.

I usually become huffy when people condemn Louis XIV for acting so strongly against his Minister of Finance, Nicholas Foucquet (often spelled Fouquet), arresting and ultimately imprisoning him for life. My understanding was that the evidence against him had been building for some time:

that he had been dipping liberally into France’s funds for his personal use;

that he was running a spy operation with paid informants;

that he was building up an armed force;

that he aspired to wear the crown.

All this justified, in my view, Louis’s strong actions. Now, after reading The Man Who Outshone the Sun King: Ambition, Triumph and Treachery in the Reign of Louis XIV by Charles Drazin, I’m not so sure.

This is an excellent book, focusing very much on Foucquet’s side of the story. I found it so absorbing I stayed up too late many a night reading it.

This is an excellent book, focusing very much on Foucquet’s side of the story. I found it so absorbing I stayed up too late many a night reading it.

Foucquet’s life story is fascinating. First, there’s his family: his ethical and highly-religious father and mother. His mother, especially, who was a tireless healer, who created herbal remedies, and went into the putrid corridors of the hospitals to help cure.

(As Nicholas Foucquet was being tried for embezzlement and treason, his eldest daughter gave one of her grandmother’s remedies to the Queen-mother to pass on to the young Queen, who was feared to be dying after a difficult childbirth. The curative effect was immediate and the Queen-mother declared Madame Foucquet a saint. The poignancy of these stories! Everyone was related, everyone a friend, everyone an enemy.)

And then there are Foucquet’s brothers: fearless Basile who ran countless risks, running the Court’s messages through enemy lines; young, art-obsessed Louis, who Nicholas sent to Rome to buy paintings for him. Hesitant at first, Louis became so confident and enthusiastic about his task that Nicholas had to cry “Stop!” as cartload after cartload of antique treasures arrived.

And then there are the men Nicholas discovered, the men he hired, men I would have respected and admired: his talented, academic secretary Pellison (who discovered La Fontaine for him); his team at Vaux–le–Vicomte, Charles Le Brun, André Le Nôtre, Le Vau (all of whom would be hired by the King to create Versailles).

And let us not forget Nicholas’s second wife, Marie-Madeleine, a model of courage, evading the spies and police as she secretly moved from one underground printing press to another, printing tracts defending her husband, and ultimately moving into the prison with him for a period of time.

And then, of course, there is Nicholas himself, a very bright spark, an exceptionally decisive and hard-working man (driven, in fact), a sensitive negotiator and diplomat, an intellectual with a restless, inquiring imagination, and (this is key) an essentially ethical and honest man.

And so: what happened?

I’m not sure it was power Nicholas Foucquet was seeking. His weakness, if anything, seems to have been for artistic beauty, for the rare and exquisite. I suspect his chateaux, Vaux–le–Vicomte, became an obsession for him, his artistic creation … and certainly a money-drain. He did show an occasional flash of anger, of entitlement, and given how much he did in fact sacrifice for France, one could see how he felt owed.

But embezzlement is one thing, and treason quite another. On this Drazin leaves me a little unfulfilled. I’m not convinced he has turned over all the rocks.

The turning point in Foucquet’s life, I suspect, was in 1658, when he got dangerously ill with a fever. Thereafter, he had spells of serious sickness. Certainly, he would have felt, then, that his days were numbered. He became, it seems, unbalanced, paranoid, writing what seems to me a feverishly detailed fantasy-plan of what each member of his family were to do if he were arrested. (I would have liked Drazin to have addressed the subject of Foucquet’s health a bit more; I think it may have been key.)

Overall, this is an excellent book. It opened my eyes, yet even so, it failed to completely convince me of Foucquet’s ultimate innocence. I can’t help but feel that the author is suppressing, or at the least not addressing the negatives. Was Foucquet a womanizer? How extensive was his spy operation? What was its purpose? How was it that his mother and his brother Basile came to condemn him so harshly?

What I do come away with is the feeling that Louis XIV was far too harsh. Was Foucquet so dangerous that he couldn’t be simply exiled? What was his crime? I also look at Colbert a little more skeptically now (and I’ve been a Colbert fan).

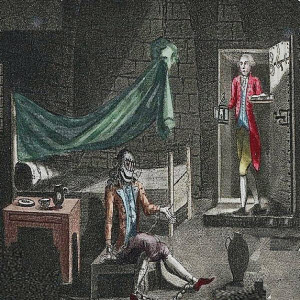

At the end of any account of Nicholas Foucquet, there is the mystery of the “Man in the Iron Mask“, a man who was jailed in the same prison ? a man who knew something so threatening to the King that he was to be threatened with death if he talked of anything but his most basic daily needs, a man to be kept in the strictest isolation, a man who was allowed, eventually, to speak to one man, and one man only in the prison: to Nicholas Foucquet, in the capacity of his valet. Drazin concludes, then, that Foucquet must have already known this man’s secret.

If only we could know what that secret was!

Great post, Sandra! In The Dream of a King, Fouquet is certainly given his due for his unwitting contribution to the glories of Versailles.

This book seems a fascinating read, but I don't buy the theory Fouquet's innocence either. The connection with the Iron Mask is certainly troubling and hints at something more sinister than embezzlement. Those were clearly men who would never see the light of day again…

I love this post Sandra…got me soo curious to read the book. I too, though, can't help huffing up if I hear anything that wrongly accuses the Sun King. Thanks:)