by Sandra Gulland | Nov 25, 2018 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, Painting, Work in Process (WIP) |

Yesterday I began searching for my next raptor to paint and I was captured by this lady, named, appropriately, “Imperious.”

I wanted to find out the breed of this bird and to know if it might be one my character in The Next Novel might have had experience with. In other words, what was this bird, and was it common to Elizabethan England?

I’d discovered Imperious on the website of Raphael Historical Falconry, and so I wrote to them. This morning, I had a long email from Emma Raphael, giving me a full and very interesting explanation. (People are so very generous with their knowledge!) Imperious is a Golden Eagle hybrid, and Eagles were rarely seen in Elizabethan England. In fact, there was only one recorded, in the ruins of an old castle near Chester, and was persecuted by farmers who feared for their young cattle.

I’d discovered Imperious on the website of Raphael Historical Falconry, and so I wrote to them. This morning, I had a long email from Emma Raphael, giving me a full and very interesting explanation. (People are so very generous with their knowledge!) Imperious is a Golden Eagle hybrid, and Eagles were rarely seen in Elizabethan England. In fact, there was only one recorded, in the ruins of an old castle near Chester, and was persecuted by farmers who feared for their young cattle.

The beauty of the Red Kite

The wild raptor most associated with Elizabethan England, Emma went on to explain, is the Red Kite.

The red kite might be a scavenger raptor, but it is so beautiful! I believe I may have found my next painting subject. (Note: I did!)

Emma went on to explain about red kites in Elizabethan England:

They were at their highest population levels ever at this time because of the spread of human settlements and all the open rubbish pits found in towns and villages in which they scavenged. They flocked in their hundreds and could be seen wheeling around the skies like crows whistling and calling.

She suggested I look at the painting “The Wedding at Bermondsey” — a painting of a wedding in Elizabethan London. From a detail of the painting, red kites can be seen in the sky.

Emma goes on to explain that …

The royals throughout the period hunted kites with Gyr Falcons because they were so numerous and there are lots of accounts of “kite hawking” in Londonshire, Cambridgeshire and Huntingtonshire.

Cambridgeshire is the initial location of The Next Novel, and so here, with a simple inquiry about Imperious, I have a wealth of scene possibilities.

The charm of men in bloomers

Additionally, ” Wedding at Bermondsey” is a painting I could get absorbed in for some time. The details are delicious. The 16th century is new to me, and I confess that men in bloomers are charmingly captivating.

Belgium artist Joris Hoefnagel painted “Wedding at Bermondsey” some time after his visit to the UK in 1569.

by Sandra Gulland | Nov 22, 2016 | Baroque Explorations, Mistress of the Sun, Resources for Readers |

As I’ve no doubt mentioned before, I’m a big fan of Renaissance magazine. I devour every issue as soon as it arrives. It’s largely intended for devotees of living history, specifically those who participate in Renaissance fairs. That aspect of the publication doesn’t appeal to me, but their historical background and news items are fantastic. I end up tucking at least one article per issue into a research database (by photographing and emailing it to Evernote).

I dog-eared two articles in the April/May 2013 issue: one on the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum in England (drool, some day I hope to go), and the other on that most secretive of topics—the privy.

I was taken aback by this remark by a travelling Italian priest in 1518:

“Whereas in Germany there are one or two tin chamber pots to every bed (in Flanders they are made of brass and very clean), in France for want of any alternative, one has to urinate on the fire. They do this everywhere, by night and day, and indeed, the greater the nobleman or lord, the more readily or openly he will do it.”

I’d read of this practice — I have such a scene in my last novel, Mistress of the Sun, when a child is overtaken with the need to relieve herself — but frankly, I didn’t think it so commonplace.

The French, in turn, are reported to have been horrified by the British habit of men relieving themselves at the dining table:

English gentlemen, known for their prodigious drinking habits, were wont to relieve themselves where they were – in the dining room, for instance, or in a common room of a public inn – where they did not always aim straight and true (as the young man at left), much to the chagrin and disbelief of French travelers, some of whom wrote about this unsanitary habit. (As reported in a review of the book Privies and Water Closets by David J. Eveleigh on the excellent blog, Jane Austen’s World.)

Some details from the Renaissance magazine article that may show up in one of my novels:

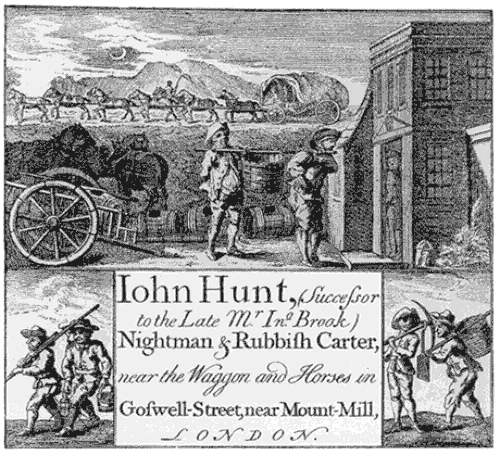

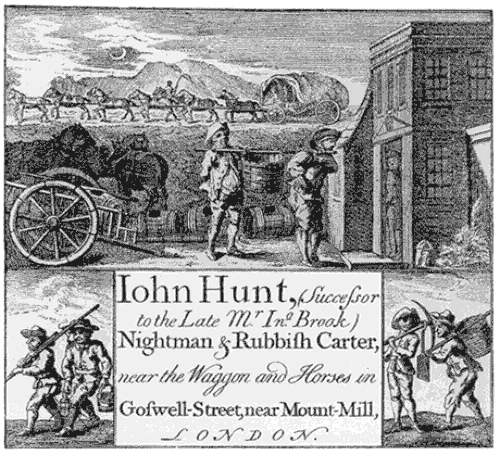

“Night men”—who cleaned out the cesspits—were well paid, as much as skilled tradesmen.

Refreshing a privy with juniper.

One sometimes sees images of several privy holes all in a row. I have a friend who restored a house in Mexico, formerly a monastery. What’s now their breakfast nook was once a three-hole privy. I suspect this was a social time. (Let’s see this in fiction!)

Of course people would build their privy over a river or stream, but what to do in town? Some built a privy on a sort of bridge connecting two houses, emptying into an alley. (Gross.)

The wealthy, of course, often had more elegant solutions …

… when they weren’t using the fireplace, that is. ;-(

Coincidently, just this week there is a post on this subject — “Secrets of a Roman Sewer” — on the wonderful historical blog Wonders & Marvels. There is a great deal to be learned from “poo,” but I’ll leave it at that.

I know this subject seems like an unpleasant diversion from writing about a glamorous Hoyden or Firebrand, but when writing about such a person in fiction, one rather needs to know! As well, I confess: my husband and I had an outdoor privy when we moved to our log cabin in the country, decades ago. I think of it with great affection. As a mother of toddlers, I would enjoy a quiet minute or two on what my own characters refer to as “the necessary.”

I’d discovered Imperious on the website of Raphael Historical Falconry, and so I wrote to them. This morning, I had a long email from Emma Raphael, giving me a full and very interesting explanation. (People are so very generous with their knowledge!) Imperious is a Golden Eagle hybrid, and Eagles were rarely seen in Elizabethan England. In fact, there was only one recorded, in the ruins of an old castle near Chester, and was persecuted by farmers who feared for their young cattle.

I’d discovered Imperious on the website of Raphael Historical Falconry, and so I wrote to them. This morning, I had a long email from Emma Raphael, giving me a full and very interesting explanation. (People are so very generous with their knowledge!) Imperious is a Golden Eagle hybrid, and Eagles were rarely seen in Elizabethan England. In fact, there was only one recorded, in the ruins of an old castle near Chester, and was persecuted by farmers who feared for their young cattle.