by Sandra Gulland | Mar 30, 2018 | Resources for Book Clubs, Resources for Readers, The Game of Hope, Young Adult Literature |

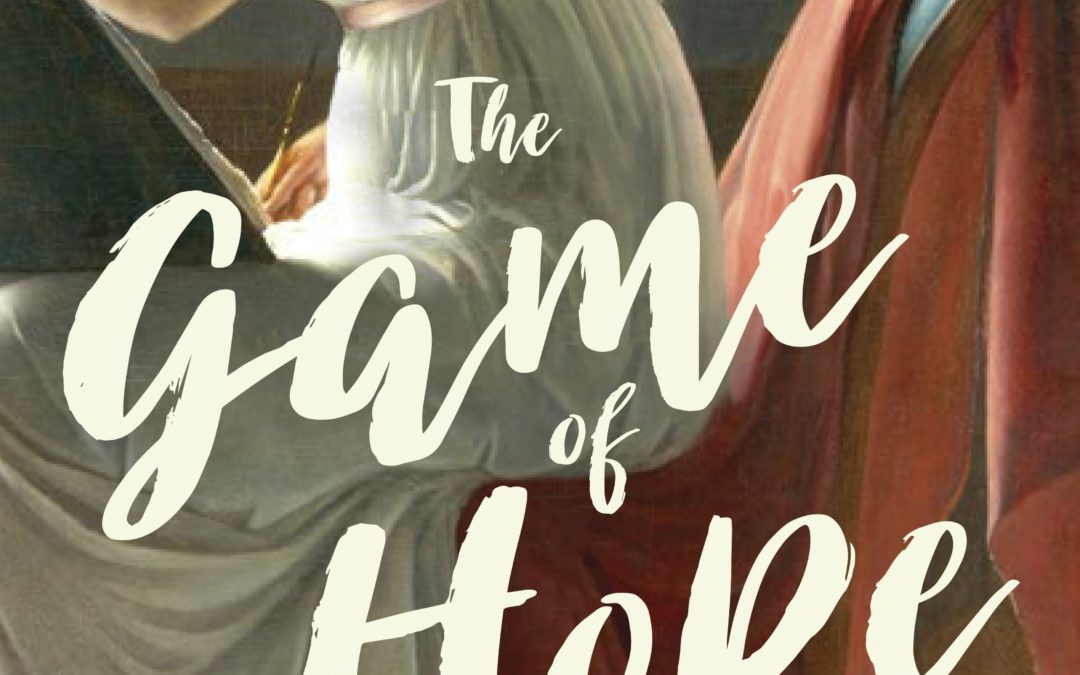

The painting on the cover of The Game of Hope is by French artist Marie-Denise Villers. It is popularly known as “Young Woman Drawing,” and can be seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The portrait is said to be of Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, but at least one art historian believes that it’s the artist’s self-portrait.

The painting was unsigned and for years it was attributed to the famous French artist Jaques Luis David. It wasn’t until 1995 that Villers was credited for the work.

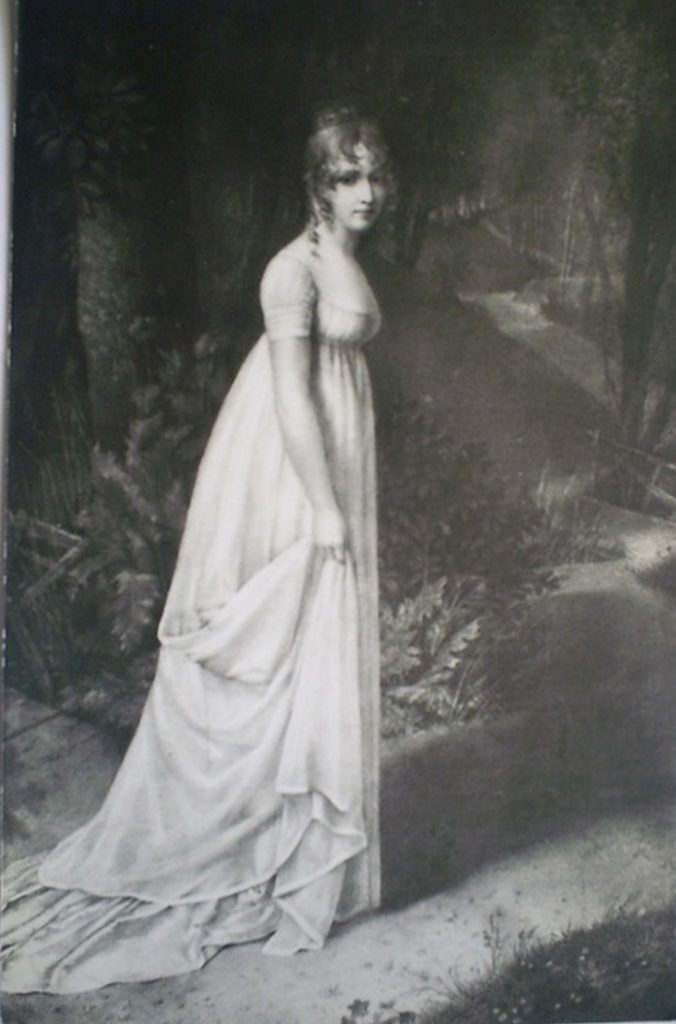

Although the painting is not a portrait of Hortense de Beauharnais, the young woman looks rather like her, I think, especially in spirit. Here is a portrait — possibly a self-portrait — of Hortense as a teen.

Hortense (possibly a self-portrait).

For portraits of Hortense at all ages, go to my Pinterest board.

For more on this intriguing painting, read “Prof. Anne Higonnet reveals a new twist in storied Metropolitan Museum of Art painting.” Higonnet’s slide presentation on this painting — “White Dress, Broken Glass” — can be seen online, although without the accompanying text it’s difficult to surmise her conclusion.

by Sandra Gulland | Feb 27, 2018 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I’ve a newsletter about to go out, and I want to remind my wonderful readers who aren’t on my newsletter mailing list that you’re missing a chance to win one of my books — or (for the first time!) win an Audible edition of the entire Josephine B. Trilogy. The choice would be yours.

Click here to sign up. (Of course, you can unsubscribe at any time.)

Wonderful early reviews for The Book of Hope

Some readers have received an Advance Readers Copy (an “ARC”) of The Book of Hope, or read a free copy on NetGalley. It’s not possible for them to post reviews on Amazon until publication day, but it is possible to post a review on GoodReads and NetGalley.

It’s exciting (and anxious-making) to see early reviews coming in. My favourite so far is this one from Chelsea M. on NetGalley:

“Loved this read! It had me hooked!”

Swoon. That’s the best review a book can get, in my opinion. Thank you, Chelsea M., whoever you are.

Beta reader love

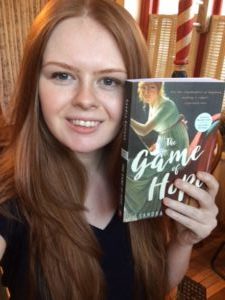

Here is a photo of one of my wonderful Beta Readers, Vanessa Van Decker, with the Canadian ARC of The Book of Hope.

Vanessa wrote that she was moved to tears to see the book. I myself was moved to tears to see the photo (above) of her smiling face with The Game of Hope in her hand.

Readers are so very special, and my team of young Beta Readers who read and commented on the early drafts of this novel were absolutely amazing.

An idea

Early readers: send me a selfie with The Game of Hope and I’ll post it to my website. A photo of the chocolate madeleines you make would be extra special. :-)

Why pre-order?

Pre-orders inform a publisher that the book is going to sell well, which publishers in turn communicate to bookstores. In short: it’s a very nice thing fans can do to help both a book and an author.

- Amazon.ca (due out May 1, in time for Mother’s Day, hint, hint :-)

- Amazon.com (due out June 26, in time for summer reading :-)

For more buying options, click here.

SaveSaveSaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Feb 23, 2018 | Baroque Explorations |

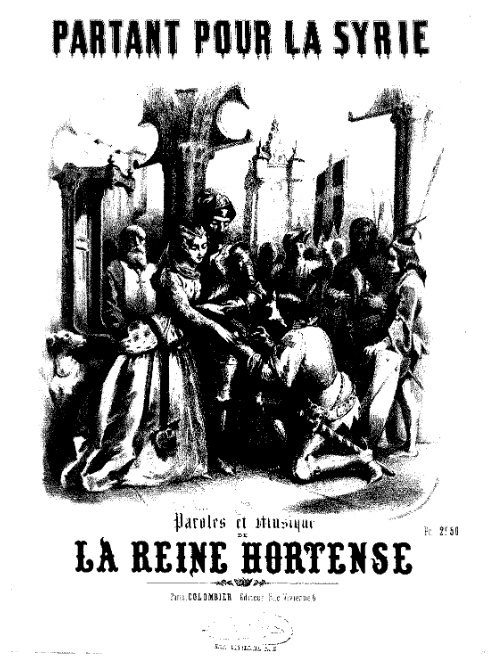

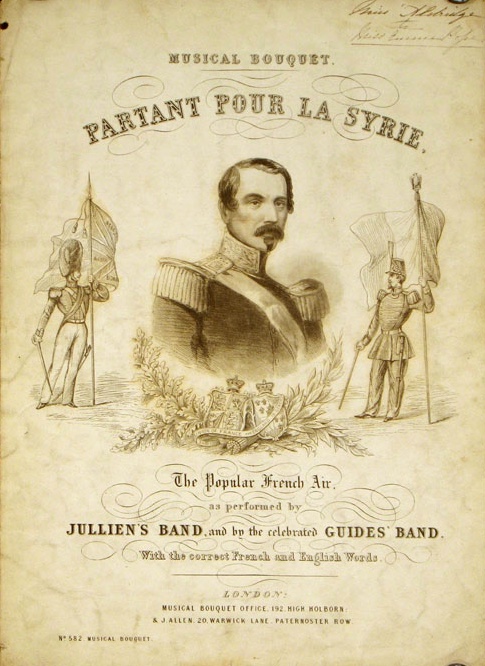

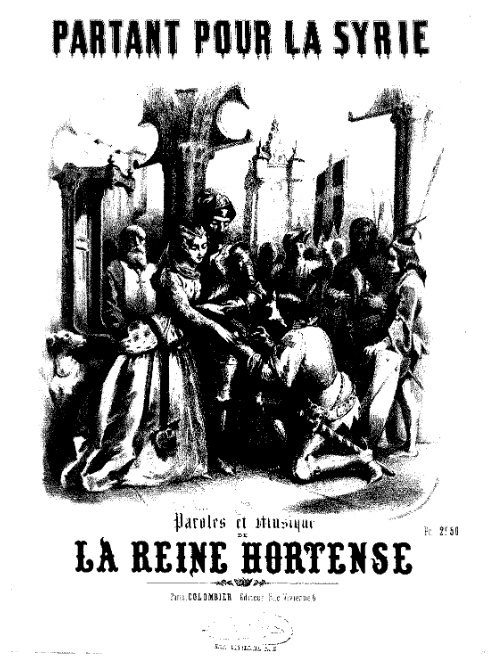

Hortense was an exceptionally creative person. At Madame Campan’s Institute she was fortunate to have Isabey for an art instructor and Jadin for music. Hortense painted and composed songs throughout her life, but she is most known for the song “Partant pour la Syrie,” which remains popular today. You can hear a lovely performance of this song here, by a singer wearing a gown very much like one Hortense might have worn.

Hortense’s creative process

How did this song come to be written? What was Hortense’s creative process? There are hints in something she wrote:

At Constance, I had few books and no collection of poems in which I could find words. I once made some verses for my brother; I tried to compose, but the obligation to find a rhyme, to confine myself to a measure, soon tired me and after a few bad verses, I was left to the music. (See the French original below.)

This gives us an idea about Hortense’s creative process: she would write melody, and search in books for the verse.

Partent pour la Syrie

She wrote that she wrote “Partent pour la Syrie” at Malmaison, while Josephine was playing tric-trac, an old form of backgammon. The date she composed it isn’t known. One theory is that Hortense wrote the melody, and that the words were created by Alexandre de Laborde in or about 1807.

Under the Restoration (when Napoleon was overthrown and monarchy restored), “Partent pour la Syrie” became the rallying song for those in support of Napoleon. Hortense’s son Napoleon III made it a national hymn.

Hortense as composer

As an adult, Hortense composed many songs, then called “Romances.”

You can “leaf” through this lovely book online: here.

A Constance, je n’avais que peu de livres et aucun recueil de poésies où je pusse trouver des paroles. J’avais fait autrefois quelques couplets pour mon frère; j’essayai d’en composer, mais l’obligation de trouver une rime, de me renfermer dans une mesure me fatigua bientôt et, après quelques mauvais vers, j’en restai à la musique.

—from “La reine Hortense et la musique” by Marie-Claude Chaudonneret in La Reine Hortense, Une femme artiste, a publication made for the 1993 exposition at Malmaison, France.

by Sandra Gulland | Apr 8, 2017 | Baroque Explorations |

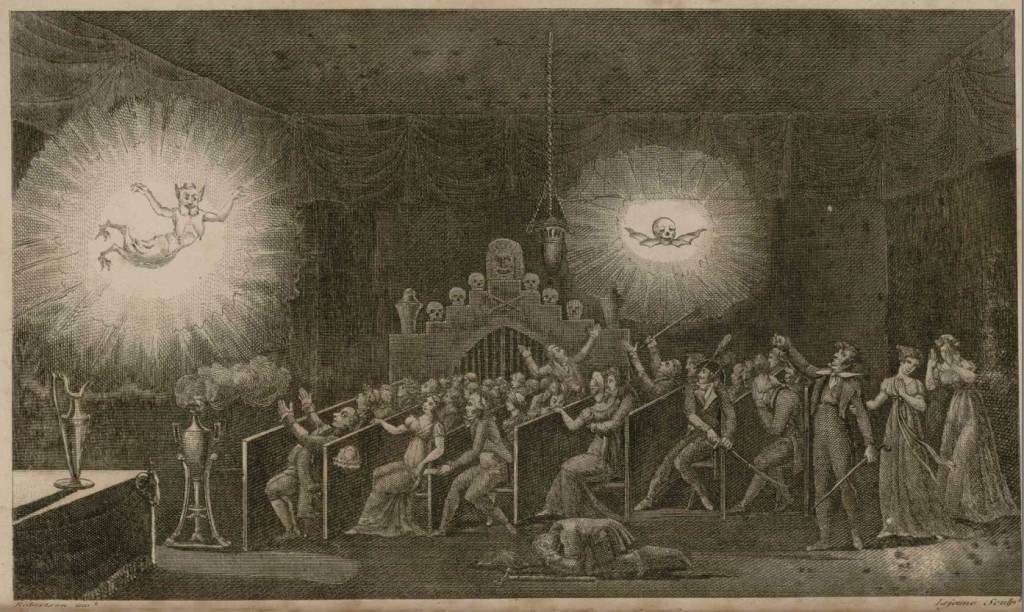

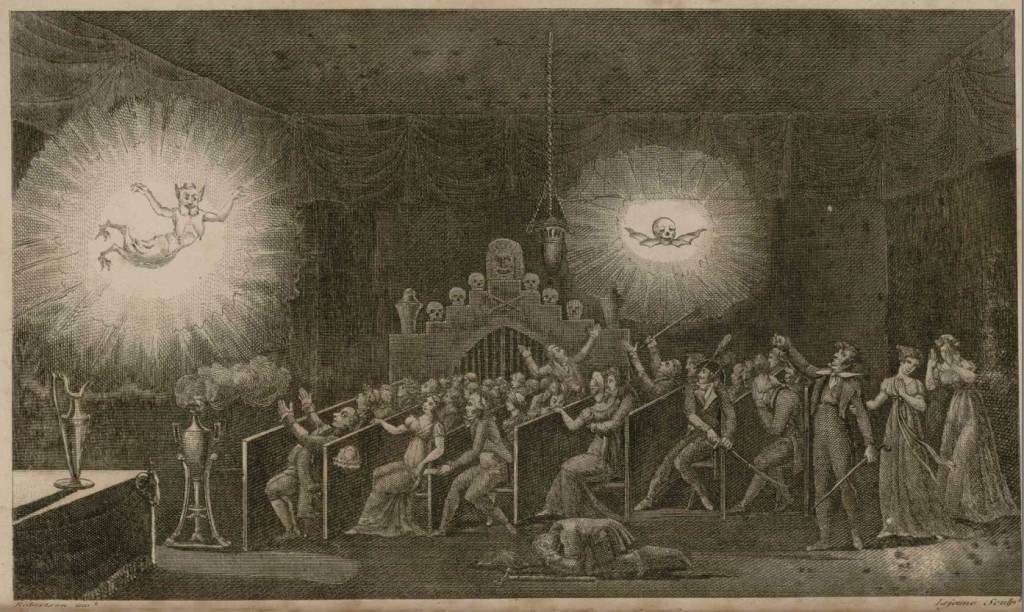

I have been doing quite a bit of research into Phantasmagorie for the Young Adult novel I’m writing about Josephine’s daughter Hortense.

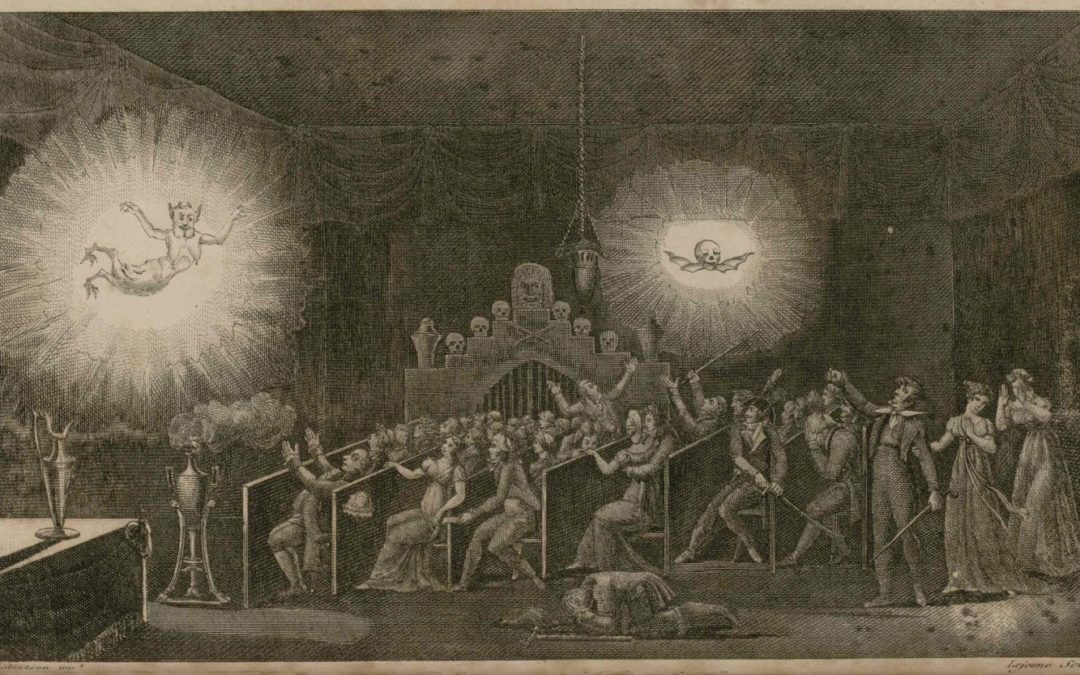

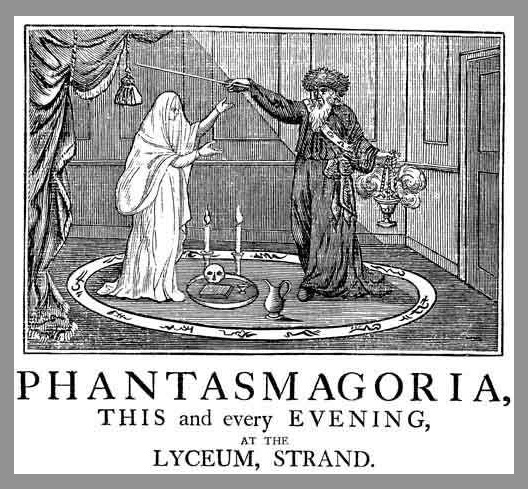

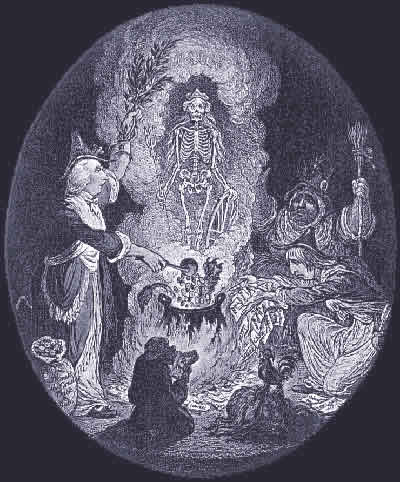

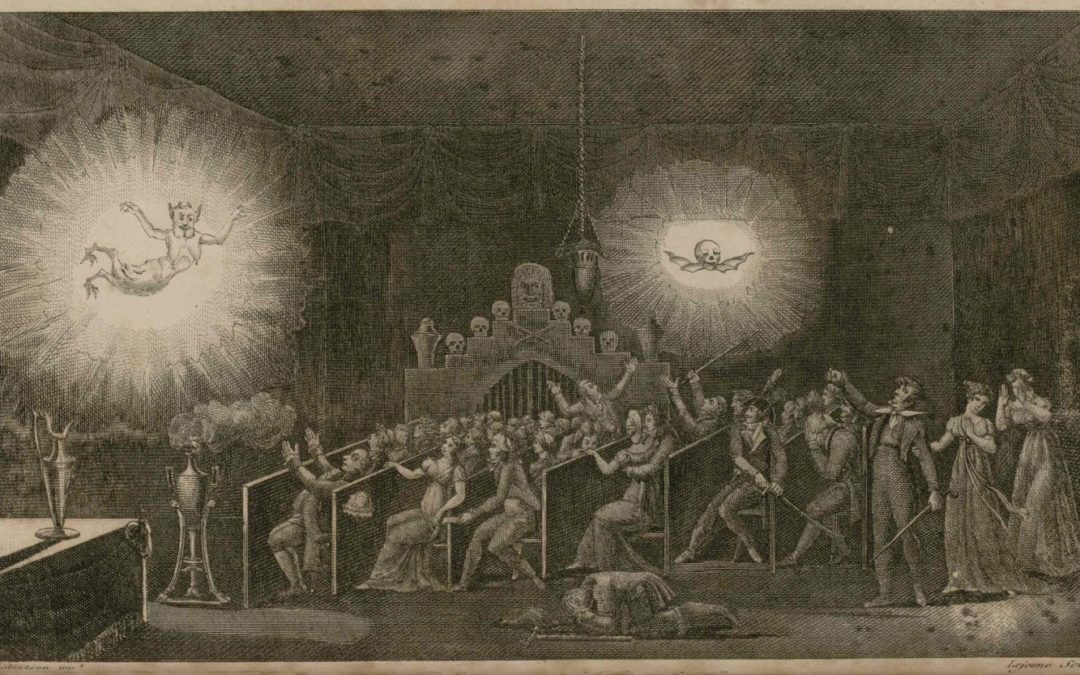

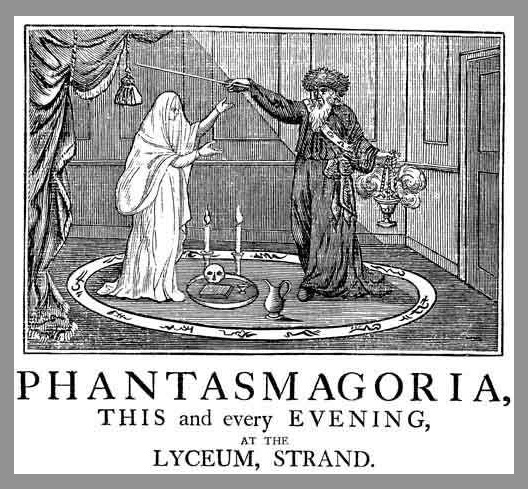

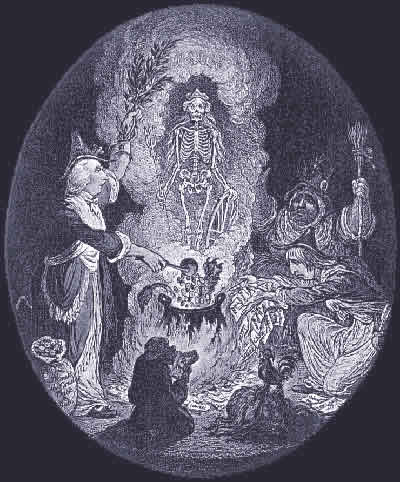

Phantasmagoria was an extremely popular “show” put on for both children and adults in France after the French Revolution, featuring the appearance of ghouls, ghosts, spectres and apparitions.

It was shown in other countries of Europe, but it was by far most popular in France, where so many had lost loved ones during the Terror, and where, apparently, a hunger for contact with the afterlife was strong.

Etienne-Gaspard Robertson (1763 – 1837) was the mastermind behind these productions. His first French exhibition of “Fantasmagorie” was at the Pavillon de l’Echiquier in Paris. He later staged it in the abandoned chapel of a Capuchin monastery near the Palace Vendome.

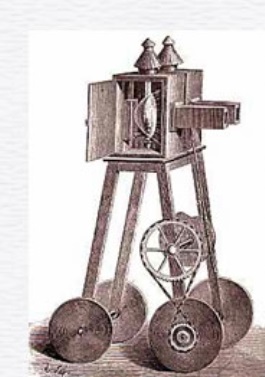

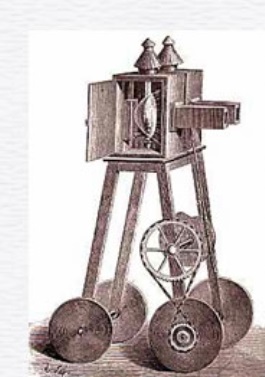

Robertson devised a double-lens lantern on wheels to create his ghostly effect, an invention which is considered the predecessor of the motion-picture camera. (In 1799 he got a patent for this camera, calling it a Fantoscope.)

To create the shadow play, Robertson used smoke, huge sheets of glass, mirrors, and several mobile lanterns. He would project from below the stage, and the hidden movement of a lantern created the illusion of motion. He would change the position of the lens to show a figure growing larger (and apparently closer), yet remaining in sharp focus. He also used rear projection, and projection onto gauze coated with wax, ironed to give a translucent appearance.

The purpose of the show was to terrify the audience—and it succeeded. It could well be considered the forefather of today’s horror movie.

Much of this information is from The History of the Discovery of Cinematography by Paul Burns, which unfortunately is not available on-line at this time.

For excellent documents, see The Richard Balzer Collection.

For a bibliography of books related to the history of cinematography, click this link.

For a full programme: Fantasmagorie de Robertson, Cour des Capucines, près la place Vendôme.

Robertson describes some of his phantasmagoria in his Mémoires.

(Phantasmagoria is not to be confused, by the way, with the 1995 interactive video game: Phantasmagoria!)

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Jan 5, 2017 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

The image above is Fireworks for the Entry of Louis XIII and Anne of Austria: The Lion, in “Reception de Louis XIII,” Lyons, 1623.

Happy New 2017!

I like the feel of this year already. I’ve weaned myself — to some extent — from toxic international news and immersed myself in finishing the eighth draft of Moonsick, my YA novel about Josephine’s daughter Hortense. (Yikes! Due this month.)

The funny side of revision

This is what revision sometimes feels like …

A New Yorker cartoon.

Newsletter coming

I’m also getting ready to send out a newsletter. Sign up here if you haven’t done so already. I will post links to it when it’s ready, but one advantage of signing up is that a subscriber wins one of my books with each newsletter.

A great audible edition of Middlemarch

When I’m not revising, or enjoying one of the many wonderful restaurants here in San Miguel de Allende with my husband, or puzzling over my latest watercolour, I’m listening to an absolutely outstanding audible edition of Middlemarch by George Eliot. This classic novel was destined to be forever on my Novels I’m Embarrassed to Admit I’ve Never Read List — in part because I just couldn’t cope with the pace and prose — but the narration by Juliet Stevenson really makes it come alive. Highly recommended!

Again, Happy New Year! You readers are the absolute best.

What audible recordings are your favourite? I’m always looking for recommendations.