by Sandra Gulland | Dec 16, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

Every stage of writing a book is a challenge—the beginning, the middle, and the end—but I think figuring out how to begin to write a book might be the most difficult.

I’m at the beginning stage of writing my next novel now. I’m going to use Scrivener for this one, and so I have a lot to learn. It’s coming.

I’ve started etching out a plot using plot “beats” I’ve gleaned from Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat.

Yet I’ve been floundering. I’m accustomed to writing biographical fiction, with reams of biographies to work from. That has its own challenges, certainly, but for me, the free fall of a novel based on someone about whom there are only a few paragraphs written—and whose existence is debated, at that—is even more challenging.

I’ve discovered a book that is excellent for the pre-plot stage: Story Genius: How to Use Brain Science to Go Beyond Outlining and Write a Riveting Novel (Before You Waste Three Years Writing 327 Pages That Go Nowhere).

I’ve resisted this book because it felt too gimmicky, but it was recommended by writers I respect and admire, and so I’m giving it a try. I’m impressed! It’s helping me to closely define my protagonist before I construct the plot. It doesn’t make it easy (nothing can), but it’s highly worthwhile. If you are at the pre-plot stage—or if you are having difficulty knowing how to begin writing—I recommend you read this book. Better yet, do the exercises.

How do you begin writing a book? What works for you?

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Jul 26, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I started writing this post six months ago, back when The Game of Hope was titled Moonsick. As part of the final revision, then, I was looking for “legal” and “illegal” words—that is, words that didn’t exist in 1800.

Here are the words and phrases I was surprised to discover were sufficiently ancient:

eavesdropping

suicide

like wild

in the pink

I continued to do this for every draft that followed, keeping a master list of okay, and not okay words.

I sent in the “final final” draft yesterday around 2:00, and last night, at dinner, I made a note to check yet another word. (Can I find that post-it now? No!)

The next step

The next time I see This Book of a Thousand Drafts (in only two weeks) it will have been transformed into “pages”—that is, looking more and more a book. At this point, there will be a limit to the type of changes I will be able to make. The odd word here and there, perhaps. A paragraph cut or added? Certainly not. Anything that would throw the layout off would topple the entire structure like a house of cards.

I recall that it used to be that an author could make minor changes at this stage—to what we then called galleys—but beyond that, he or she paid, because it was costly for the publisher to make changes.

I’m incapable of not making changes, however, and I remember going over each line carefully, dotting each page with corrections. And then the corrections to the corrections would have to be checked, etc., etc., etc. Indeed, the moment I hold the published book in my hand, I will set an extra copy on the shelf marked “changes.” This copy will also get marked up.

I was, I hope, more cautious with this final draft of The Game of Hope, and will examine the coming pages carefully—because next will be ARCs (Advance Reading Copies), and it’s painful to see glaring errors at that stage. (I trashed an entire box of Tales of Passion, Tales of Woe ARCs because of all the errors.) It’s acceptable to have a few mistakes in an ARC, but I dislike it.

And beyond …

Someone once defined publishing as bringing a forcible halt to the writing process. The publishing process can be ongoing—there will be (one hopes) a paperback edition, foreign editions—it’s never-ending. Paul Kropp once told me that he never really understood one of his novels until he rewrote it for the UK edition. The Life of Pi was first published in Canada, but I read that it underwent massive editorial surgery for its UK edition—the version the world loved.

The transition to digital has made the process somewhat smoother, but there have been glitches. I used to make editorial notes to myself in my Word document, formatting them as invisible. In the early days of the transition to digital, some of these “invisible” asides showed up in the Pages for Tales of Passion, Tales of Woe. And so, in a poignant scene, up pops my editorial: Wouldn’t her doctor have considered a venereal disease? I still remember the shock I felt seeing those words in the text of my novel. The production department lost sleep over that glitch, too, making sure that there were no others.

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Apr 26, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

{Photo by Ian Chen on Unsplash.}

I sent draft 9.8 of The Game of Hope to my editor – a partial deadline met, which is always a wonderful feeling. Right now I’m organizing my beta-reader and consultant feedback notes and making further changes.

The final-final draft is due in only two-and-a-half weeks, which isn’t much time at all given that most of that time will be given over to 1) packing up our house in Mexico, 2) flying back to Canada, 3) visiting our daughter and her wonderful family, and 4) settling back into our house in Canada.

In other words: I must keep at it.

It has been a challenging year. We sold a house and moved into a new one while it was still under construction. Needless-to-say, that was not conducive for writing. (At one point I was at my desk with headphones on, trying to ignore the six workmen in my study!)

Writing when the world seems to be self-destructing

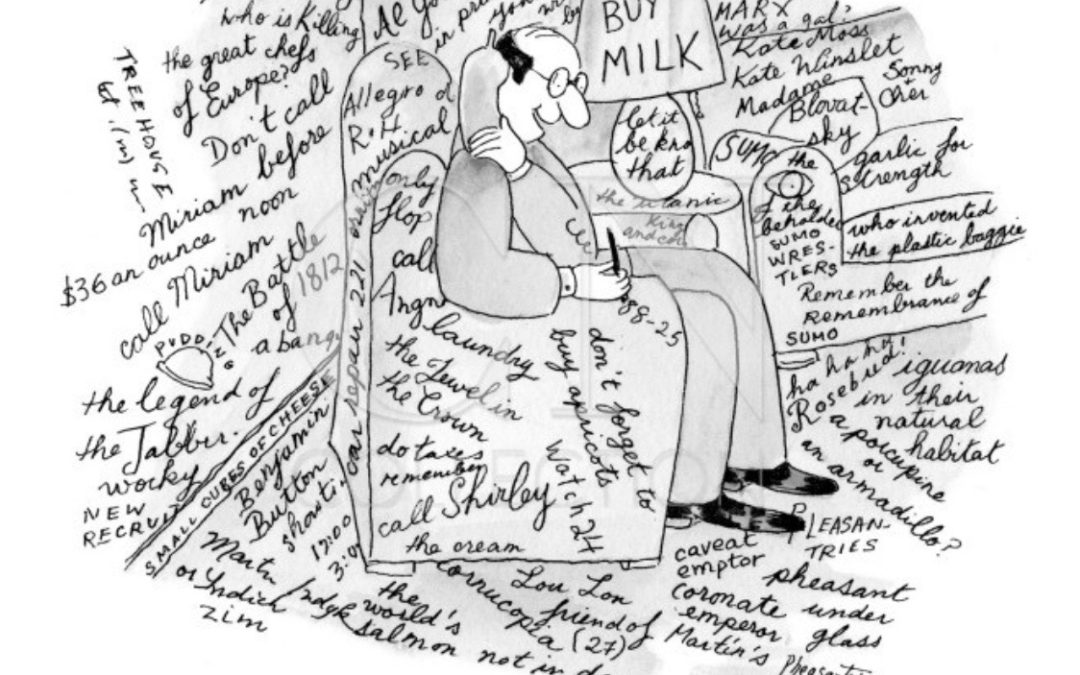

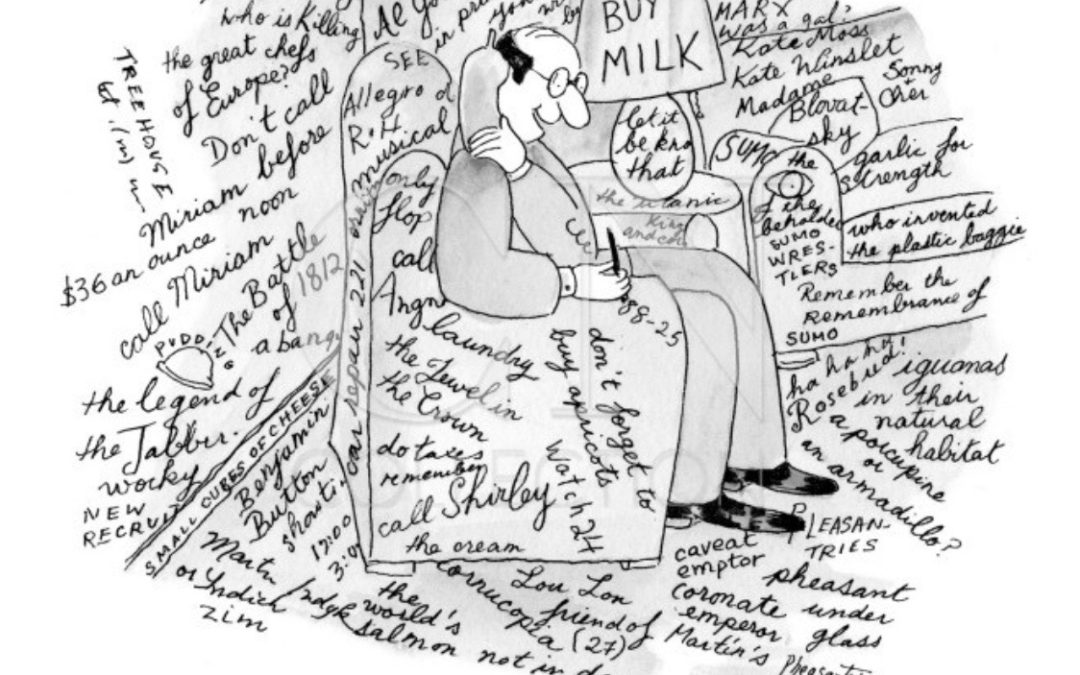

Additionally, in truth, I have been seriously side-lined by US news: anxiety, horror, alarm, fascination … all of that. I know I’m not the only one! This gif expresses the problem perfectly:

by Sandra Gulland | Jan 29, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Publication, Resources for Writers, The Writing Process |

Figuring out a novel’s “elevator pitch” — the summation of a story in a sentence or two — is invariably difficult for novelists, at least it is for me. My mind does not lend itself to reductions. I’m more of the expanding type. (Not an asset.) These 4 formulas — which I’ve gathered from hither and yon in decades of reading books on writing — are helpful in getting at the core of that unwieldy beast: a novel.

The 1-sentence formula

When _____ [OPENING CONFLICT]

happens to _____ [CHARACTER],

he/she has to _____ [OVERCOME CONFLICT]

in order to _____ [COMPLETE QUEST].

As applied to my next novel, The Game of Hope, I came up with:

Haunted by dreams of her dead father, a 15-year-old girl goes on a quest to find out if she was the cause of his death.

This is a tidy summary, but as with most one-sentence summaries, this doesn’t actually fit what actually happens in the novel.

The 3-sentence formula

_____ is about _____, who wants to _____.

The only problem is that _____.

As a result, he/she _____.

Yet, ultimately, he/she succeeds because _____.

One problem with this summary is that it gives too much away.

The 3-part book formula

1. The genre (i.e. “mystery novel”);

2. Parameters: what happens and what the reader getting into (“Seattle”, “a detective” “a dead boyfriend”);

3. Something left to the imagination (a dead body, a framed main character).

The Game of Hope is historical fiction for Young Adults. It’s about Josephine Bonaparte’s daughter Hortense, who hates her stepfather Napoleon and idolizes her dead father … until she finds out some unpleasant truths.

This is better, perhaps. It’s important to leave something unsaid, to tempt the reader.

The 5-part story formula

1. Character

2. Situation (What trouble that forces the character to act?)

3. Objective (The character’s goal.)

4. Opponent

5. Disaster (The awful thing that could happen.)

Make each of these elements specific.

Put them together to form two sentences.

Sentence 1: A statement that establishes character, situation, and objective.

Sentence 2: A statement—or question—that pinpoints the opponent and potential disaster.

Haunted by nightmares of her dead father, 15-year-old Hortense goes on a quest to find out if the father she idolizes is trying to tell her something. Was it her fault that he was executed? What she finds out is not at all what she expected, and more of this world than the next.

I think this is a better summary — but I don’t think I’ve nailed down the 5 elements yet.

And more …

I recently read Gotta Read It!: Five Simple Steps to a Fiction Pitch that Sells by Libbie Hawker (a book I recommend). She writes:

To construct a skeleton for your pitch, answer the following five questions as simply and blandly as you can: Who is your main character? What does she want? What stands in her way? What will she do, or what must she do, to achieve her goal? What is at stake if she fails?

Hawker’s book is about how to write a longer summation of your novel — one that might be used to send to a prospective agent, or be put on the jacket of your novel, on Amazon or in the publisher’s catalogue, for example. One begins with this short summary, the distillation of the novel, and then fleshes out “the skeleton” to represent the tone and subject of the novel truly.

The Game of Hope is soon to go into production, so it’s time for me to begin thinking how to frame the story, pitch it to readers. It’s never easy, but these guidelines help.

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Jan 23, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Resources for Writers, The Writing Process |

The day before the Woman’s March

Election Day. The Man Who Shall Not Be Named was sworn in as President of the most powerful nation on Earth. Some were cheering. The majority were in depression.

Above is a watercolour I finished that day, titled, simply, “January 20, 2017.” I see the American eagle as somewhat worn, world-weary, and just a little disgusted.

The morning before the Women’s March

The morning of the Woman’s March, a friend on Facebook asked why women were marching. Perhaps, she suggested,

”… they would be better served by watching what ensues and then, if dissatisfied, work on finding a candidate who can better represent their goals.”

Here was part of my answer:

I doubt that anything will be accomplished, at least in the short-term, although it may get dialogue going and help the silent supporters know that there are others out there who feel as they do. That, in turn, may encourage them to speak out, write letters, campaign, run for office, etc.

Politicians understand that for every letter of protest there are a certain number who agree, but didn’t write. I imagine that the same calculation applies to a march. A massive turn-out should make an impression.

Seeing that there are so many coming out in visible support of women’s issues may, for one thing, encourage women to run for office, and for those in office to reconsider their agenda.

The more practical actions are preferable, I agree, but it isn’t a do this OR do that situation. Many do “all of the above.”

The March itself

The Woman’s March was a beautiful experience here in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Hundreds (500? 700?) showed up, both men and women.

Gathering for the Women’s March in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico

Before I headed out to join friends there, I’d seen the news of massive turn-outs. By the time I returned home, the astonishing numbers were coming in.

The Woman’s March in New York City.

By the end of the day, it was said by credible sources that three million protested in the US alone! Even conservative small towns had significant numbers in their Marches. The Man Who Shall Not Be Named tweeted “Why didn’t they vote?” Perhaps he simply forgot that three million more people voted for The Woman Who Will Not Be Forgotten than voted for him.

Lo siento. I sound bitter. In fact, I am still a little blissed-out having been part of the largest demonstration in history. Click this New York Times coverage to get a sense of the crowds.

The morning after the Woman’s March

So, what was accomplished? I believe that in fact the Woman’s March of 2017 may have accomplished a great deal. Politicians who care about the public will have noted the turnout, and (hopefully) will give some thought to how they might vote on women’s issues. Opposition to The Man Who Shall Not Be Named was unified, energized by the experience. Some who had never made their views public before will now become active.

I leave you with two Tweets:

And this one:

In closing, a word about writing and books :-)

Lest you fear that this blog has been hijacked by political concerns, I should note that I am reading Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeline Thien — a well-lauded novel on the Chinese Revolution by a Canadian author. (So yes — sigh — politics.)

Also, I sent the last draft of my YA novel to my editor. It’s with teen beta readers and consultants now.

And so: a rest? Not exactly! We’re moving into our new house in San Miguel de Allende a week today.

SaveSave