The pros & cons and ups & downs of OCR and Scrivener

(Warning: tech talk ahead!)

I’ve been putting research documents into Scrivener, assuming that they were searchable. After all, one oft-stated advantage of using Scrivener is that you have all your documents in one place.

It’s true that I can put everything and anything into Scrivener, but I also need to be able to search within those documents. I mistakenly assumed that one of Scrivener’s many superpowers was the ability to make all documents searchable. In other words, I assumed that Scrivener utilized OCR (Optical Character Recognition). Not so. :-(

Having searchable documents is important for my current WIP because it’s set in the 16th century, and a number of the resources are rare and/or ancient and only available on BooksGoogle or InternetArchive. I’ve taken to clipping relevant parts of such documents (shift-control-4 on a Mac) or exporting them whole as PDFs before sending them to Scrivener. The clips are a type of image, so they need OCR to be searched, and most PDFs are not searchable as well.

And so I began to look at ways to make documents searchable before putting them in Scrivener. In the process, I discovered that anything to do with OCR opened a bottomless pit. I will try to keep this simple.

Dedicated OCR software

One possibility would be to invest in a software programme dedicated to making documents OCR searchable. The highest-rated programme for Mac is ABBYY FineReader Pro, available on trial for 30 days. I tested it out on a clip (below), and in seconds had a searchable Word document that beautifully preserved the formatting of the original.

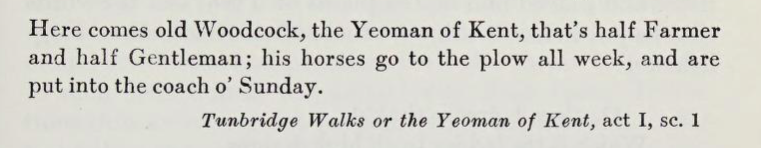

This is the original clip:

And this is the searchable Word document:

Wow.

Databases that make documents searchable

The other possibility would be to use a database that automatically makes documents OCR searchable. The advantage of using such a database is that it is—duh—a database, a logical place to store research documents. … which brings me to OneNote and EverNote.

Both EverNote and OneNote convert documents to OCR, so I decided to test them both using the test clip above.

It took well over an hour for OneNote to convert it to a searchable text, but EverNote has yet to do so even a day later!

Once made searchable, there is a way to create a copy in EverNote, a copy that can then be put in Scrivener, but it’s weird and basically unreadable, showing every word as a separate object.

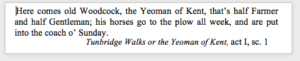

In OneNote, once the document has gone through the OCR treatment, it’s possible to easily create a searchable text version. (Control-click the document and select “Copy text from picture.”)

This is what I got from my test clip:

Here comes old Woodcock, the Yeoman of Kent, that’s half Farmer and half Gentleman; his horses go to the plow all week, and are put into the coach o’ Sunday.

Tunbridge Walks or the Yeoman of Kent, act I, sc. 1

Not as pretty as ABBYY FineReader, but not at all bad. (I did clean it up a bit.) This text can now be copied and pasted into Scrivener or wherever I want it.

Note: It would have been nice to be able to send this searchable text directly to Scrivener. I passed on this recommendation to OneNote and discovered 1) that their help menu actually helps (EverNote Help is extremely basic), and 2) that they ask how to improve. What a concept! (But do they listen? That remains to be seen.)

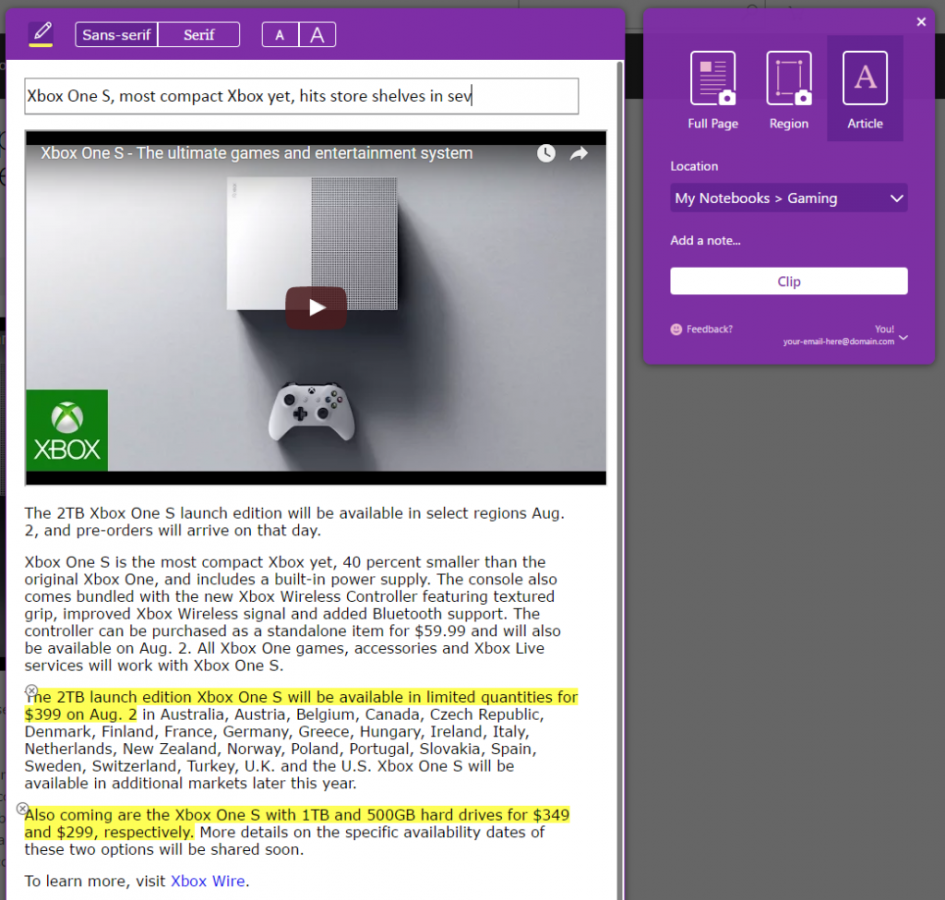

A word about Web Clippers

One beautiful thing about EverNote is its Web Clipper. With it, I can send the contents of any webpage to EverNote and, at the same time, indicate which notebook it should be filed in and how it should be tagged.

OneNote’s Web Clipper is not functional on Safari right now due to recent OS changes at Apple. I trust that this will be solved. In any case, it is available on Chrome or FireFox.

It’s a good clipper, but it’s not as useful as EverNote’s. Although you can choose what OneNote notebook to file it in, you can’t specify beyond that with tags, and you can’t file it in more than one place.

Which brings me to Tags

Being able to add tags to a document in EverNote is great. For example, I’d be able to tag an 18th-century French recipe for roasted swans as 18th century, France, food, recipes and swans. This would allow me to narrow a search for a perfect detail regarding a roasted swan snack.

OneNote doesn’t have a tag function, alas—at least not that I can see.

What about cost?

I use EverNote heavily, so I need their Premium plan, which costs $5.83 US a month when paying annually. For that I get 10GB uploads per month, and am able to search PDFs. (For more information about Evernote pricing, click here.)

OneNote is included in an Office 365 subscription package. (Some claim it’s also now available as a free stand-alone, but I’ve not been able to confirm that.) Since I’m already subscribed to the Office 365 world, I can start using OneNote at no additional cost. With OneNote, I get unlimited uploads, so win-win.

Say what? A scanner app?

Scanning pages from books is too slow to be practical. I’m delighted with the Microsoft app Office Lens, which will send a image directly to OneNote. This will save me lots of time.

For example, I took the image below with Office Lens and sent it to OneNote at 10:30 am. In under 30 minutes, it was searchable and even the all-text extract was surprisingly good.

EverNote or OneNote or … ? My conclusion

I do need a database, but given the pros and cons of OneNote and Evernote, where do I stand?

Because of the expense and inconsistent, slow and inadequate OCR function of EverNote, I have decided to migrate my extensive EverNote database to OneNote.

I should mention, as well, that there are indications that EverNote might be heading into hard times, and I don’t want to be left in the lurch.

It’s possible to import EverNote documents into OneNote using their OneNote Importer app, but judging from this note—

The importer software described on this page is still available for you to download and use, but we’re no longer actively developing or supporting this tool.

—that may not always be possible, so migrating now is perhaps wise.

I’ve never been a Microsoft fan—Mac users aren’t their priority—but OneNote for Mac looks worthy, so I’m going to make the move. I’ve also purchased ABBYY FineReader Pro, and given that I will be unsubscribing from EverNote, I’ll be coming out ahead in more ways than one. :-)

The links below might be of interest.

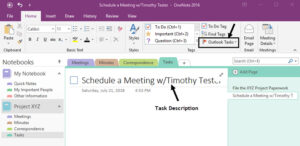

Be aware that there are differences between OneNote for Mac and the mothership OneNote for PC users. Also, OneNote for Mac has been recently “updated”—but the changes have caused quite an uproar because it’s no longer possible to arrange tabs along the top, as in this example:

I would love to have such tabs back and I’m hoping the OneNote engineers succumb. Some long-time users are even advocating reverting to the 2016 version and vowing never again to upgrade.

Evernote vs OneNote: The Best Note-taking App in 2019

Top 10 things you didn’t know about OneNote

Using Onenote for your Novel I was excited about trying out this template but it’s for an old version of OneNote, and possibly not applicable to Mac.

Why OneNote is One-Derful for Writers. Inspiring!