by Sandra Gulland | Dec 17, 2018 | Mistress of the Sun, Recommended Books, Movies, Podcasts, etc., Resources for Book Clubs, Resources for Readers, The Shadow Queen, The Sun Court Duet |

The Baroque era in music generally spans 1600 to 1750. Mistress of the Sun and The Shadow Queen fall in what is called the “High Baroque” period (1650-1700), when French music rose to one of the peaks of its own unique expressive style.

Today, the best-known French Baroque composers are Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704) and Jean-Phillippe Rameau (1683-1764).

Jean-Baptiste Lully

Lully, a dancer and violinist born in Italy, became the court composer to Louis XIV in 1661, and a personal friend of the King. For over twenty years, he created the soundtrack underpinning all great occasions during the Sun King’s reign, including church music, operas, ballets, and much, much more.

YouTube has free excerpts of French Baroque music performed by ‘period’ ensembles, or groups that play using instruments and styles similar to those used at the time.

This excerpt of Lully’s brilliant opera Armide (1686), performed by Les Arts Florissants, directed by William Christie, gives an idea of the beautiful sounds of this period. This excellent group regularly plays and records French Baroque music. Also look out for Le Concert d’Astrée, directed by Emmanuelle Haim, and the work of Le Concert des Nations, directed by Jordi Savall, amongst many others.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Charpentier’s life was not so charmed. Labouring in Lully’s shadow, but arguably of equal talent, Charpentier never succeeded at getting an all-important court appointment but depended largely on the support of the powerful Jesuits. Even after Lully’s death in 1687, groups of Lully’s fans decried Charpentier’s work, insisting it was ‘too Italian’ to be truly French music. This hindered his success in his own lifetime, but his music is extraordinarily beautiful: you can listen to a live performance of a sonata for eight instruments here, played by the orchestra of Les Folies Françoises. Charpentier’s operas, like Médée, and oratorios, like David et Jonathas, are well worth seeking out on CD, but they’re best of all in live performance!

Jean-Phillippe Rameau

Where Lully was France’s greatest composer of the seventeenth century, Rameau was the giant of the eighteenth: he began his career as a celebrated music theorist and teacher and a composer of keyboard pieces, like the Pièces de clavecins (here played by Blandine Rannou).

Rameau only started writing opera at the age of 50, but they astonished the Parisian community, and immediately caused great conflict with the conservative fans of the sounds of Lully. He still met with great success, and collaborated with many fine authors, including Voltaire, to produce brilliant opera. ‘Tristes apprêts, pâles flambeaux’ is just one song from his opera Castor et Pollux; the video contains French and English subtitles, as well as glimpses of the musical manuscript and stills from the 2006 film “Marie Antoinette.”

You might also enjoy …

Although not necessarily a perfect historical or geographical fit, I enjoy the following YouTube links for background listening. (You might notice that they have a somewhat different sound from the examples above. Most of these are played on what we think of as modern instruments, whereas the examples above are played on “period” instruments, and are, therefore, closer to the original sound.)

The Best of Baroque: with renowned harpsichordist Ed Clark, violinist Brunilda Myftaraj and cellist Kathy Schiano.

Baroque Garden for Concentration — No. 7

Airs de Cour — French Court Music from the 17th Century.

From the “High Baroque” period in Venice:

Vivaldi’s Flute Concerto in D Major, RV429, played by the Accademia Montis Regalis.

Vivaldi’s Flute Concerto in G minor, ‘La Notte’, Op.10/2, played by Europa Galante.

‘Winter’ from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, played by the excellent Il Giardino Armonico.

Educational overviews:

For an educational overview, I recommend Best Baroque Music Composers, French Baroque (a lecture on “High Baroque” style plus recordings) and My favourite Baroque music.

A CD recommendation:

A beautiful CD, should you wish to purchase, is Chorégraphie, Music for Louis XIV’s dancing masters, by Andrew Lawrence-King.

Enjoy!

Most all of the knowledgeable information on this page is from Dr. Katie De La Matter, a scholar and performer of Baroque music. Thank you, Dr. Katie!

Information about the glorious image at the top can be found here.

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 31, 2018 | Questions Readers Ask, Resources for Book Clubs, Resources for Readers, The Shadow Queen, The Sun Court Duet |

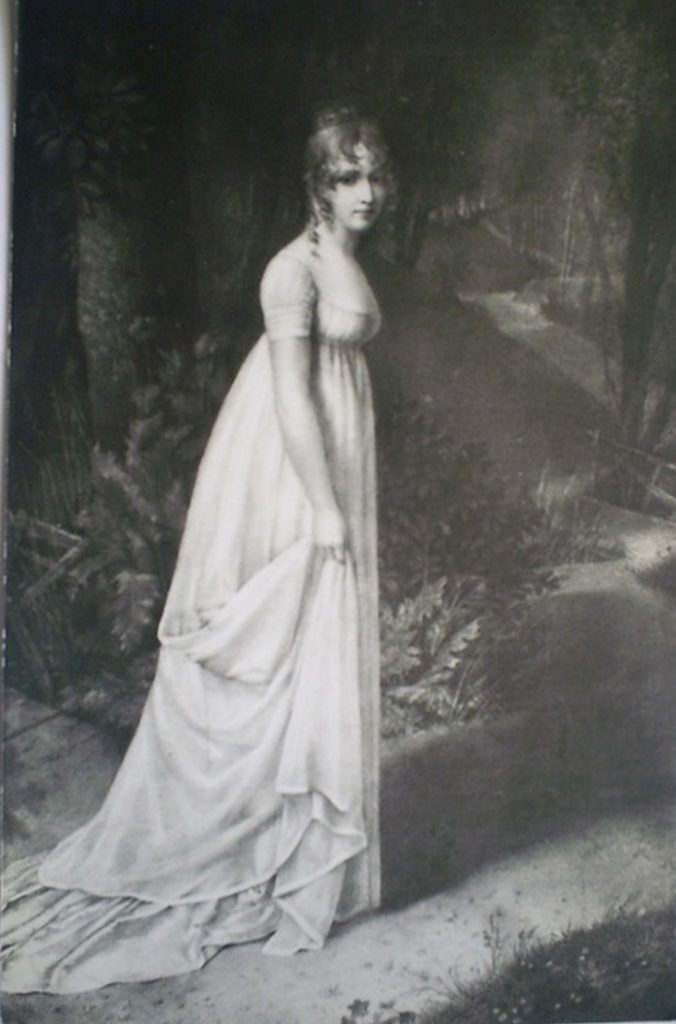

{Portrait of Claude des Oeillets}

The main character of my novel The Shadow Queen is Claude des Oeillets (dit Claudette), an impoverished young woman from the world of the theater. Socially scorned and denounced by the church, she lives on the fringes of society. As the daughter of a theatrical star, she exists in her mother’s shadow.

{Portraits of Madame de Montespan}

In contrast, Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan, lives at the heart of high society. She becomes Claudette’s obsessive passion, seeing in her a perfect life—a life without hunger and fear, a life of ease and beauty. Athénaïs’s life is everything Claudette’s is not.

While my other Sun Court novel, Mistress of the Sun, is set largely at Court, in both novels I am exploring the dynamic edge where court and ordinary life meet, with often explosive, unpredictable results. The Shadow Queen is about many things, but at its heart is the relationship between these two woman, Claudette and Athénaïs, who are close in age and share many of the same interests, yet are worlds apart. Claudette envies Athénaïs’s wealth; Athénaïs envies Claudette’s freedom, her life in the theater. Over time, they become dependent upon one-another. As Athénaïs’s devoted maid, Claudette is willing to do anything for her—up to a point.

It’s at that point that Claudette must step out of the shadows—and into the light of her own life.

Over the five years I was writing this novel, I considered many titles. In the end, I felt that the title The Shadow Queen metaphorically captured the spirit of this story on a number of levels.

As part of the theatrical world, Claudette lives in the shadows of society. When she joins Athénaïs at court, she becomes the shadow of the official “Shadow Queen.” The story is very much about the ever-fascinating Athénaïs, but it is also about Claudette’s “dark” obsession with her and what Athénaïs represents, an obsession that leads Claudette into the shadow-side of that opulent world, a world of corruption and black magic, the shadow-side of want and hunger.

Who, then, is queen of shadows? Officially, of course, it is Athénaïs, but it could be others as well—Madame Voisin, for example, a woman who fulfills dark wishes, and even our “Good Knight” Claudette.SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 30, 2018 | Publication, Questions Readers Ask, Resources for Book Clubs, Resources for Readers, The Shadow Queen |

A significant number of early reviewers of my new novel THE SHADOW QUEEN have expressed displeasure with the title; they feel it is misleading. They expected the novel to be the story of the Sun King’s official mistress, Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan, a position often referred to as “the shadow queen.” The title led readers to believe that they were going to get one story, when in fact they got another. I apologize if they feel that they were mislead.

These readers were responding to the Advance Readers’ Copies (“ARCs”) of the novel. The hardcover, with cover-flap copy, will make it clearer what, in fact, the story is about, and I hope that this will dispel some of the confusion.

Why that title?

But to address the concerns of some of my readers: Why have I titled this novel The Shadow Queen?

The main character of the novel is Claude des Oeillets (dit Claudette), an impoverished young woman from the world of the theatre. Socially scorned and denounced by the church, she lives on the fringes of society. As well, as the daughter of a theatrical star, she exists in her mother’s shadow.

In contrast, Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan, lives at the heart of high society. She becomes Claudette’s obsessive passion, seeing in her a perfect life, a life without hunger and fear, a life of ease and beauty. Everything Claudette’s life is not.

The novel is about many things, but at its core is the relationship between these two woman, Claudette and Athénaïs, who are close in age and share many of the same interests, yet are worlds apart. In the end, they become dependent upon one-another. Claudette, as Athénaïs’s devoted and even start-struck servant, is willing to do anything for her—up to a point.

And it’s at that point that Claudette must step out of the shadows—and into the light of her own life.

Over the five years I was writing this novel, I considered many, many titles. In the end, I was very happy with the title The Shadow Queen, a title enthusiastically embraced by a group of 50 writers, a number of whom had read the novel and felt that it was appropriate.

I am touched by the passionate concern of my readers, even when critical. Of course I have been both surprised and disquieted that some have objected. I personally feel that the title The Shadow Queen captures the spirit of this story on a number of levels. Claudette exists in the shadow of her mother, a drama queen. When she joins Athénäis at court, she becomes her shadow, the shadow of the official “Shadow Queen.” And, although the story is very much about the ever-fascinating Athénäis—as well as about Claudette’s obsession with her and all that she represents—it’s really a metaphorical title, more than a literal one.

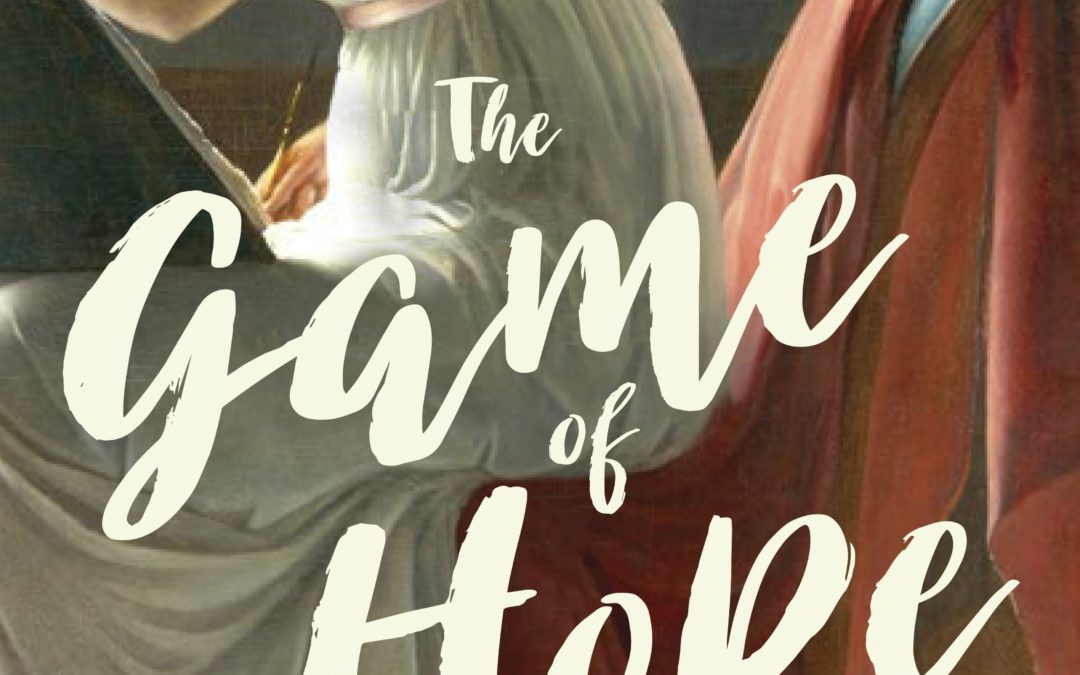

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 30, 2018 | Resources for Book Clubs, Resources for Readers, The Game of Hope, Young Adult Literature |

The painting on the cover of The Game of Hope is by French artist Marie-Denise Villers. It is popularly known as “Young Woman Drawing,” and can be seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The portrait is said to be of Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, but at least one art historian believes that it’s the artist’s self-portrait.

The painting was unsigned and for years it was attributed to the famous French artist Jaques Luis David. It wasn’t until 1995 that Villers was credited for the work.

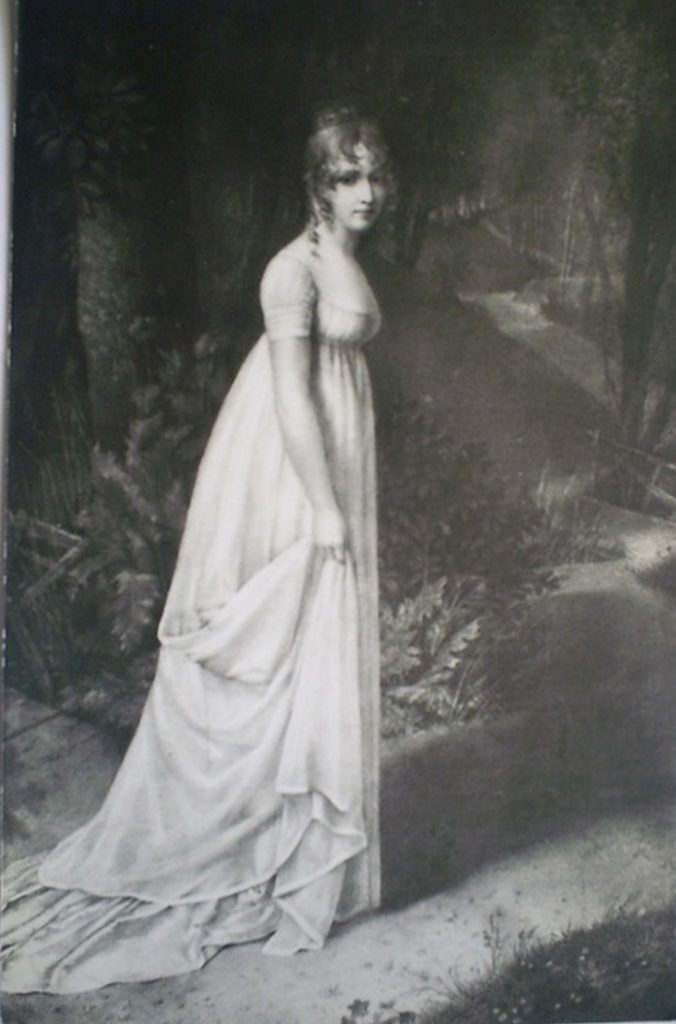

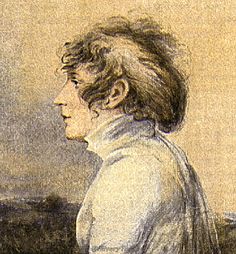

Although the painting is not a portrait of Hortense de Beauharnais, the young woman looks rather like her, I think, especially in spirit. Here is a portrait — possibly a self-portrait — of Hortense as a teen.

Hortense (possibly a self-portrait).

For portraits of Hortense at all ages, go to my Pinterest board.

For more on this intriguing painting, read “Prof. Anne Higonnet reveals a new twist in storied Metropolitan Museum of Art painting.” Higonnet’s slide presentation on this painting — “White Dress, Broken Glass” — can be seen online, although without the accompanying text it’s difficult to surmise her conclusion.

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 30, 2018 | Resources for Book Clubs, Resources for Readers, The Game of Hope |

Prisoner’s Base is a very old running game that was popular at Malmaison, and continues to be played today, although likely called by a different name. We don’t know which exact rules were played at Malmaison, but here is one version:

Divide an even-numbered group in half to make teams. As few as ten can play, but if the area is very large (i.e. a football field), as many as one hundred can participate.

With sticks or chalk or a line in the dirt, make a line between the two teams. About ten to fifteen paces in back of each team outline a square. These will be the “prisons.”

Each team picks one person to be held in the opposite team’s prison. This is usually someone who can run very fast and is why, in The Game of Hope, Eugène says that Hortense is always chosen.

Once the play begins, each team chooses someone to rescue their imprisoned team member and to bring him or her back without being “caught” (tagged, that is).

If that person makes it to the prison without being tagged, then the goal is to wait and chose a moment for both to try to run back to their team’s side without getting “recaptured.

If, however, the person does get caught, then he or she also becomes a prisoner in need of rescue.

At the end of a set time, the team with the most prisoners wins. An alternative rule is to play until one team has captured all the opposing team’s members.

For more information on Prisoner’s Base and other historical running games:

Children’s Games 1560 by Bruegel the Elder

by Sandra Gulland | Nov 30, 2015 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Resources for Book Clubs, The Josephine B. Trilogy |

The above image is a portrait of Josephine before she met Napoleon.

It is always hard for me to read biographies about Josephine. I’ve yet to read one I don’t have a quibble with. The same holds for a “Great Lives” BBC broadcast I listened to recently on Josephine. It pleases me that Josephine was chosen as one of the “Great Lives,” but there were a number of statements made that I very much question. One statement made was that she was very promiscuous. I ask you: How many lovers does a “very” promiscuous woman have?

How many lovers did Josephine have?

For Josephine, there was General Hoche, and—as is claimed — Director Barras, and — also claimed — Captain Charles.

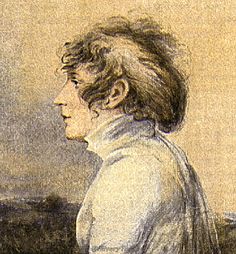

Portrait of General Hoche.

Although there is no absolute evidence regarding Josephine’s involvement with General Hoche, I personally believe that he might have been her lover. We really know nothing concrete, but Hoche was a lovable, attractive man, and she could very well have loved him.

Director Paul Barras

Regarding Director Barras, the question posed on the broadcast was, “What did she have to offer him?” The question was rhetorical: I.e. nothing, it was implied.

Au contraire. My historical consultant, Dr. Catinat, an authority on Josephine, told me that what Josephine had to offer were connections to wealthy Caribbean bankers, contacts she had made as a Freemason. (Women could be Freemasons then.) Barras, although powerful, was very much in need of financial aid, and Josephine was able to put him in contact with men who could help.

Josephine received money from Barras, no doubt, but Dr. Catinat felt that in balance, Barras was the one who came out ahead. This perspective is never mentioned. Instead, it is assumed that because Josephine was receiving money from Barras, she had to be sleeping with him.

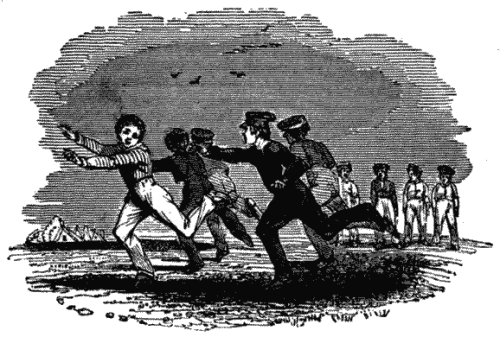

A UK political cartoon showing Josephine and her friend Therese dancing naked for Director Barras, Napoleon looking on.

Several mentions were made of the cartoon of Josephine and her friend Therese dancing naked for Barras, as if this was something that actually happened. They failed to note that the cartoonist was from the UK, which was at war with France. Enemies delight in portraying the enemy in a vile light. Again, while writing the Trilogy, I checked with my knowledgeable French consultants, who declared such stories untrue.

Was Director Barras heterosexual?

Dr. Catinat also told me that Barras was homosexual, possibly bisexual. He had no progeny — in spite of claims that he had many female lovers. I am personally inclined to think that he was more homosexual than bisexual, but there really is very little to go on.

Long ago someone told me that, in her opinion, Josephine was a woman who enjoyed the company of Gay men. Frankly, that rings true to me. Josephine was bohemian, and she loved men and women of the theatre and the arts.

And what about Captain Charles?

Which leads us to Josephine’s third so-called lover: Captain Charles.

Sweet Captain Charles, Josephine’s business partner.

Hippolyte Charles, too, had no progeny — that we know of — and although we know next to nothing about his personal life, in manner he was gay as a tea party. Supremely fashionable, he enjoyed dressing as a woman.

Furthermore, at the time when Josephine was supposedly having a torrid affair with the Captain, she was quite ill, suffering from fevers and violent headaches, likely brought on by a premature menopause (the result of her imprisonment during the Revolution).

The portrait of Josephine as a woman having a torrid love affair at this time is hard to fathom. I don’t know about you, but I simply cannot see Josephine in the bed of either of Director Barras or Captain Charles. And even if I could, would these three lovers make her worthy of the label “very promiscuous”? I think not.

The BBC broadcast mentioned that Josephine was mesmerizing to men. Yes, she certainly was. What they failed to mention is that she was well-beloved by women as well. As a rule of thumb — at least in my book of Observations of the Human Species — is that a promiscuous, manipulative, calculating woman is given a wide berth by other women. Josephine was trusted by women.

I rest my case.

(For more on this theme, see Josephine: Saint or Sinner? (Who knows?)

What have I been doing?

Other than spending quite a bit of time in Physio Therapy to help my Hip Bursitis (ouch!), I continue to wrestle with the Moonsick outline. It’s a big job, but I’m happy to report that it is coming along.

Great links to share…

The news continues to be dire. I am given hope by the resilience and creative joie d’vivre of the Belgians in their response to the order not to post telling photos to social media during the lock-down. National emergency? Belgians respond to terror raids with cats. This one is one of my favourites:

This YouTube video of people dancing on a Paris Metro is pure joy to watch.

I belong to a FaceBook group of authors, and now and then one of the members asks for help with coming up with a title. One of the authors posted a link to a Title Generator. It may never come up with a usable title, but it’s fun.

I started writing historical fiction because I wanted to imagine a world “peopled” by horses. I no longer have a horse of my own, and my riding days are behind me, but I continue to be captured by these beautiful creatures. This video on wild horses is stunning.

Have a great week!