by Sandra Gulland | May 17, 2019 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Mistress of the Sun, Resources for Writers, The Josephine B. Trilogy, The Writing Process, Work in Process (WIP) |

In Canada, I have a tall narrow bookcase of books—one of many I have in our house. This one includes poetry, novels I’m either reading or would like to read, and an embarrassing number of books on writing. I am a collector, apparently, a collector of books on writing.

This morning, as I was drinking my delicious mug of decaf, I took three black binders down from the top shelf. I was curious: what were they?

One was a collection of printouts of writing exercises by the New York agent Donald Maass. Another, a thick, heavy binder, was labelled Truby. In it were printouts from master story guru John Truby. I have a lot of Truby—including a series of tapes and his book The Anatomy of Story (which overwhelms me at the first chapter every time I open it). I recalled that at one time Truby offered interactive story analysis on his website; I think it was free, an amazing offering. All the printouts were from his website.

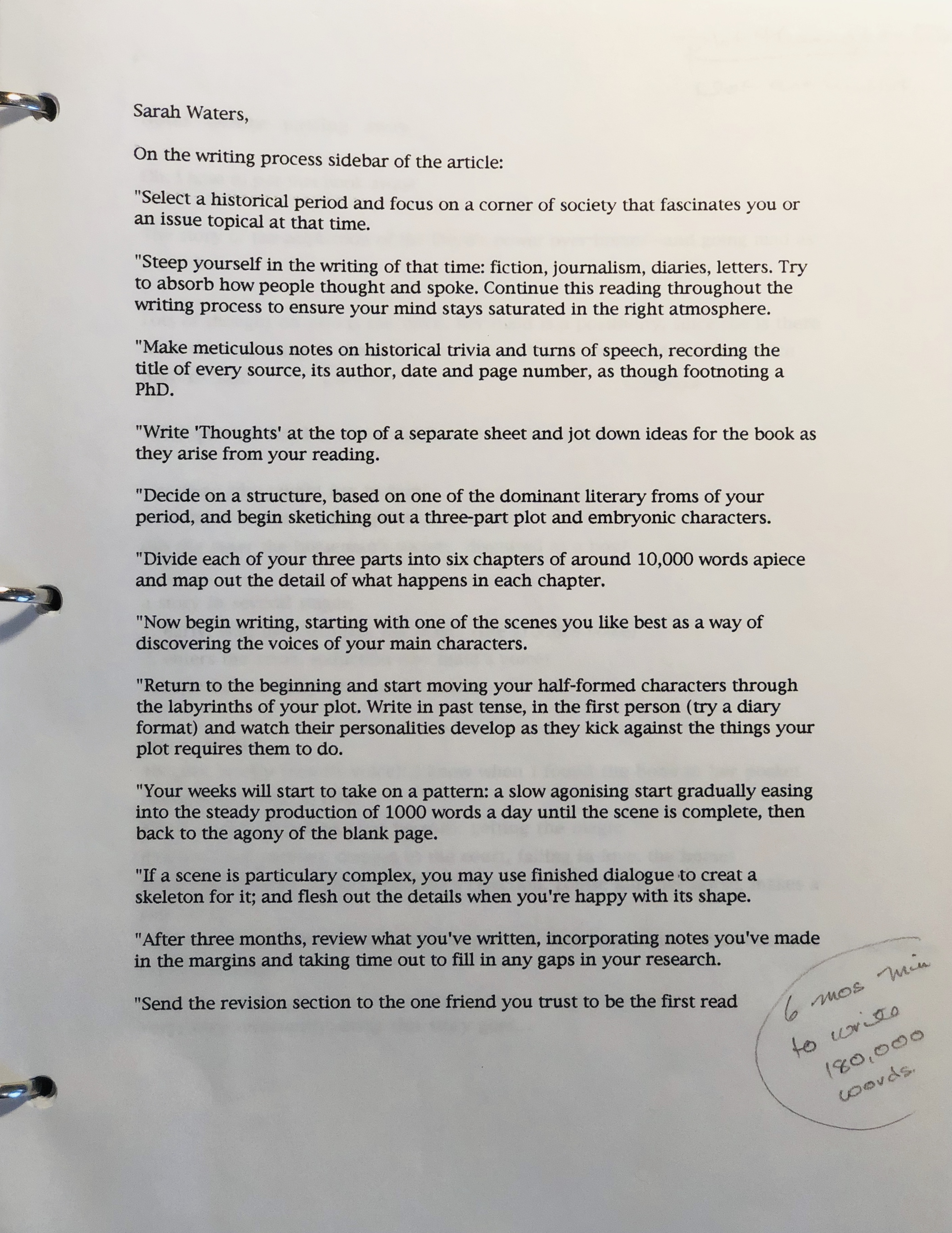

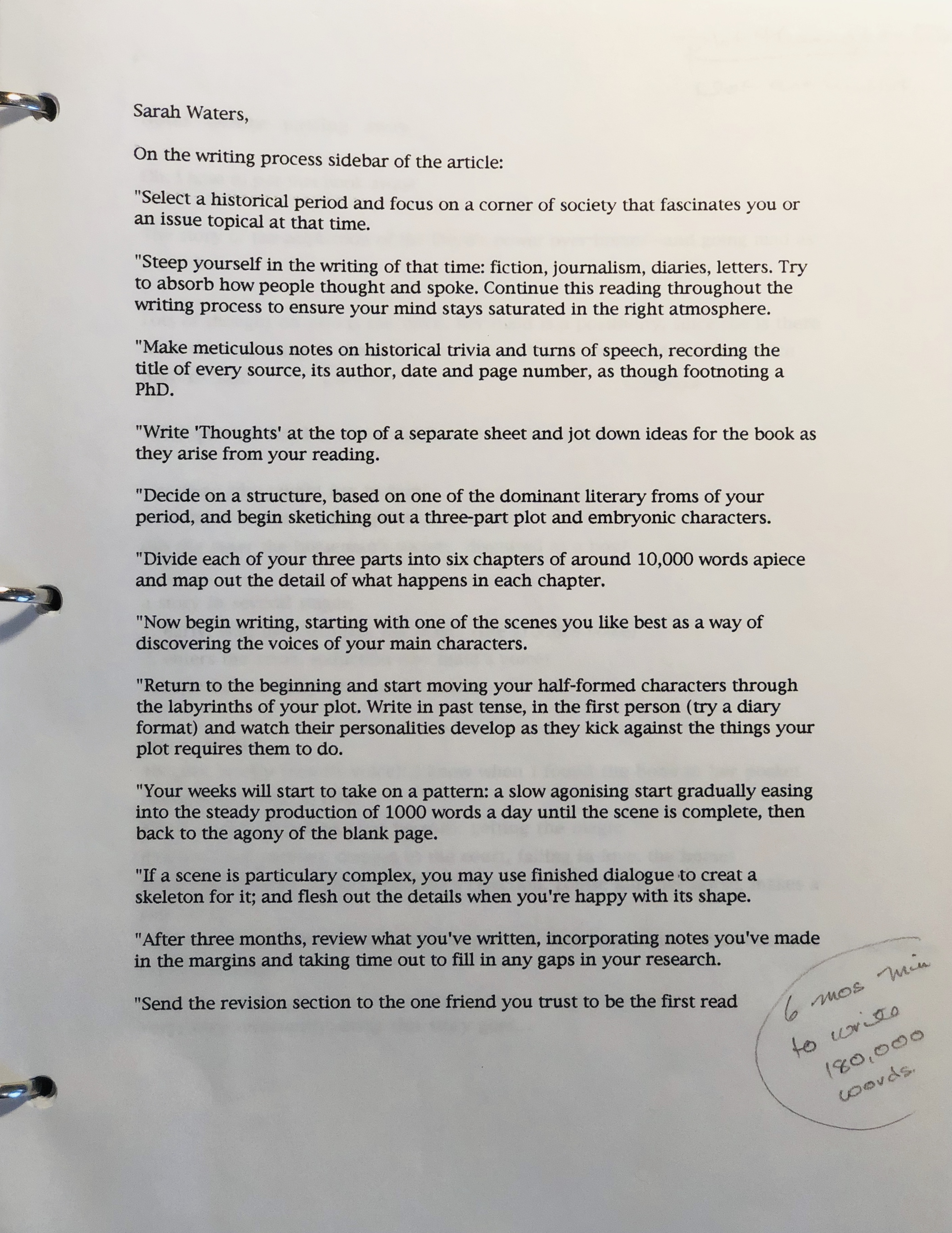

The third binder, labelled Story Tools, was of a middling size. The first page was a list of Sarah Waters’ instructions on how to write a historical novel. Her wise words are no longer online—at least not that I can find—so here it is, my gift to you. (Click here to see the full pdf.)

In the corner I had written: 6 mos min to write 180,000 words.

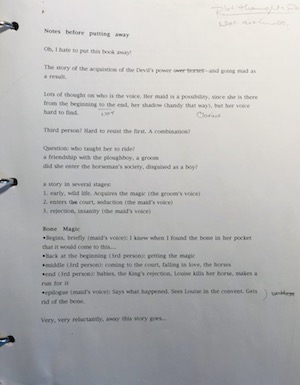

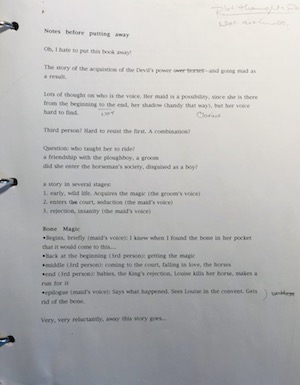

I wondered when I had written that note. The second page in the binder gave a clue.

Notes before putting away.

I must have written this after I’d been offered a contract to write the Josephine B. Trilogy. Several months before I had finally completed an acceptable draft of The Many Lives & Secret Sorrows of Josephine B., the first novel in the Trilogy. While my agent was looking for a publisher, I had started work on what was to become, nearly two decades later, Mistress of the Sun. On signing a contract for a trilogy, I reluctantly put the project away.

So: all this was Very Long Ago, as I was setting out on this 32-years-and-counting writing adventure.

Sarah Waters’ advice on how to write a historical novel is a treasure. I’ll be returning to it.

The photo at top is of Sarah Waters, 2010, by Sam Jones, as seen in the article in the Guardian on Sarah Waters’ 10 rules for writers (rules which are, of course, spot on).

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 9, 2015 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I had the honour to be asked to read a pre-publication copy of A Measure of Light by Canadian author Beth Powning. She’s already an award-winning author, and—frankly—I won’t be surprised if this novel doesn’t garner more. It certainly held me captive and in awe.

Here’s the testimonial I offered:

A Measure of Light by Beth Powning is a spellbinding work of biographical historical fiction, gorgeously written in spare, crystalline prose I found reminiscent of the finest writers of literary historical fiction today. (Geraldine Brooks, Tracy Chevalier and Hilary Mantel come to mind.) A brilliant evocation of 17th century England and America, it’s the story of one woman’s search for faith and the horrific sacrifices she makes once she finds it. Grim yet luminous—as well as illuminating. In a word: enchanting.

Believe me, I am rarely so effusive.

As I was reading the novel, I had questions about the author’s research and writing process, so I was extremely pleased when Beth accepted my invitation to answer a few questions here.

What were the unique challenges in writing about Mary Dyer?

When I first “met” Mary Dyer, I found her actions disturbing, even repellent. How could a mother leave six children for a five year period? Why would she return to them and then dedicate herself to a cause, thus once again removing herself from them? And how on earth could Mary walk into the jaws of death?

Often, what outrages me is like a shiny lure. I could not turn away from Mary’s story, and I realized that I had to find common cause with her: to put myself in her place, try to understand. I learned that it was common for 17th century parents to “farm out” their children with other families. I learned that the Puritans taught parents not to love their children “too much,” else they offend the Lord. And it occurred to me that it was very possible that Mary suffered post-partum depression. I began to understand the depth of Mary’s inner darkness and the consequent power of George Fox’s “measure of light.”

Telling her story became a kind of psychological mystery, a who-dun-it, where I knew the ending, but had to trace the steps leading up to it.

Reading A MEASURE OF LIGHT, I was in awe of the wonderful details of daily life.

Anne lifted bread on a peel from a beehive oven at the side of a hearth. The tiny girl turned a crisp-skinned goose, hanging on a string before the fire. Bloody gut-smell stung Mary’s nose—white hen feathers stippled the floor. (Page 39.)

I’d love to know specifics about your research process, specifically with respect to daily life. What did you find most useful? How did you keep track of it all?

Writing the first draft of a historical novel is a slow process. When I write, I visualize a scene in its entirety. I imagine myself, in a visceral way, to be there; I see, smell, hear. I find it hard to proceed with the writing until I have all these elements in place. Therefore, I must maintain a complex mental balance. I am thinking about the undercurrent of the scene, its meaning and contribution to the novel’s whole; I am working on character, who is there and what they are saying and feeling; I’m conscious of the pacing of both the scene itself and its placement within the text—yet I also need to know whether there’s a fire on the hearth; if the room is lit, and by what; whether there are shadows; what is cooking in what kind of a pot over the flames; if I can hear the rumble of wheels or the neighing of horses.

I had two invaluable books for the details of daily life in the colonies. “Home Life in Colonial Days,” by Alice Morse Earle, was written in 1898. Amazingly, Alice Earle could tap into the living memory of the elders of her time, who still recalled how things used to be. Another book was “Every Day Life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony,” by George Francis Dow. For England, I used a marvelous book first published in 1615, “The English Housewife,” by Gervase Markham, filled with recipes and home-making instructions.

I had a few other excellent books about 17th century England. If they could not provide what I needed about details of daily life, I would search the internet.

I have an old-fashioned filing cabinet. In its pull-out drawers, I made major sections like England, New England, London, Puritans, 17th Century General. Within each of the sections, I placed paper files labelled gloves, writing implements, tools, money, jails. I also kept a virtual file on my computer’s bookmarks page, with links to websites. I used both systems, paper and computer, all the time.

I have a large cabinet in my study. In it is a shelf earmarked for books about Puritans, another for the Quakers, one for English history, etc. These shelves gradually filled with books that I either bought on-line or in 2nd hand bookstores. Library books, too, were parked there.

Spiral-bound notebooks fill with “notes on plot,” “notes on character.” As I write, every draft gets its own notebook— “Notes Chp. 1, draft 2;” “Notes Chp. 2, draft 3.” There are notebooks for editorial conversations.

It might sound chaotic, but in fact I keep my office highly organized. I have to be able to find all this stuff, without wasting time rummaging around for it!

Do you plot? How many drafts? When do you research?

In my last two novels (The Hatbox Letters, The Sea Captain’s Wife) I dove in without knowing where the novel would go. A Measure of Light is a true story, but since only the ending and some of the middle of Mary’s life are known, I had to work backwards. I made up Mary’s early story. Even so, I didn’t know exactly how it was all going to unfold. That happens as I write. I didn’t know about Sinny, for example, until I began to write. Then I had to pause and make up Sinny’s back-story. I love not knowing what is going to happen.

I show the first draft of every novel to my extraordinary agent, Jackie Kaiser. Jackie always provides superb feedback at this point, and my second draft is quite different from the first. There is invariably a third draft, which is perhaps the most difficult, because I think that I “got” it in the second. (But no!) Jackie doesn’t show my novel to my publishers until the 3rd draft is complete. The 4th draft is the one I make based on the comments from my editor. (Craig Pyette for A Measure of Light.) I had already done a lot of work before Craig saw this manuscript, but even so he had a great deal of brilliant advice. So substantive changes were made. Together with Craig, I worked through the novel about six more times. The changes, of course, get smaller and smaller. I suppose you can call those drafts, because a slightly changed novel emerges each time; but really, after the 5th draft, the novel is basically “there.”

I start with the research. I read and read and read. I underline in books that I own, take notes from library books; it’s just as if I were back in university, taking a history course. As I study, ideas come to me about how I will transform these facts into fiction. I keep track of my thoughts in a notebook. There is always a moment when the longing to transform the information into a rich, living story becomes acute, and I simply begin to write. Too MUCH research can kill the novel. I become intimidated by the sheer volume of information that exists about the period, and strangely depressed by the historian’s objective voice.

A MEASURE OF LIGHT traverses many places, and over a considerable stretch of time: London (1634-1635), Boston (from 1635 to 1638), Aquidneck (from 1638 to 1651), England (from 1651 to 1655), New England (from 1657 to 1660).

Even so, it is a fairly spare novel, under 300 pages. How did you grapple with all the shifts in time and place?

Although I don’t plot, I did in fact block out the time periods before beginning. I begin at the beginning, and remain in each time and place until that section’s story is told, writing as much or as little of it as I think is needed. The first section, “London,” was, of course, enormous (SO much information, such a rich period!) and was heavily cut. The next, “Boston,”was the most difficult, since so many crucial things happened in that period, most of them necessary to understanding the rest of Mary’s story. The other periods grew or shrank during the editing process. A section which took place in Barbados was completely cut.

During the early drafts, when I realize that some parts of the story will take place over a long period of time without a lot happening, I simply write a few paragaphs indicating the passage of time and go on. Then I return later and fill it in. As a novel progresses, what comes later effects what came before, and vice versa. It’s like kneading dough. You fold and turn and fold again, working all the elements into one loaf, so to speak!

I always make a time chart, too. It’s a long roll of paper. Along the top are the characters, with their dates of birth. Along the left are the years. So in 1637, say, you can see at a glance what everyone in the novel is doing, how old they are, where they’re situated. I include a column down the left-hand side for historical events, so you can also remember what’s going on in the world. This is done with pencil and paper, not on the computer.

Your prose is wonderfully rich in similes.

Her heart had been smoothed like sand with the waters of other women’s assurances … (page 21)

They did not speak to one another, as if the leaf-scented air was itself a flux binding peace and could be broken by the merest whisper. (Page 76.)

She put fresh wood on the fire and sat reading her Bible in its light, looking up from the pages occasionally, as if listening for a voice she might trust. (Page 116.)

Clearly, you have a poet’s heart. I hesitate to ask about technique, yet I am curious.

I make them up myself. It’s how my brain works, so in fact I am constantly “shutting down” similes. The book could easily have far, far too many. They rise like bubbles slanting through…oops, there I go. In fact, I do work very hard to get them right. I sit with my face in my hands and search my memory bank. One of the things I say to myself is: how is it really. And then: think sideways. What does the bark of an ancient spruce tree REALLY look like? How does it feel to the tips of the fingers? Is there something I can compare it to that will bring this alive for the reader? This, again, is why writing is a balancing act. I’m dwelling on this problem, aware that it is only a beat or two in a large symphony.

“Think sideways”—I like that. Thank you so much, Beth!

I was delighted that Beth mentioned the work of Gervase Markham. When I was researching Mistress of the Sun, I became so absorbed in The Compleat Horseman—his work on horsemanship—that I began “translating” it into modern English.

Here is the publisher’s description of Beth’s wonderful novel:

Set in 1600s New England, A Measure of Light tells the story of Mary Dyer, a Puritan who flees persecution in Elizabethan England only to find the Puritan establishment in Massachusetts every bit as vicious as the one she has left behind. One of America’s first Quakers, and among the last to face the gallows for her convictions, Mary Dyer receives here in fiction the full-blooded treatment too long denied a figure of her stature: a woman caught between faith, family and the driving sense that she alone will put right a deep and cruel wrong in the world. This is gripping historical fiction about a courageous woman who chafed at the power of theocracies and the boundaries of her era, struggling against a backdrop of imminent apocalypse for women’s rights, liberty of conscience, intellectual freedom and justice.

I highly recommend it!