by Sandra Gulland | Feb 23, 2018 | Baroque Explorations |

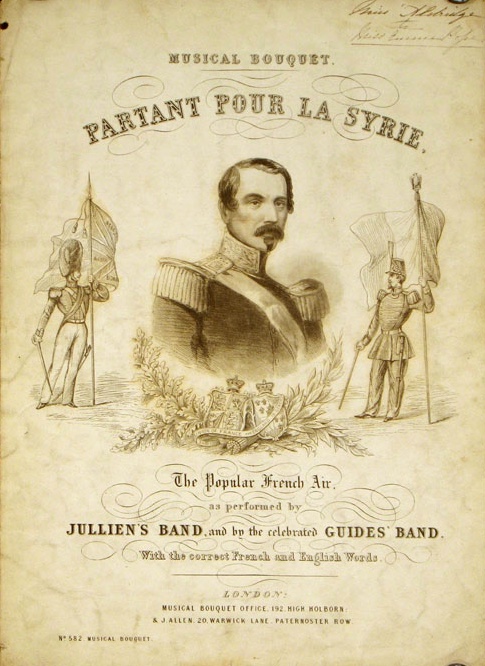

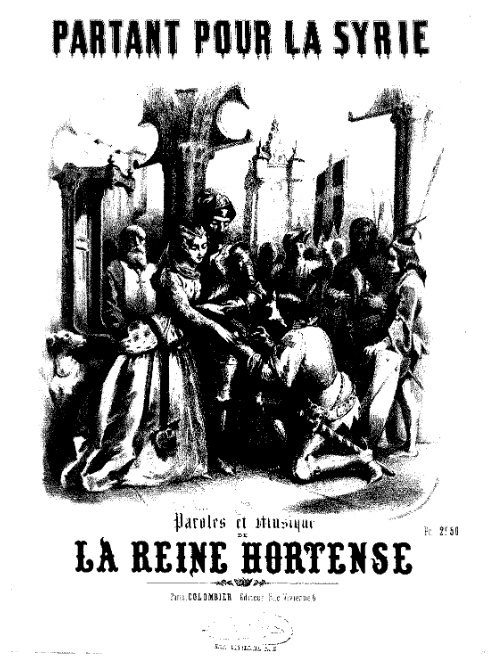

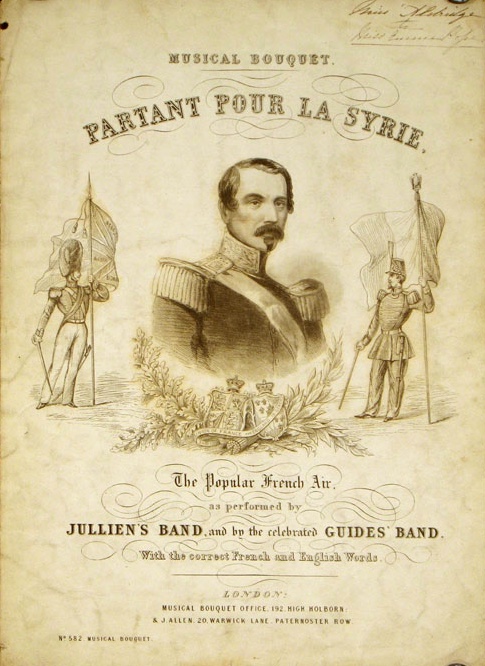

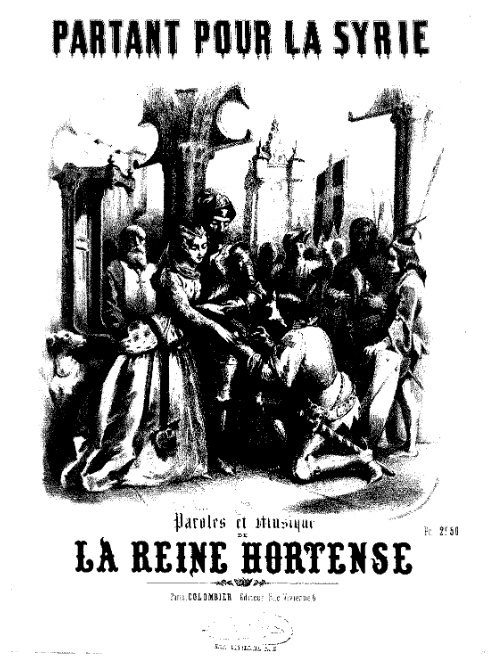

Hortense was an exceptionally creative person. At Madame Campan’s Institute she was fortunate to have Isabey for an art instructor and Jadin for music. Hortense painted and composed songs throughout her life, but she is most known for the song “Partant pour la Syrie,” which remains popular today. You can hear a lovely performance of this song here, by a singer wearing a gown very much like one Hortense might have worn.

Hortense’s creative process

How did this song come to be written? What was Hortense’s creative process? There are hints in something she wrote:

At Constance, I had few books and no collection of poems in which I could find words. I once made some verses for my brother; I tried to compose, but the obligation to find a rhyme, to confine myself to a measure, soon tired me and after a few bad verses, I was left to the music. (See the French original below.)

This gives us an idea about Hortense’s creative process: she would write melody, and search in books for the verse.

Partent pour la Syrie

She wrote that she wrote “Partent pour la Syrie” at Malmaison, while Josephine was playing tric-trac, an old form of backgammon. The date she composed it isn’t known. One theory is that Hortense wrote the melody, and that the words were created by Alexandre de Laborde in or about 1807.

Under the Restoration (when Napoleon was overthrown and monarchy restored), “Partent pour la Syrie” became the rallying song for those in support of Napoleon. Hortense’s son Napoleon III made it a national hymn.

Hortense as composer

As an adult, Hortense composed many songs, then called “Romances.”

You can “leaf” through this lovely book online: here.

A Constance, je n’avais que peu de livres et aucun recueil de poésies où je pusse trouver des paroles. J’avais fait autrefois quelques couplets pour mon frère; j’essayai d’en composer, mais l’obligation de trouver une rime, de me renfermer dans une mesure me fatigua bientôt et, après quelques mauvais vers, j’en restai à la musique.

—from “La reine Hortense et la musique” by Marie-Claude Chaudonneret in La Reine Hortense, Une femme artiste, a publication made for the 1993 exposition at Malmaison, France.

by Sandra Gulland | Jan 30, 2018 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

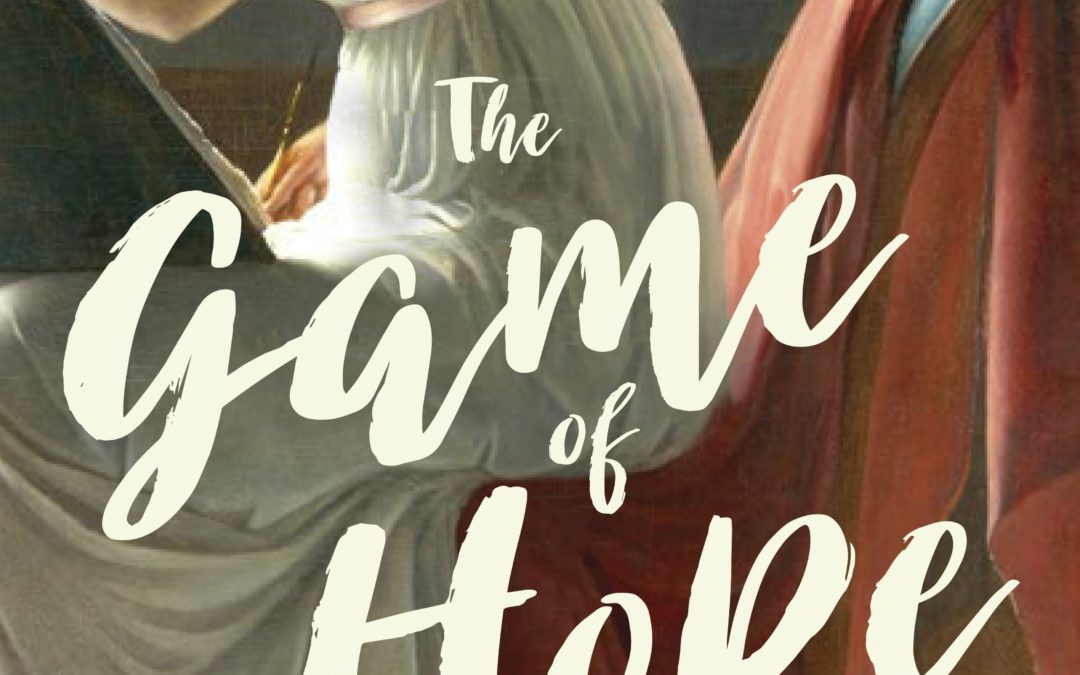

I was thrilled to read this lovely review of The Game of Hope on Net Galley. Here are some quotes:

Sandra Gulland demonstrates a masterful grasp that she has on history in her book The Game of Hope. While some authors struggle to convince their audience that they are educated in history and to fully immerse their readers in their story, Gulland has no problem displaying her understanding of post-revolution France and therefore invites her readers into a well-developed universe of Hortense de Beauharnais.

This book is well written for younger audiences of teenage girls, connecting them to the past with common issues that all preteen girls face in a timeless fashion. Gulland does not pump Hortense’s 1780 mind full of 2017 ideas, which is a genuinely refreshing change to the typical YA historical novel.

… for most preteen girls, this is still a wonderful introduction to history through the eyes of someone just like them, who truly lived, breathed, thought and felt in the same ways that they do.

How to get a copy for yourself

Should you wish to read The Game of Hope, you can request a copy on Net Galley in exchange for a review:

(My apologies: earlier I had posted that a copy of the book would be free. Well, that is true, it would be free, but it’s up to the publisher to decide who will receive the free copies, and I don’t know what their criterion is. I’m sorry if I dashed your hopes. I was fairly excited about it myself.)

But if, by hook or by crook, you do get a copy of The Game of Hope, and if you love it, I would really appreciate if you would post the review on Amazon and/or Goodreads. Reviews on these sites really matter, especially before a book is actually published.

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

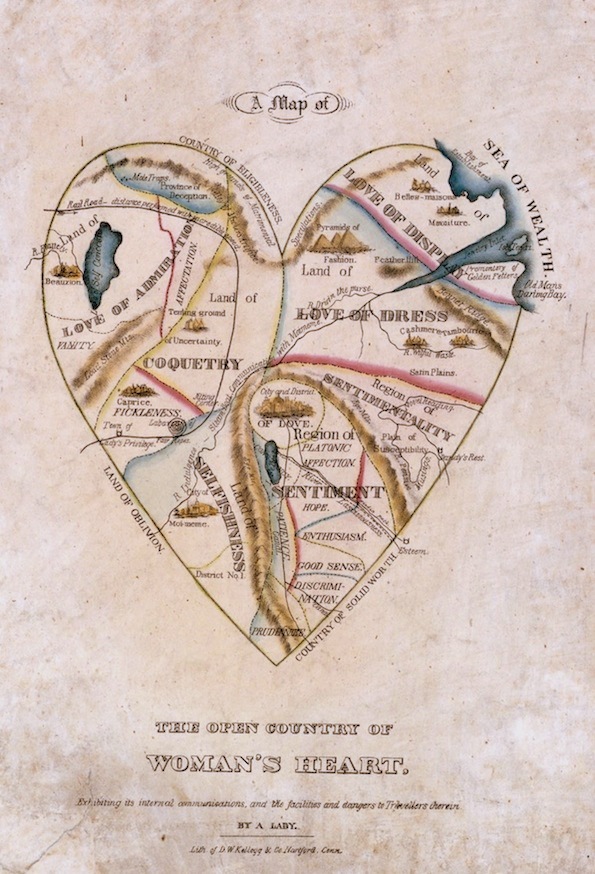

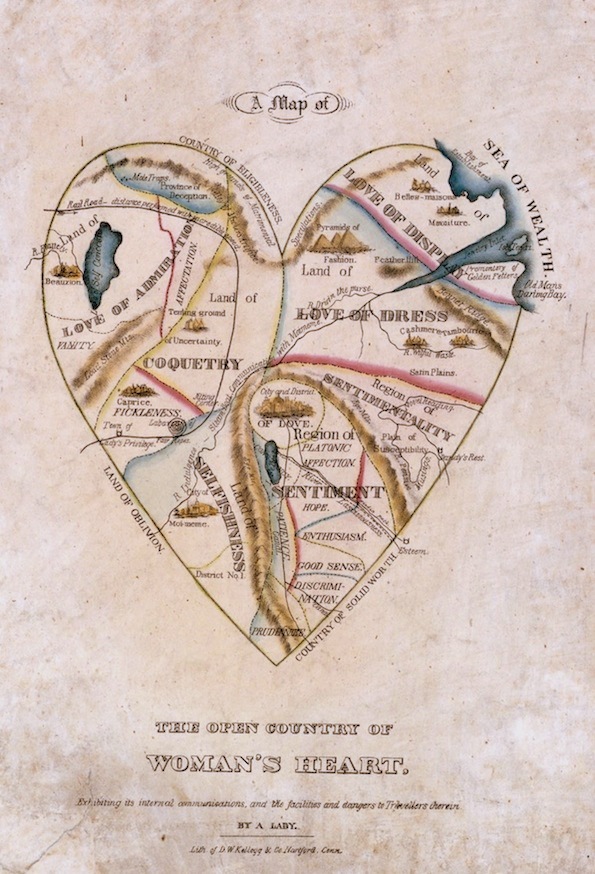

I wanted to simply put hearts at the end of this blog post in response to my request for posting reviews (it’s never easy for me to ask), but I couldn’t resist looking for something historical. This is a 19th-century map of a woman’s heart. I like that it’s described as “open country.” (I wonder what such a “map” would look like today.)

More anon … and here come those hearts!

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Jul 26, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I started writing this post six months ago, back when The Game of Hope was titled Moonsick. As part of the final revision, then, I was looking for “legal” and “illegal” words—that is, words that didn’t exist in 1800.

Here are the words and phrases I was surprised to discover were sufficiently ancient:

eavesdropping

suicide

like wild

in the pink

I continued to do this for every draft that followed, keeping a master list of okay, and not okay words.

I sent in the “final final” draft yesterday around 2:00, and last night, at dinner, I made a note to check yet another word. (Can I find that post-it now? No!)

The next step

The next time I see This Book of a Thousand Drafts (in only two weeks) it will have been transformed into “pages”—that is, looking more and more a book. At this point, there will be a limit to the type of changes I will be able to make. The odd word here and there, perhaps. A paragraph cut or added? Certainly not. Anything that would throw the layout off would topple the entire structure like a house of cards.

I recall that it used to be that an author could make minor changes at this stage—to what we then called galleys—but beyond that, he or she paid, because it was costly for the publisher to make changes.

I’m incapable of not making changes, however, and I remember going over each line carefully, dotting each page with corrections. And then the corrections to the corrections would have to be checked, etc., etc., etc. Indeed, the moment I hold the published book in my hand, I will set an extra copy on the shelf marked “changes.” This copy will also get marked up.

I was, I hope, more cautious with this final draft of The Game of Hope, and will examine the coming pages carefully—because next will be ARCs (Advance Reading Copies), and it’s painful to see glaring errors at that stage. (I trashed an entire box of Tales of Passion, Tales of Woe ARCs because of all the errors.) It’s acceptable to have a few mistakes in an ARC, but I dislike it.

And beyond …

Someone once defined publishing as bringing a forcible halt to the writing process. The publishing process can be ongoing—there will be (one hopes) a paperback edition, foreign editions—it’s never-ending. Paul Kropp once told me that he never really understood one of his novels until he rewrote it for the UK edition. The Life of Pi was first published in Canada, but I read that it underwent massive editorial surgery for its UK edition—the version the world loved.

The transition to digital has made the process somewhat smoother, but there have been glitches. I used to make editorial notes to myself in my Word document, formatting them as invisible. In the early days of the transition to digital, some of these “invisible” asides showed up in the Pages for Tales of Passion, Tales of Woe. And so, in a poignant scene, up pops my editorial: Wouldn’t her doctor have considered a venereal disease? I still remember the shock I felt seeing those words in the text of my novel. The production department lost sleep over that glitch, too, making sure that there were no others.

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Jul 4, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I’m about to send out a newsletter — my first in six months! I’ve been MIA here on this blog, as well, the result of moving into a house still under construction, all the while working to finish my next novel, THE GAME OF HOPE.

Those of you who are already signed up for my newsletters know that they include news about the Work In Progress plus a smorgasbord of book-related news of interest to my readers.

(UK author Will Self‘s writing room. How does he even read the post-its at the top?)

Each newsletter subscriber has a chance to win a free book

Plus, with each issue, I give away one of my books to a subscriber.

So: if you’re not a subscriber, sign up here. (You can always unsubscribe, of course.)

And now?

And now, the fun begins with the final edits of The Game of Hope, its cover and design. I’m soon going to be putting a wealth of background information about the novel on this website.

For now, a blog post I wrote back when this novel soon to be born was merely a gleam in my eye:

And, of course, I’ve already started giving serious thought to The Next Novel. :-)

by Sandra Gulland | Apr 26, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

{Photo by Ian Chen on Unsplash.}

I sent draft 9.8 of The Game of Hope to my editor – a partial deadline met, which is always a wonderful feeling. Right now I’m organizing my beta-reader and consultant feedback notes and making further changes.

The final-final draft is due in only two-and-a-half weeks, which isn’t much time at all given that most of that time will be given over to 1) packing up our house in Mexico, 2) flying back to Canada, 3) visiting our daughter and her wonderful family, and 4) settling back into our house in Canada.

In other words: I must keep at it.

It has been a challenging year. We sold a house and moved into a new one while it was still under construction. Needless-to-say, that was not conducive for writing. (At one point I was at my desk with headphones on, trying to ignore the six workmen in my study!)

Writing when the world seems to be self-destructing

Additionally, in truth, I have been seriously side-lined by US news: anxiety, horror, alarm, fascination … all of that. I know I’m not the only one! This gif expresses the problem perfectly:

Save

Save