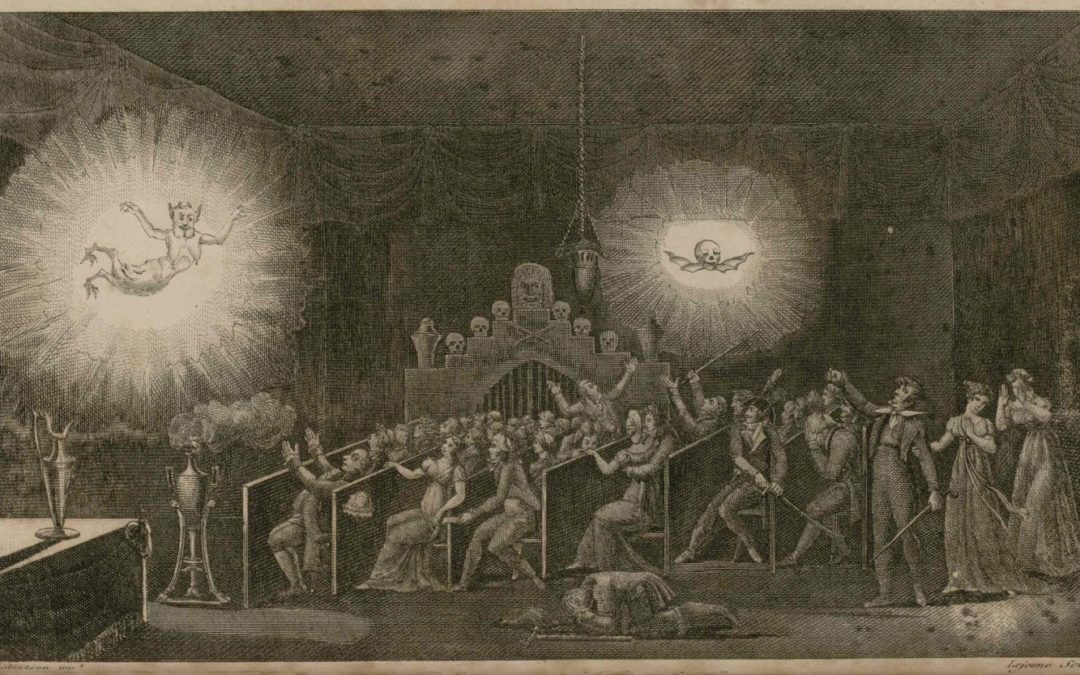

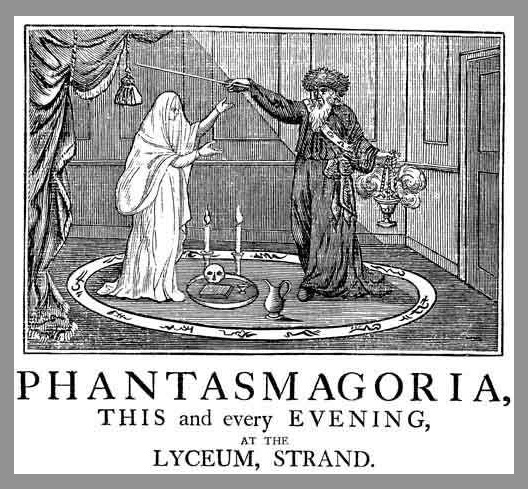

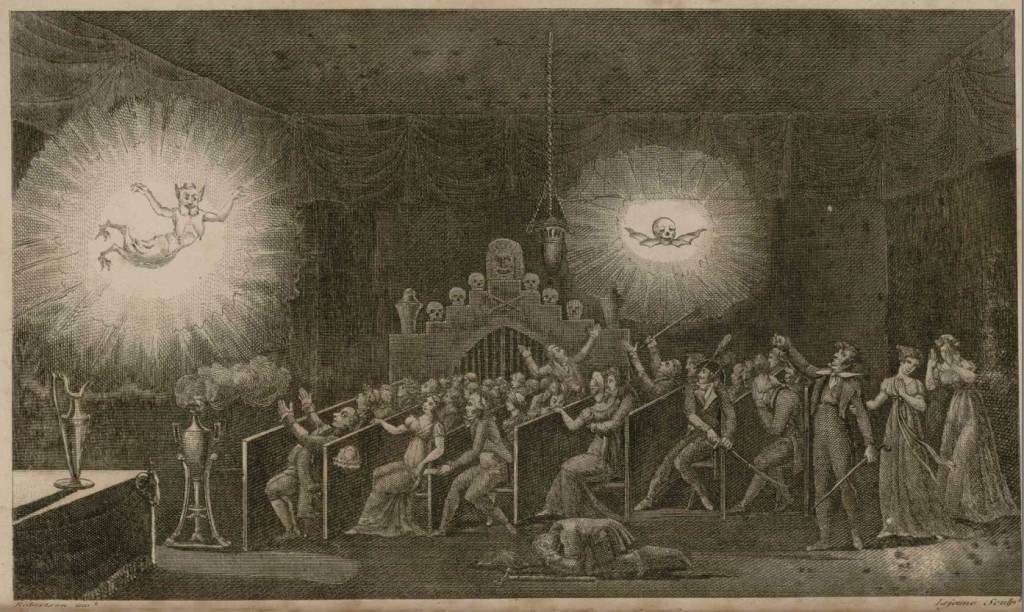

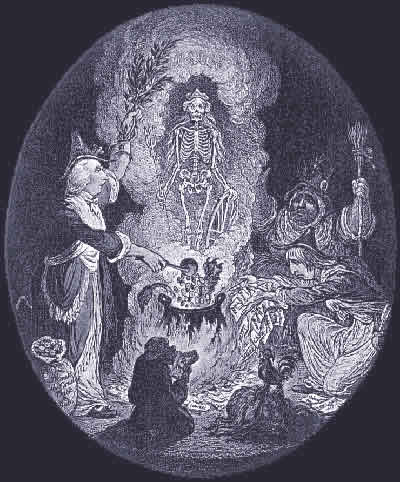

I have been doing quite a bit of research into Phantasmagorie for the Young Adult novel I’m writing about Josephine’s daughter Hortense.

Phantasmagoria was an extremely popular “show” put on for both children and adults in France after the French Revolution, featuring the appearance of ghouls, ghosts, spectres and apparitions.

It was shown in other countries of Europe, but it was by far most popular in France, where so many had lost loved ones during the Terror, and where, apparently, a hunger for contact with the afterlife was strong.

Etienne-Gaspard Robertson (1763 – 1837) was the mastermind behind these productions. His first French exhibition of “Fantasmagorie” was at the Pavillon de l’Echiquier in Paris. He later staged it in the abandoned chapel of a Capuchin monastery near the Palace Vendome.

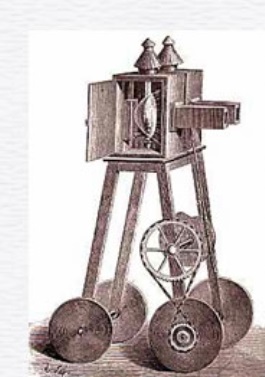

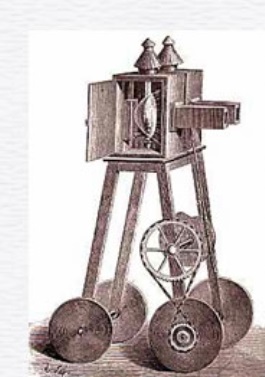

Robertson devised a double-lens lantern on wheels to create his ghostly effect, an invention which is considered the predecessor of the motion-picture camera. (In 1799 he got a patent for this camera, calling it a Fantoscope.)

To create the shadow play, Robertson used smoke, huge sheets of glass, mirrors, and several mobile lanterns. He would project from below the stage, and the hidden movement of a lantern created the illusion of motion. He would change the position of the lens to show a figure growing larger (and apparently closer), yet remaining in sharp focus. He also used rear projection, and projection onto gauze coated with wax, ironed to give a translucent appearance.

The purpose of the show was to terrify the audience—and it succeeded. It could well be considered the forefather of today’s horror movie.

Much of this information is from The History of the Discovery of Cinematography by Paul Burns, which unfortunately is not available on-line at this time.

For excellent documents, see The Richard Balzer Collection.

For a bibliography of books related to the history of cinematography, click this link.

For a full programme: Fantasmagorie de Robertson, Cour des Capucines, près la place Vendôme.

Robertson describes some of his phantasmagoria in his Mémoires.

(Phantasmagoria is not to be confused, by the way, with the 1995 interactive video game: Phantasmagoria!)

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Nov 22, 2016 | Baroque Explorations, Mistress of the Sun, Resources for Readers |

As I’ve no doubt mentioned before, I’m a big fan of Renaissance magazine. I devour every issue as soon as it arrives. It’s largely intended for devotees of living history, specifically those who participate in Renaissance fairs. That aspect of the publication doesn’t appeal to me, but their historical background and news items are fantastic. I end up tucking at least one article per issue into a research database (by photographing and emailing it to Evernote).

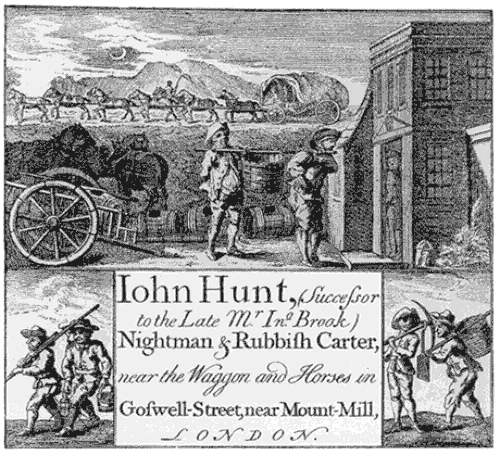

I dog-eared two articles in the April/May 2013 issue: one on the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum in England (drool, some day I hope to go), and the other on that most secretive of topics—the privy.

I was taken aback by this remark by a travelling Italian priest in 1518:

“Whereas in Germany there are one or two tin chamber pots to every bed (in Flanders they are made of brass and very clean), in France for want of any alternative, one has to urinate on the fire. They do this everywhere, by night and day, and indeed, the greater the nobleman or lord, the more readily or openly he will do it.”

I’d read of this practice — I have such a scene in my last novel, Mistress of the Sun, when a child is overtaken with the need to relieve herself — but frankly, I didn’t think it so commonplace.

The French, in turn, are reported to have been horrified by the British habit of men relieving themselves at the dining table:

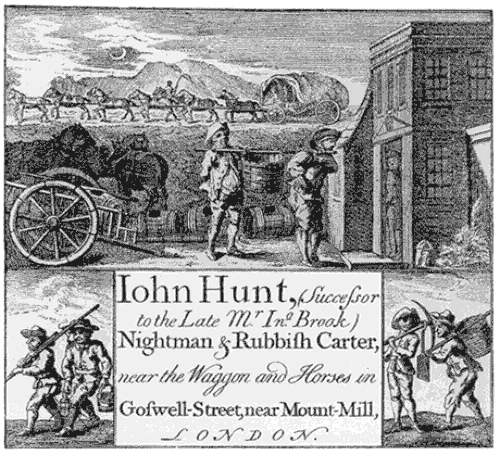

English gentlemen, known for their prodigious drinking habits, were wont to relieve themselves where they were – in the dining room, for instance, or in a common room of a public inn – where they did not always aim straight and true (as the young man at left), much to the chagrin and disbelief of French travelers, some of whom wrote about this unsanitary habit. (As reported in a review of the book Privies and Water Closets by David J. Eveleigh on the excellent blog, Jane Austen’s World.)

Some details from the Renaissance magazine article that may show up in one of my novels:

“Night men”—who cleaned out the cesspits—were well paid, as much as skilled tradesmen.

Refreshing a privy with juniper.

One sometimes sees images of several privy holes all in a row. I have a friend who restored a house in Mexico, formerly a monastery. What’s now their breakfast nook was once a three-hole privy. I suspect this was a social time. (Let’s see this in fiction!)

Of course people would build their privy over a river or stream, but what to do in town? Some built a privy on a sort of bridge connecting two houses, emptying into an alley. (Gross.)

The wealthy, of course, often had more elegant solutions …

… when they weren’t using the fireplace, that is. ;-(

Coincidently, just this week there is a post on this subject — “Secrets of a Roman Sewer” — on the wonderful historical blog Wonders & Marvels. There is a great deal to be learned from “poo,” but I’ll leave it at that.

I know this subject seems like an unpleasant diversion from writing about a glamorous Hoyden or Firebrand, but when writing about such a person in fiction, one rather needs to know! As well, I confess: my husband and I had an outdoor privy when we moved to our log cabin in the country, decades ago. I think of it with great affection. As a mother of toddlers, I would enjoy a quiet minute or two on what my own characters refer to as “the necessary.”

by Sandra Gulland | Apr 1, 2016 | Baroque Explorations |

What is the history of April Fools’ Day?

A reference to April Fools’ Day pranks has been found as early as 1539, in a comical poem by Flemish writer Eduard De Dene. Over a century later, in 1686, John Aubrey of England noted “Fooles holy day” observed on April 1st. At the end of the century, a British newspaper noted a popular April Fools’ Day prank: sending people to the Tower of London to see the lions washed.

In general, it seems that April Fools’ Day originated in Northern Europe and migrated to England. There are a number of theories on how this came about, but few conclusions.

The calendar-change theory

Traditionally, the French used Easter as the start of the year. In 1563, the French King Charles IX declared January 1 to be the New Year. According to legend, those who kept to the old calendar and celebrated the New Year in the spring had jokes played on them. Pranksters would surreptitiously stick paper fish to their backs. The victims of this prank were thus called Poisson d’Avril, or April Fish, which is still the French term for an April Fool.

The French calendar-change theory is tidy, but for the fact that the switch to January 1 to mark the New Year happened very slowly over a century.

The abundance-of-fish theory

Another French theory traces the origin of April Fools’ Day to the abundance of fish to be found in during early April when fish have hatched. These young fish were easily fooled with a hook and lure. The French called them Poisson d’Avril, or April Fish. Soon it became customary (according to this theory) to fool people on April 1, as a way of celebrating the abundance of foolish fish.

The Roman tradition theory

In 1766, this note was published in Gentleman’s Magazine in England:

The strange custom prevalent throughout this kingdom, of people making fools of one another upon the first of April, arose from the year formerly beginning, as to some purpose, and in some respects, on the twenty-fifth of March, which was supposed to be the incarnation of our Lord; it being customary with the Romans, as well as with us, to hold a festival, attended by an octave, at the commencement of the new year—which festival lasted for eight days, whereof the first and last were the principal; therefore the first of April is the octave of the twenty-fifth of March, and, consequently, the close or ending of the feast, which was both the festival of the Annunciation and the beginning of the new year.”

I think this is a credible explanation.

The renewal-ritual theory

Nearly every culture has a festival to celebrate the end of winter and the return of spring. Anthropologists call these “renewal festivals” and they often they involve mayhem and the wearing of disguises.

Might April Fools’ Day be the last vestiges of a pagan renewal festival?

The custom of playing practical jokes on friends was part of the celebrations in ancient Rome on March 25 (Hilaria) and in India on March 31 (Huli). The timing seems related to the vernal equinox and the coming of spring — a time when nature fools us with sudden changes between showers and sunshine.

Certainly we are often fooled by hints of spring!

For an excellent article on these puzzles, click here.