by Sandra Gulland | Jul 24, 2020 | Adventures of a Writing Life, On Research, Work in Process (WIP) |

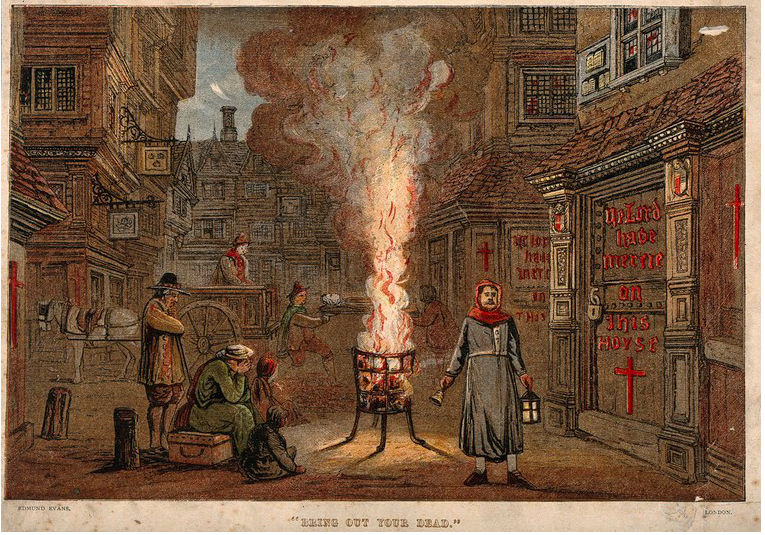

The novel I’m writing now is set in mid-16th century England. During this time period episodes of black plague and the quickly lethal “sweating sickness” came and went. With each epidemic, enormous numbers of people died.

Long ago, when I started to research, these events were simply blips on a timeline. With the advent of our Covid-19 world, such facts became far more vivid to me. I hadn’t understood the fear and heightened state of caution epidemics caused.

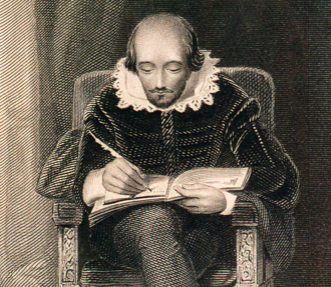

A 16th-century story to set the stage: a man and woman in a village in England lost children to the plague. Another child was born, and when plague returned to their town, they sealed shut the windows and doors of their home. Thanks to their precautions, their child survived: his name was William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare wrote “King Lear” (and “Macbeth,” and “Antony and Cleopatra”) during plague years when the London theatres closed down. (The rule was that once the death toll went over 30, playhouses had to close.) In short, he was out of work and had time on his hands.

“King Lear” is one of his bleakest plays, written while living in a bleak time:

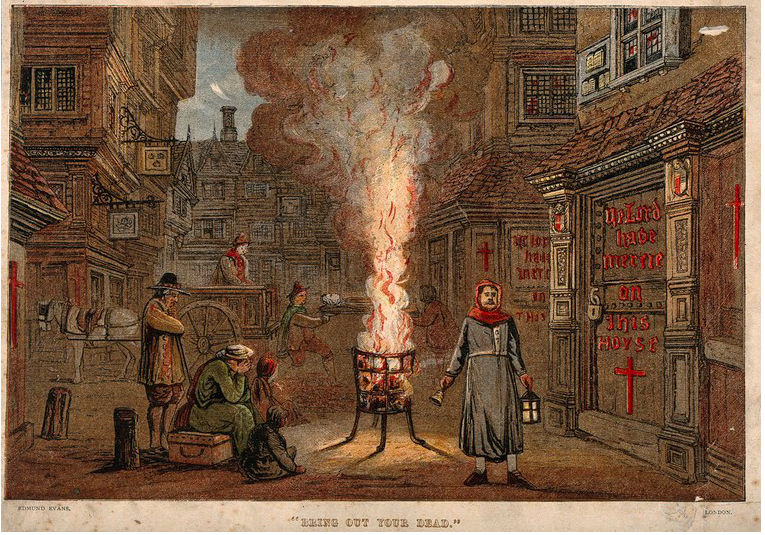

The mood in the city must have been ghastly – deserted streets and closed shops, dogs running free, carers carrying three-foot staffs painted red so everyone else kept their distance, church bells tolling endlessly for funerals … (The Guardian, March 22, 2020)

Plague also changed the nature of the plays he wrote. Plague killed off men in their 30s, so the demographic of both his actors and audience changed.

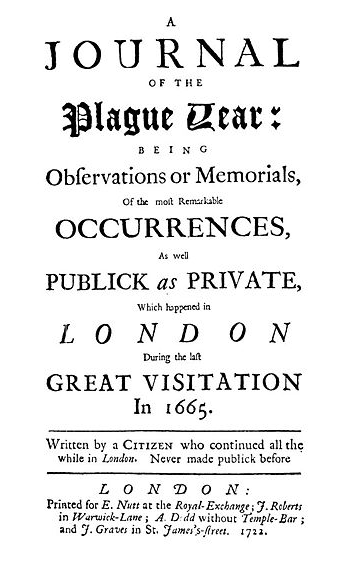

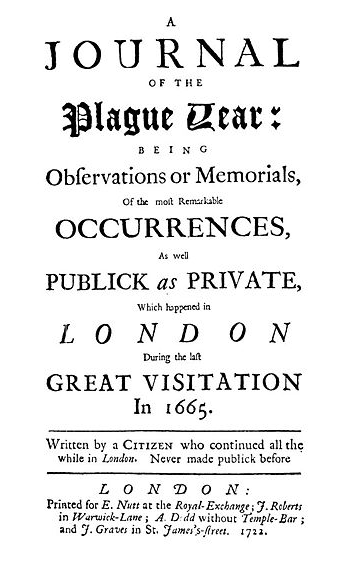

Although A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe is not, in fact, a contemporary account—Defoe was a master of what I would call fact-based fiction—it is thought to have been well-researched. I was struck, reading it, how well-organized England was in combating epidemics. For example, if infected, people were prevented from leaving their homes. One needed a certificate of health in order to travel. Interesting!

Certainly, it is reminiscent of what we are going though today:

City authorities are sane and composed concerning the spreading plague, and distribute the Orders of the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the City of London. These set up rules and guidelines for the arrangement of searchers and inspectors and guardians to monitor the houses, for the quieting down of contaminated houses, and for the closing down of occasions in which enormous gatherings of individuals would assemble.

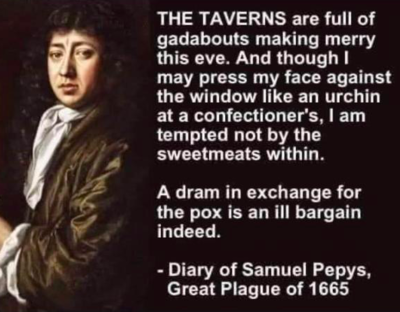

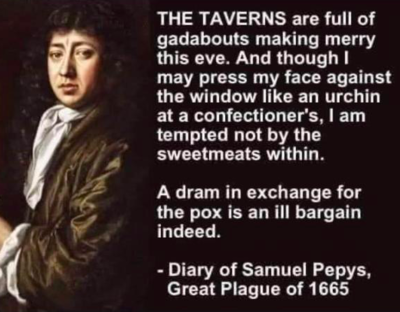

Here’s a truly contemporary word of caution from 1665:

This poem by U.S. poet Daniel Halpern was published—astonishingly—seven years ago in Poetry Magazine. (Likewise astonishingly, he doesn’t remember writing it.)

Pandemania

There are fewer introductions

In plague years,

Hands held back, jocularity

No longer bellicose,

Even among men.

Breathing’s generally wary,

Labored, as they say, when

The end is at hand.

But this is the everyday intake

Of the imperceptible life force,

Willed now, slow —

Well, just cautious

In inhabited air.

As for ongoing dialogue,

No longer an exuberant plosive

To make a point,

But a new squirrelling of air space,

A new sense of boundary.

Genghis Khan said the hand

Is the first thing one man gives

To another. Not in this war.

A gesture of limited distance

Now suffices, a nod,

A minor smile or a hand

Slightly raised,

Not in search of its counterpart,

Just a warning within

The acknowledgement to stand back.

Each beautiful stranger a barbarian

Breathing on the other side of the gate.

Stay safe! Stay healthy!

Links of interest:

Shakespeare in lockdown: did he write King Lear in plague quarantine?

Shakespeare wrote King Lear in quarantine. What are you doig with your time?

5 People Who Were Amazingly Productive in Quarantine

What Shakespeare Teaches Us About Living With Pandemics

by Sandra Gulland | May 25, 2012 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Sun Court Duet |

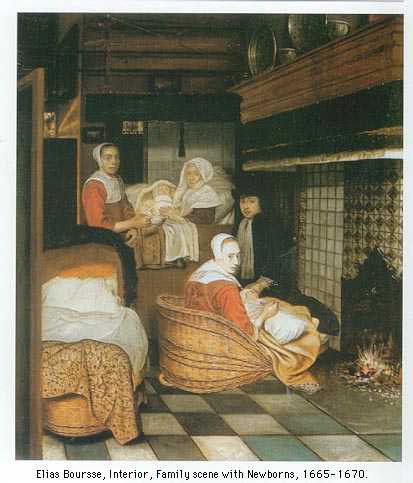

In researching 17th century maternity wear, I came upon a treasure-trove of information on 17th century daily life in Holland compiled by art historian Kees Kaldenbach. The facts of daily life were deducted in part from the detailed inventories of the Vermeer household and paintings.

Fascinating! Enjoy …

On courtship and making love

Childbirths, midwives, obstetricians

Maternity dress and trousseau

Children’s chair, potty chair

Baby child presented in a crisom

Feeding brest milk/mother’s milk

Vaginal syringe

Fire basket, fire holder

Mattress, bed, blanket. A bed was made of three layers:

- a flat mattress filled with bedstraw, horse hair or sea grass.

- a soft cover filled with feathers, down or “kapok” from silk-cotton trees. This is the layer a person would sleep on.

- sheets and blankets

Every day the sheets and blankets were folded so that the head-end and the foot-end did not touch. The pillows had to be shaken and aired for one hour, to dry the feathers, which tended to lump.

pillows (pillows, ear cushion, sit cushion, tapestry cushion — there were no chairs for the children. They were to use pillows when the adults used the chairs.); blanket,

bed cover: fascinating! The Vermeer household of 3 or 4 adults and 11 children had few blankets. People slept sitting up, two to a bedstead, propped up by pillows. The children slept in wheeled drawers which slid under the bed.

bedsheets, pillow cases, bed linen: 8 pairs of sheets were valued at 48 gilders — the equivalent of a workman’s wage for 24 to 48 days.

In the cooking kitchen

In the basement, or cellar

In the inner kitchen

Delft markets

Market bucket

Tables: fold-out table, pull-out table, round table, octagonal table, sideboard: This includes instructions on table manners. (“Do not propose to sing at the table oneself ; wait until one is invited repeatedly to do so and keep it short.”)

Trestle table

Foot stove: “One placed an earthenware container within the foot stove and filled it with glowing coals or charcoal. One then placed the feet on it. If a large dress was then lowered over it, or a chamber coat, it warmed both feet and legs.”

Tapestry table rug: “Only the most wealthy of Dutch households put Turkish rugs on the floor.”

Since I first posted this in 2012, the site moved and none of the links worked. I despaired! However, I emailed Drs Kees Kaldenbach and he kindly provided me with the new sites. Relief! This is one of the most illuminating accounts of daily life in the 17th century. For a historical novelist, it’s a gold-mine.

by Sandra Gulland | Apr 26, 2012 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Sun Court Duet |

In researching pregnancy in the 17th century, I came upon a treasure-trove of information on 17th century daily life in Holland compiled by art historian Kees Kaldenbach.

The facts of daily life are deducted in part from the detailed inventories of the Vermeer household and paintings.

I intend to go into more detail later, but one historical tidbit I found fascinating.

If a baby does not suck strongly, a mother’s milk can begin dry up. That’s as true today as it was 1000 years ago.

We remedy this problem today with the use of breast pumps. In the 17th century, however (at least in Holland), one could hire certain elderly ladies to suck. It’s not known if the milk was then given mouth-to-mouth to the baby or put into a pewter feeding bottle.

For my recent blog posts on this theme:

Where are all the pregnant women?

Before “Babies ‘n Bellies,” what did pregnant women wear?

by Sandra Gulland | Apr 11, 2012 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Sun Court Duet |

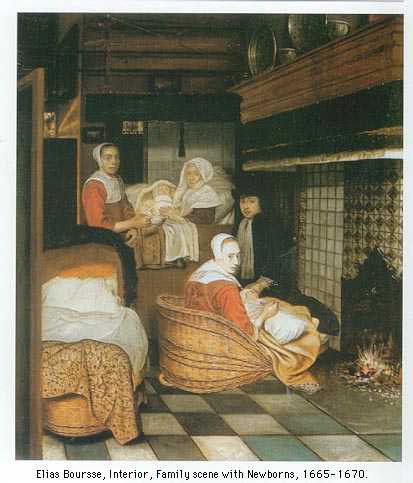

When studying history, one thing is clear: women were often pregnant. So why is it so rare to see pregnant women in paintings?

From a blog on Vermeer:

“There seem to be no depictions of pregnant women in the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century. Pregnancy was obviously considered as indecorous and not attractive and was thus kept out of public eye as much as possible.”

Perhaps that was true throughout Europe. Here are a few I found:

One painting, presumed to be of a pregnant woman, is Woman in Blue Reading a Letter by Vermeer.

Another, sometimes suspected, The Mama Lisa:

Yep, I think that’s her secret. What do you think?