The novel I’m writing now is set in mid-16th century England. During this time period episodes of black plague and the quickly lethal “sweating sickness” came and went. With each epidemic, enormous numbers of people died.

Long ago, when I started to research, these events were simply blips on a timeline. With the advent of our Covid-19 world, such facts became far more vivid to me. I hadn’t understood the fear and heightened state of caution epidemics caused.

A 16th-century story to set the stage: a man and woman in a village in England lost children to the plague. Another child was born, and when plague returned to their town, they sealed shut the windows and doors of their home. Thanks to their precautions, their child survived: his name was William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare wrote “King Lear” (and “Macbeth,” and “Antony and Cleopatra”) during plague years when the London theatres closed down. (The rule was that once the death toll went over 30, playhouses had to close.) In short, he was out of work and had time on his hands.

“King Lear” is one of his bleakest plays, written while living in a bleak time:

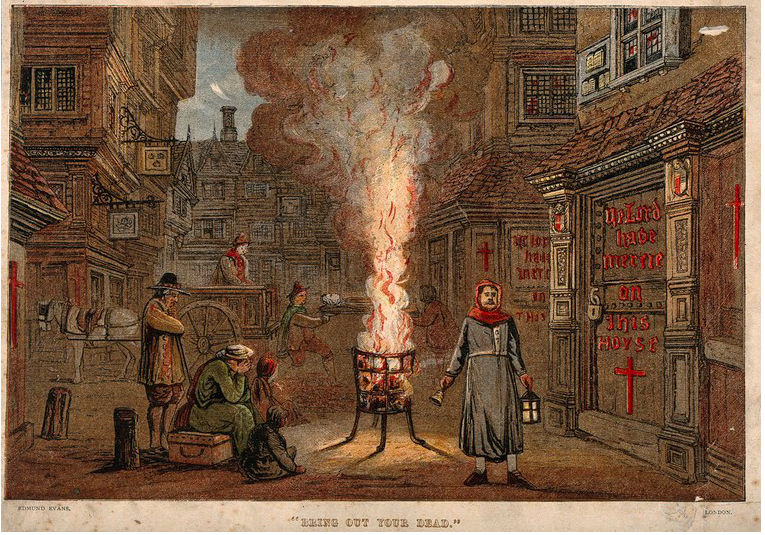

The mood in the city must have been ghastly – deserted streets and closed shops, dogs running free, carers carrying three-foot staffs painted red so everyone else kept their distance, church bells tolling endlessly for funerals … (The Guardian, March 22, 2020)

Plague also changed the nature of the plays he wrote. Plague killed off men in their 30s, so the demographic of both his actors and audience changed.

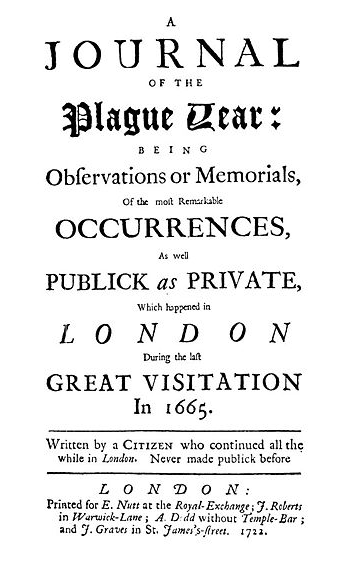

Although A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe is not, in fact, a contemporary account—Defoe was a master of what I would call fact-based fiction—it is thought to have been well-researched. I was struck, reading it, how well-organized England was in combating epidemics. For example, if infected, people were prevented from leaving their homes. One needed a certificate of health in order to travel. Interesting!

Certainly, it is reminiscent of what we are going though today:

City authorities are sane and composed concerning the spreading plague, and distribute the Orders of the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the City of London. These set up rules and guidelines for the arrangement of searchers and inspectors and guardians to monitor the houses, for the quieting down of contaminated houses, and for the closing down of occasions in which enormous gatherings of individuals would assemble.

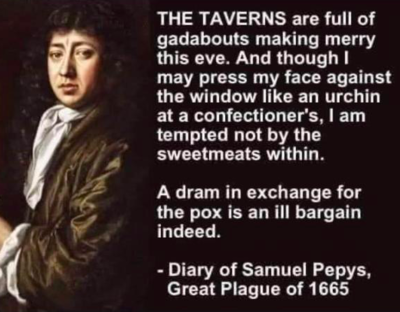

Here’s a truly contemporary word of caution from 1665:

This poem by U.S. poet Daniel Halpern was published—astonishingly—seven years ago in Poetry Magazine. (Likewise astonishingly, he doesn’t remember writing it.)

Pandemania

There are fewer introductions

In plague years,

Hands held back, jocularity

No longer bellicose,

Even among men.

Breathing’s generally wary,

Labored, as they say, when

The end is at hand.

But this is the everyday intake

Of the imperceptible life force,

Willed now, slow —

Well, just cautious

In inhabited air.

As for ongoing dialogue,

No longer an exuberant plosive

To make a point,

But a new squirrelling of air space,

A new sense of boundary.

Genghis Khan said the hand

Is the first thing one man gives

To another. Not in this war.

A gesture of limited distance

Now suffices, a nod,

A minor smile or a hand

Slightly raised,

Not in search of its counterpart,

Just a warning within

The acknowledgement to stand back.

Each beautiful stranger a barbarian

Breathing on the other side of the gate.

Stay safe! Stay healthy!

Links of interest:

Shakespeare in lockdown: did he write King Lear in plague quarantine?

Shakespeare wrote King Lear in quarantine. What are you doig with your time?