by Sandra Gulland | Jun 3, 2009 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

.

I’ve finished reading The 101 Habits of Highly Successful Screenwriters: I got a lot out of it. I’d love to see such a book on highly successful novelists, but in spite of the differences between novelists and screenwriters, there is a lot to be learned here.

I’ve finished reading The 101 Habits of Highly Successful Screenwriters: I got a lot out of it. I’d love to see such a book on highly successful novelists, but in spite of the differences between novelists and screenwriters, there is a lot to be learned here.

I love this quote on procrastinating:

“I know when I’m about to write when I become a neat freak and start rearranging the pens and pencils around … ” [Steven DeSouza, page 95]

There was quite a bit on outlining before writing, which supports the process I’m using now.

“I try to build the story as cleanly as I can, make sure the structure works, then I write it really badly, as fast as I can … ” [Akiva Goldsman, page 107]

This same scriptwriter also had this to say:

“Unfortunately, people believe that their first thing should be great. Writing is like anything else. You’re not supposed to write a page and expect it to be good. You have to write a thousand bad pages to get to that one good page.” [Akiva Goldsman, page 123]

I feel that with the first two (unpublished) novels I wrote I didn’t understand that one, two or even three drafts were not enough. Often, beginning writers don’t give themselves enough time.

“The reality is that in order to be good at it, it will probably take you as long as any other profession to master the craft.” [Michael Schiffer, page 125]

More tomorrow …

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 18, 2009 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I met Catherine Mayo last year in San Miguel at the San Miguel Writers’ Conference. Since then I’ve been keeping in touch with her through her blog(s), Facebook, and now … sigh … Twitter (the latest in Net addiction). As well as charming, she’s a wonderful writer and teacher.

She has a historical novel coming out soon: The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire. I am very much looking forward to reading it.

She has a historical novel coming out soon: The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire. I am very much looking forward to reading it.

But the subject of this post is the list of books she recommends for novelists. Many of my own favorites are on it:

From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction by Robert Olen Butler;

Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting

by Robert McKee;

Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel by Jane Smiley.

But there are a number I know nothing about. This one I will definitely be ordering:

The War of Art: Winning the Creative Battle

by Steven Pressfield.

Because the writing life is often a war: a battle for time, for discipline.

[Note—for the list, go to: http://tinyurl.com/cdmlmx]

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 9, 2009 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

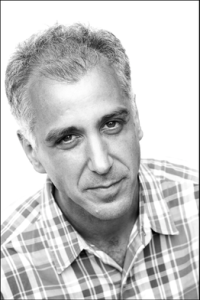

The Adam Braver discussion on Readerville.com is over (although it will no doubt remain on-line). A number of things were said about that favorite subject of mine: the line between fact and fiction.

Karen Templer:

… any historical record has gaps in it, things we don’t and can’t know. If a writer takes the liberty of filling in those gaps, then we’re looking at fiction rather than nonfiction. But there’s no bright line between fiction and nonfiction … , and historical fiction (for want of a better term for books-that-include-real-people-or-events) is a long continuum. “Girl with a Pearl Earring” has real people in it, but the story is entirely fiction. Nobody knows who the girl was; Tracy made the whole thing up. So let’s say a book like that goes at the fiction end of the continuum. Then at the other end, what would be the nonfiction end, you’ve got a book like Capote’s, where it’s extensively researched and based not very loosely at all on real people and events, but narrative devices are used in the telling of those events. So it’s closer to documentary, but it’s literary documentary.

Adam Braver, in responding to a number of posts, said:

… the nature of storytelling has always been a combination of real details and added details—sometimes consciously for the sake of narrative, and sometimes unconsciously, as our memories reconstruct the events for a better narrative. So in that vein, I don’t mind these blends.

And then he said something very dear to my heart:

On an ethical level, however, I do think one has to be upfront with a reader, as there becomes an implied contract.

I think this “contract”—often in the form of an Author’s Note —is important in fact-based fiction. The reader needs to know where he or she stands.

Braver again:

Most of the unbelievable stuff is the real stuff. My imagination works best at seeping through the cracks, not in creating the larger than life structures.

That’s often how I work.

Here’s from Karen again:

It makes no sense, I know, but when I hear “historical fiction” I think of events/people further back in history than the ’60s. But I’d also have a hard time applying it to a book like yours with a more (pardon the term) postmodern structure. Can a thing be postmodern historical fiction? I don’t know. But I think I’m sticking with “literary documentary” when trying to describe your work in particular.

And so, a new genre is born: postmodern historical fiction. I love it.

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 2, 2009 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

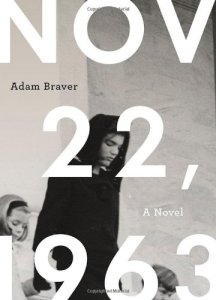

I’ve posted before about Adam Braver‘s novel, Nov 22, 1963. It’s a novel about that day, the day President Kennedy was shot, but mostly it’s a novel about Jackie Kennedy. It’s beautifully, artfully, achingly spare: a work of art in words.

I’m excited about his participation on Readerville.com this week: click here if you’re interested. I’m especially interested, because of that subject so dear to me (for obvious reasons): the intersection of fact and fiction.

To quote Braver:

One of the things that I’d been thinking about for the past couple of years is the equation: stories + memories + facts = history. This doesn’t necessarily have to apply to history as “the historical record,” but also to our family histories, personal histories, social histories, etc. From a writing standpoint, it was also about finding the somewhat artificial distinction between genres—namely fiction and nonfiction. When you deal with facts, memories, and stories, I’m not sure it’s possible that anything can be pure fiction or pure truth.

I love this:

I really wanted to write a book that consciously combined those elements: where the facts were facts, the stories were stories, and the memories were memories. Put them together in one space, yet let each one speak for itself.

And this:

I’ve always been attracted to books that allow the quiet moments to tell a bigger story, and, I suppose, I was trying to follow in that suit. It wasn’t a matter so much of sifting through so much information, and then whittling it down. It was that conscious/subconscious radar for finding the little yet moving details.

I sent the current draft of the plot off this morning for a writers’ group meet this coming Friday, so I’ll have some time to following this fascinating Braver dialogue.

by Sandra Gulland | Nov 19, 2008 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I know I’ve mentioned before how I love to listen to Barbara DeMarco-Barrett‘s Writers on Writing podcasts when I’m doing the dishes, or sitting in an airport, or driving long distances. During this last long bout of travel (the last for a bit, I pray!), I enjoyed a number, but one in particular stood out for me: an interview with NY literary agent Donald Maass. I’ve read Donald Maass‘ book Writing the Breakout Novel—and I wish I had it here with me now in my office in Mexico, because there are a number of interesting things he has to say in it.

Before writing the book, Maass made a systematic study of the novels that made the NYT bestseller list, wishing to identify what it was about a novel that made it outstandingly popular. I’m not attempting to be a Danielle Steels or Stephenie Meyer, but I do appreciate insights into what makes a story compulsively addictive. I like when a book has me deeply hooked: I love it … and that’s what I’m after.

Two things stood out in this particular interview for me:

One, that a compelling main character should be deeply conflicted right from the start: he or she must want two things that cannot co-exist.

The other thing he had to say that gave me thought was not so much about writing as about promotion: his belief that promotion and publicity isn’t what sells a book, that what sells a book is the book itself. I’d like to believe that, but I’m not convinced. I don’t think it’s an accident that the Josephine B. Trilogy sold very well in the countries that invested a great deal in promotion (and conversely).

I’ve finished reading The 101 Habits of Highly Successful Screenwriters: I got a lot out of it. I’d love to see such a book on highly successful novelists, but in spite of the differences between novelists and screenwriters, there is a lot to be learned here.

I’ve finished reading The 101 Habits of Highly Successful Screenwriters: I got a lot out of it. I’d love to see such a book on highly successful novelists, but in spite of the differences between novelists and screenwriters, there is a lot to be learned here.