by Sandra Gulland | Oct 31, 2020 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I recently read an article by the elusive Ryan Holiday, a professional book researcher. He made one very important point—at least to me. He said that the first step in researching is to acquire a research library which will include books that you will likely never read. He calls it an anti-library.

We all have books and papers that we haven’t read yet. Instead of feeling guilty, you should see them as an opportunity: know they’re available to you if you ever need them.

This is exactly what I do: buy too many books, print out too many articles, and read only a fraction of them. So now I’m going to stop feeling guilty about it.

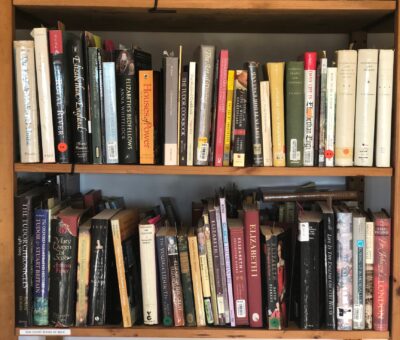

Two of six shelves for the WIP. Note the white tag in the lower left. It reads: “Sun Court books at the back.” In other words, I’ve run out of shelf space.

One of my rules as a reader is to read one book mentioned in or cited in every book that I read.

I often scour footnotes for references to books the author has relied on. Lately, I’ve acquired two books in this way and they have proved to be invaluable.

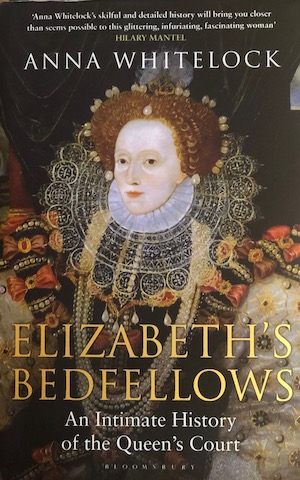

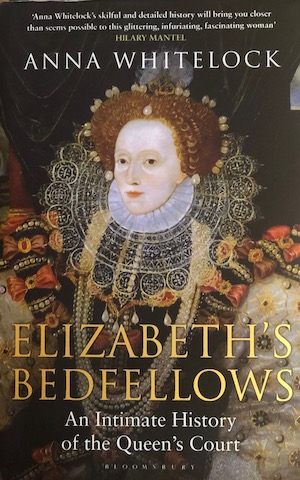

One is Elizabeth’s Bedfellows; An Intimate History of the Queen’s Court by British historian Anna Whitelock. She was one of the experts on a documentary on Elizabeth I. I ordered her book and immediately on opening it saw details I badly needed to write a scene that had me stumped. I will only need a few chapters of this book—at least for this WIP—but they are gold to me.

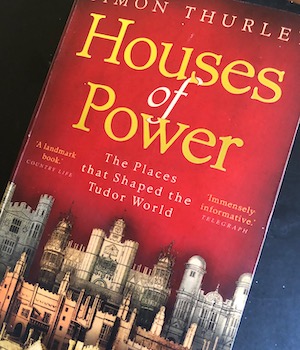

The other book is a paperback edition of Houses of Power; The Places the Shaped the Tudor World by Simon Thurley. (Note that this book can be hard to find, at least in North America. I finally found a used copy on Abebook.com.)

I have a number of works by this wonderful historian, but this is the book that made me gasp. It’s full of the floorplans of Tudor palaces at that time, and amazing details as well. In no time flat, I began to mark it up.

A research trick I use: for a print book I own, if the “search me” feature is available on Amazon, I will add it to a list. Say I’m looking for events in 1553: I’ll search for that year in the Amazon link of the book—note that it has to be the print edition—and this will give me the pages to go to in my copy of the book. It’s an instant index to the type of thing that would never show up in an official index.

Since posting this, I’ve had the pleasure of listening to a podcast interview of Professor Simon Thurley on The Tudor Travel Show. Fascinating! He also has two free online lectures I’m looking forward to listening to: Tudor Ambition; Houses of the Boleyn Family and Ruling Passions: The Architecture of the Cecils. As well, he has launched an invaluable research website that provides up-to-date information on royal palaces: RoyalPalaces.com.

Dr. Sarah Morris of The Tudor Travel Show (above) is an invaluable source of information, both through her Tudor Travel videos and podcasts, but also through her writing: her two novels about Anne Boleyn—Le Temps Viendra (I and II)—as well as the abundantly detailed non-fiction account In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, written together with On the Tudor Trail podcaster Natalie Grueninger.

The art at the top is from Bibliodessy.

by Sandra Gulland | Sep 19, 2020 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, Resources for Writers, The Writing Process, Tudor England, Work in Process (WIP) |

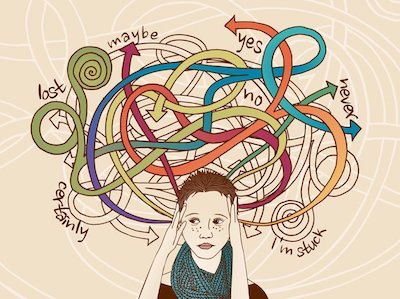

I’ve been stuck for nearly a week over a chapter in the WIP. (The whip, I think ruefully, as I type those letters.) The problem has many causes. One is that I have a stubborn need to know where-the-heck my heroine (Elizabeth Tudor, in this instance) is, in fact. It’s a period of only two days, and historians don’t provide the details—which should lead me to suspect that the information simply isn’t available.

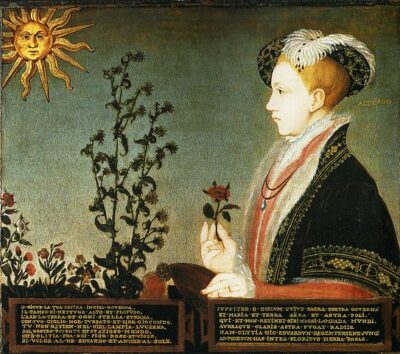

Edward VI with flowers by William Scrots, circa 1550

It’s an important moment, so I’m surprised not more is known. Fifteen-year-old King Eddie VI has died, and (after something of a bloodless battle) his half-sister Mary has been proclaimed queen.

Portrait of Queen Mary I of England by Antonis Mor, 1554.

Mary’s much younger half-sister Elizabeth (not yet twenty), is now the heir to the throne. She is riding out to meet Mary—to bow before her sister queen.

Elizabeth, a good ten years later.

First, the frazzled timeline

This is what is said:

On Friday, July 28, 1553, news of her sister Mary’s accession reaches Elizabeth at Hatfield. (Tudors—Twenty-eight Days to Wanstead by Alan Cornish)

This website account is fantastic, but this one date is unlikely, in my view, because Mary was proclaimed queen in London on July 19.

According to historian Tracy Borman in Elizabeth’s Women (page 136), Elizabeth wrote Mary on that day to congratulate her, but also …

Showing all due deference, she also humbly craved Mary’s advice as to whether she ought to appear in mourning clothes out of respect for their brother, Edward, or something more festive.

(This is the type of detail I relish.)

It would have taken time for Elizabeth’s missive to reach Mary, for she was in the northeast, at her Framlingham castle, already attending to matters of state business and debating whether or not to go to London. Some advised her that it would be wise to return soon while the public was so enthusiastic about her. On the negative side, it was stinking hot in London and there were rumours of plague.

Mary was apparently prepared to be magnanimous in her triumph. She therefore invited Elizabeth to accompany her to London. (Borman’s Elizabeth’s Women)

Mary set out for London on Monday, July 24. It was a long journey: Ipswich (two nights), Colchester (one night), Newhall (three nights), Ingatestone (two nights), Havering (one night), finally arriving at Wanstead House on Tuesday, August 1, where she welcomed Elisabeth the next day, on August 2. (This overnight stay is rarely mentioned in biographies.) Together they set out for London on Thursday, August 3—with a combined entourage of over twenty thousand—arriving late that afternoon in London.

Elizabeth set out to meet Mary on Saturday, July 29, and by most accounts, she stayed for only one night in London before heading out the next day, Sunday, July 30, to meet Mary.

The puzzle

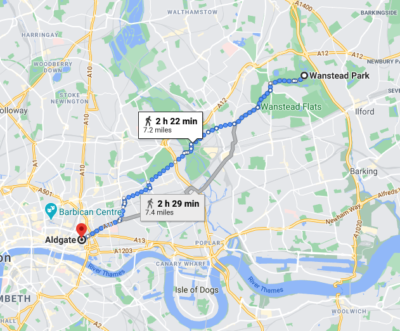

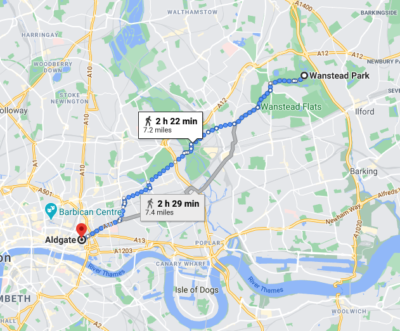

The journey from the London gate to Wanstead takes but a few hours on foot. (See my note below.) If Elizabeth was in London on July 29 for only one night, and met Mary on August 2 near Wanstead, where was she on July 31 and August 1? She was travelling with an entourage of over a thousand, so it was not as if she could drop in just anywhere.

This question foolishly cost me several days of work. I finally found support for the likelihood that Elizabeth had simply stayed at Somerset House, her new (to her) manor in London, for the full three nights. (Elizabeth I; The Word of a Prince, by Maria Perry, page 83.)

Second, the frazzled meet-up

A few historians state that Elizabeth stayed with Mary for one night at Wanstead House, and the consensus seems to be that they met on the road, and that Elizabeth dismounted and knelt in the dirt before Mary.

The problem with writing fact-based fiction — at least for me — is that things have to make sense. So now my question was: If Mary was expecting Elizabeth at Wanstead House, why did she meet her on the road? I didn’t want to spend another week on this, so I decided to sketch out a draft where they meet on the road, Elizabeth kneels, and they move on to Wanstead House from there.

But then what?

However Elizabeth and Mary meet, the sheer size of their entourages boggled my mind. Elizabeth had an entourage of over a thousand, but it was nothing to compare with her sister’s following. Imagine:

In the late afternoon of 3 August, Mary Tudor set out in procession from Wanstead to take possession of her kingdom. Those who stood along the processional route to London were astounded by the great number in her party. Mary had an escort of some ten thousand people with her – ‘gentlemen, squires, knights and lords’, and not to mention, the various peeresses, clergymen, judges, heralds, and foreign dignitaries come to pay her tribute.

—The Turbulent Crown: The Story of the Tudor Queens by Roland Hui (p. 322).

This is an image of the coronation procession of Elizabeth’s brother, King Edward VI. Imagine the traffic congestion!

This was at a hot time of year: the dust clouds of Mary’s procession coming through rural Essex must have been horrendous.

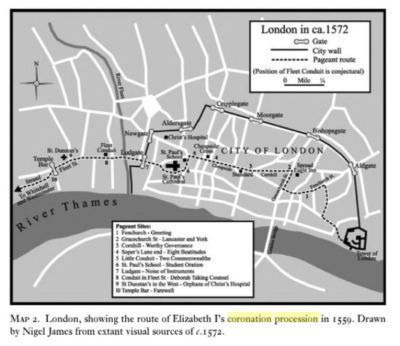

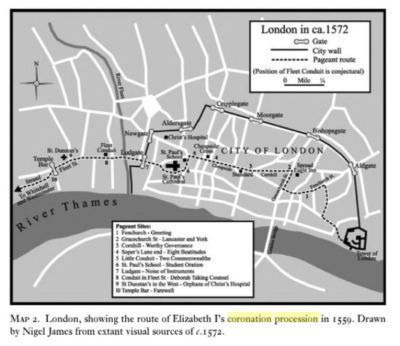

It did not take long to run into another time-consuming research question: Once they reach London, followed by well over ten thousand, what route do they take to the Tower of London? I decided that one hint might be to find out what the traditional route for a regal procession to or from the Tower of London might have been. This (eventually) led me to an amazing book (in four volumes): The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth by John Nichols on https://books.google.ca. On page 115 of Volume 1, there is this map:

Knowing this, I was able to chart the route on the fabulous interactive Agas Map of Early Modern London: Entering at Aldgate, they would wend their way down Aldgate Street, take the left fork onto Fenchurch Street, left onto Mark Lane, right on Tower Street and right again on Petty Wales to the entry into the Tower.

To the Tower!

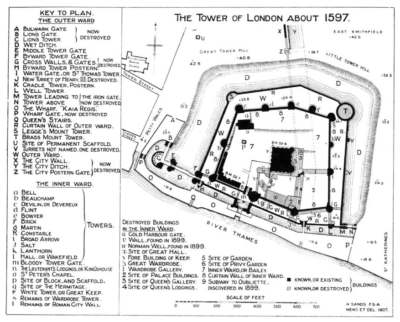

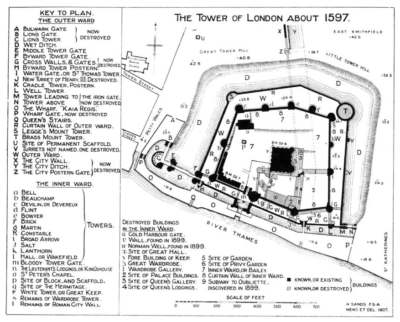

My second puzzle, also solved today, was to determine where were the queen’s apartments in the Tower of London. Several maps later, including the one below, I discovered that the queen’s apartments were in the lower right-hand corner of the Tower premises, fairly cut off from any unpleasantness.

For what queen’s apartments might have looked like, I found an excellent blog post on The Tudor Travel Guide: The Royal Apartments at the Tower & the Scandalous Killing of Anne Boleyn.

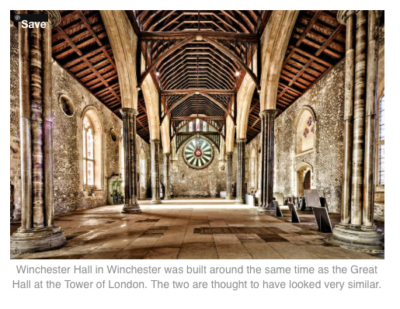

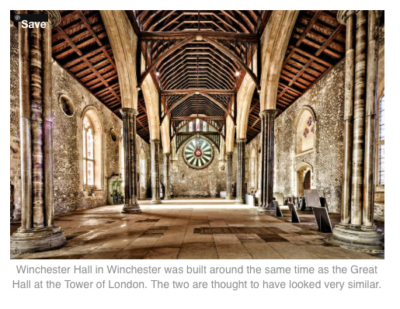

In addition to great details, the site provides this image of what the Great Hall at the Tower likely looked like:

This helps give me a feeling for what the rooms beyond might have been like.

How much of this is likely to end up mentioned in the novel? Likely very little, but knowing what’s what helps me imagine the scenes.

Confession: two research tricks

To estimate approximate walking distances, I find it useful to use maps.google.com.

(Too bad maps.google doesn’t have an “on horseback” option. For this, I suspect that somewhere between “walking” and “by bike” might be an approximation, given all the stops horseback travel requires to give the horses rest, food, and water, or possible exchanges.)

Another part of knowing what’s what is determining when the sun rises and sets, and (particularly in this time) when the moon is full. I can’t track that for 16th century England, so instead, to at least keep the sun and moon on realistic trajectories I’m using the current calendar for the UK using this fantastic site: timeanddate.com.

And so? So now “all” I have to do is write the #%&@ scenes.

Resources mentioned

Books Google

Elizabeth’s Women by Tracy Borman.

Elizabeth I; The Word of a Prince, by Maria Perry.

Google Maps

The Agas Map of Early Modern London

The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth by John Nichols.

The Royal Apartments at the Tower & the Scandalous Killing of Anne Boleyn, a blog post on The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Turbulent Crown: The Story of the Tudor Queens, by Roland Hui.

Timeanddate.com

Tudors — Twenty-eight Days to Wanstead by Alan Cornish. This website post is a wonderfully detailed account.

by Sandra Gulland | Jul 24, 2020 | Adventures of a Writing Life, On Research, Work in Process (WIP) |

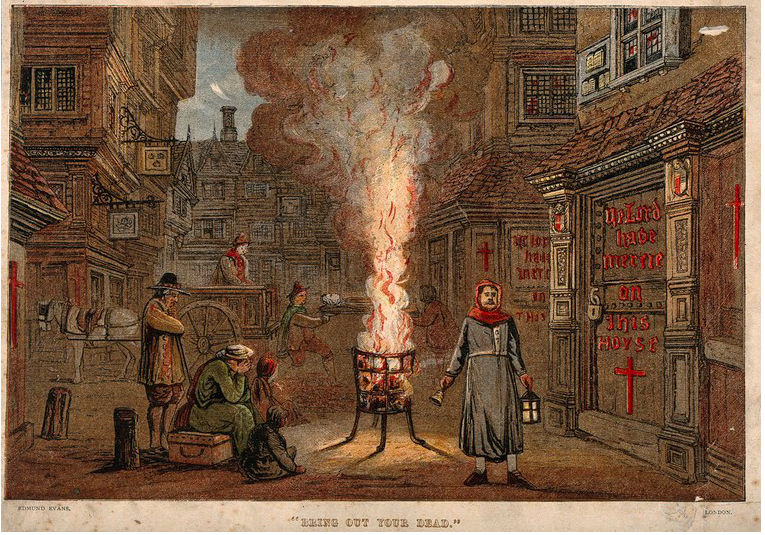

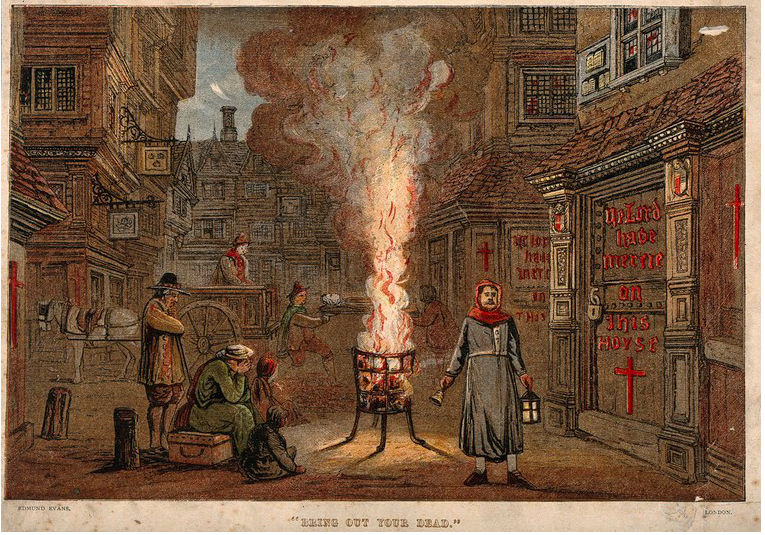

The novel I’m writing now is set in mid-16th century England. During this time period episodes of black plague and the quickly lethal “sweating sickness” came and went. With each epidemic, enormous numbers of people died.

Long ago, when I started to research, these events were simply blips on a timeline. With the advent of our Covid-19 world, such facts became far more vivid to me. I hadn’t understood the fear and heightened state of caution epidemics caused.

A 16th-century story to set the stage: a man and woman in a village in England lost children to the plague. Another child was born, and when plague returned to their town, they sealed shut the windows and doors of their home. Thanks to their precautions, their child survived: his name was William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare wrote “King Lear” (and “Macbeth,” and “Antony and Cleopatra”) during plague years when the London theatres closed down. (The rule was that once the death toll went over 30, playhouses had to close.) In short, he was out of work and had time on his hands.

“King Lear” is one of his bleakest plays, written while living in a bleak time:

The mood in the city must have been ghastly – deserted streets and closed shops, dogs running free, carers carrying three-foot staffs painted red so everyone else kept their distance, church bells tolling endlessly for funerals … (The Guardian, March 22, 2020)

Plague also changed the nature of the plays he wrote. Plague killed off men in their 30s, so the demographic of both his actors and audience changed.

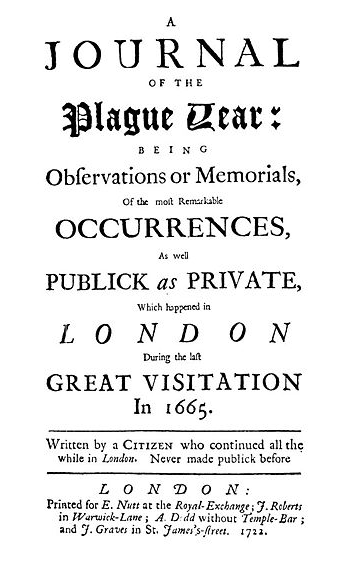

Although A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe is not, in fact, a contemporary account—Defoe was a master of what I would call fact-based fiction—it is thought to have been well-researched. I was struck, reading it, how well-organized England was in combating epidemics. For example, if infected, people were prevented from leaving their homes. One needed a certificate of health in order to travel. Interesting!

Certainly, it is reminiscent of what we are going though today:

City authorities are sane and composed concerning the spreading plague, and distribute the Orders of the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the City of London. These set up rules and guidelines for the arrangement of searchers and inspectors and guardians to monitor the houses, for the quieting down of contaminated houses, and for the closing down of occasions in which enormous gatherings of individuals would assemble.

Here’s a truly contemporary word of caution from 1665:

This poem by U.S. poet Daniel Halpern was published—astonishingly—seven years ago in Poetry Magazine. (Likewise astonishingly, he doesn’t remember writing it.)

Pandemania

There are fewer introductions

In plague years,

Hands held back, jocularity

No longer bellicose,

Even among men.

Breathing’s generally wary,

Labored, as they say, when

The end is at hand.

But this is the everyday intake

Of the imperceptible life force,

Willed now, slow —

Well, just cautious

In inhabited air.

As for ongoing dialogue,

No longer an exuberant plosive

To make a point,

But a new squirrelling of air space,

A new sense of boundary.

Genghis Khan said the hand

Is the first thing one man gives

To another. Not in this war.

A gesture of limited distance

Now suffices, a nod,

A minor smile or a hand

Slightly raised,

Not in search of its counterpart,

Just a warning within

The acknowledgement to stand back.

Each beautiful stranger a barbarian

Breathing on the other side of the gate.

Stay safe! Stay healthy!

Links of interest:

Shakespeare in lockdown: did he write King Lear in plague quarantine?

Shakespeare wrote King Lear in quarantine. What are you doig with your time?

5 People Who Were Amazingly Productive in Quarantine

What Shakespeare Teaches Us About Living With Pandemics

by Sandra Gulland | Aug 30, 2019 | Adventures of a Writing Life, On Research, The Writing Process, Work in Process (WIP) |

One of the most challenging things for me in writing a YA novel based on the scant (and most likely apocryphal) stories “Mary of Canterbury” has been figuring out where to place her. I needed to find an old village in the countryside close to Canterbury and not far from the cliffs of Dover. Proximity to the Pilgrim’s Way of Chaucer fame would be a plus. Also, because of how my story was evolving, I needed proximity to a pond.

I had originally thought that I would “simply” fabricate such a village, but I discovered that that was far from simple—at least for me. It appears that I need a real place to dig into. Ironically, without facts, I am creatively lost.

In researching the turbulent years leading up to the accession of Queen Elizabeth I, I learned of a tiny village not far from Canterbury that was rife with conflict. Like a story-seeking missile, I had found my village.

Adisham (pronounced—I think—AD SHAM), is an old village not far from Canterbury, not far from Dover, and not far from one of the Canterbury Pilgrims’ paths. And it had had, in former times, a “dangerous pond.” How good was that?

The more I learned about Adisham, the more fascinating it became. A poltergeist in a house near the church? A witch dunked in the pond? A main street called “The Street”?

The biggest bonus was the discovery of John Bland, Protestant rector of the church of Adisham.

A “Canterbury Martyr,” John Bland was one of the first to be burned alive at the stake under the rule of Elisabeth I’s half-sister, “Bloody” Queen Mary. It is also claimed, likely falsely, that he was 103 years old when executed!

I’m about to embark on a research trip to the UK and will be visiting Adisham, talking with people who live there. I’ve already learned that they warn new rectors of what happens to those who run afoul of the churchwarden and the people of the village. :-)

Here are two links on Adisham:

This one shows numerous photos of the church, along with historical details.

Here is a link to a description of the parish, published in 1800, opening with the charming words: “This parish lies exceedingly pleasant and healthy … “