by Sandra Gulland | Nov 28, 2008 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

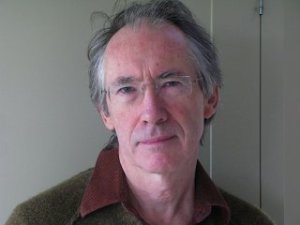

I’ve just finished reading Atonement by McEwan: what a masterful novel. I immediately searched the Net for discussions about it. It’s a novel that holds its grip. Now, what will I read? Everything seems pale by comparison.

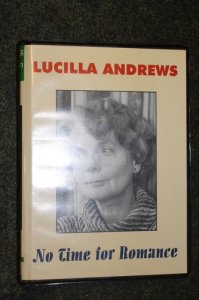

It is, technically, a historical novel. I recalled the plagiarism scandal: McEwan had apparently too-closely borrowed from a non-fiction account. Here, for example, is from Lucilla Andrews‘s 1977 memoir, No Time for Romance:

“Bit sort of tight. Could you loosen it?” … Then as I did not think it would do any damage to loosen the gauze bows, I let go of his hand, stood up, undid the first and, as the sterile towel beneath slid off and jerked aside the towel above, very nearly fainted on his bed. The right half of his face and some of his head was missing. I had consciously to fight down waves of nausea and swallow bile, wait until my hands stopped shaking and dry them on my back before I could retie the bow… [After he dies in her arms, a Sister says to her] “Go and wash that blood off your face and neck, at once, girl! It’ll upset the patients.”

And this from McEwan, in Atonement:

“These bandages are so tight. Will you loosen them for me a little?” She stood and peered down at his head. The gauze bows were tied for easy release … She was not intending to remove the gauze, but as she loosened it, the heavy sterile towel beneath it slid away, taking a part of the bloodied dressing with it. The side of Luc’s head was missing … She caught the towel before it slipped to the floor, and she held it while she waited for her nausea to pass … fixed the gauze and retied the bows … The Sister straightened Briony’s collar. “There’s a good girl. Now go and wash the blood from your face. We don’t want the other patients upset.”

I remember the outrage over this and other “borrowed” passages. McEwan is beyond brilliant, but I think he could have integrated his research more, made it his own. I did feel that the war sections, although overwhelmingly powerful, were just a bit too research-thick. He is at his strongest, I think, when his focus is tight, when his characters are face-to-face.

I’m not sure, frankly. I’m still under the spell of this amazing novel.

————

Now, two days later, I’m still puzzling over this novel; that’s a wonderful feeling, when characters take up residence. I like the puzzles it leaves. I long for people to talk to about it. It would be an excellent selection for a book club, because there is so much to discuss.

Insofar as the plagiarism accusations, I think there is a strong case to be made “for the defense.” Writers are by nature magpies, stealing shiny things to make their nest. We are sparked by ideas, and throw them into the stew-pot of the novel. Had that nurse and patient story been told to me by a friend, I would certainly have used it. I gather my materials everywhere I go.

So is it so very different when the inspirational story is in written form? It’s touchy. I do think one needs to be more careful. What I do: I break up an account into bits, use parts here and there. I make sure to put quoted sections in quotes in my notes, so that I know to reword it. Even so, the source underpinnings of a particular scene might be evident to someone who knows the material well.

The Life of Pi was inspired by another work of fiction. There is a scene in Geraldine Brook‘s prize-winning novel March I know I’ve read elsewhere—I just can’t recall where. Novelists are blessed to find accounts that give them the true-life detail they need, and are apt to consume such accounts hungrily.

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Jul 8, 2008 | Adventures of a Writing Life |

I’m at home (ahhhh) and unpacking, making lists—lists and lists and lists. First item: do not get overwhelmed!

I did fairly well with all that moving: I left behind four things.

One, my wireless mouse. Too bad, but at least it’s replaceable.

Two, my Body Shop face cleanser, which I learned I can travel without.

Three and four, books I was reading and very much enjoying. The first, Conceit by Mary Novik, has been generously resent to me compliments of the author. Thank you, Mary! It’s a story told from the point-of-view of John Donne‘s daughter, every sentence a joy, and I’m eager to dive back into it.

The other book lost was Ghostwalk by UK writer Rebecca Stott—another stunning historical novel—which I left on the airplane on the very last leg of this long journey. I’m upset by this loss! This book was signed to me by Rebecca, with whom I read in Kansas City—is not replaceable. So, I add to the top of the list: see if I can track it down.

And, also on the list: prepare to have my MacBook Pro replaced. Apple has seen the light.

by Sandra Gulland | May 20, 2008 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Recommended Books, Movies, Podcasts, etc. |

Penelope Fitzgerald‘s Offshore and The Blue Flower are on my list of all-time great novels, but what I love best about her is that she didn’t start writing until her late-50s.

To quote from the Guardian book blog, “The quiet genius of Penelope Fitzgerald”:

Fitzgerald was a wonderful writer, and since her death in 2000 her reputation has continued to soar. Despite a late start (she began writing her first novel when she was almost 60, composing it as a diversion for her dying husband), she gained immense popular and critical acclaim during the last 20 years of her life. She won the Booker (for Offshore), and became the first non-American to win the National Book Critics’ Circle award (for The Blue Flower, which many consider her masterpiece). In the eight years since her death, an increasing number of readers—including AS Byatt, Frank Kermode and Hermione Lee—have begun speaking of her as the greatest English novelist of recent decades.

I heard Penelope Fitzgerald interviewed by Eleanor Wachtel on the CBC radio show, Writers & Company. I was struck by her account: her first novel was a mystery. Accepted for publication, her editor asked her to cut it by half. She did so, and continued to do so for every book she wrote.

A good lesson, that.

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 25, 2008 | Baroque Explorations |

I really liked this blog post by Patricia Simoes on historical fiction: Fiction Versus History: Which is most truthful?

What turns me off from traditional historical writing is the distance from which the story is told. When I pick up a book on a historical figure, I want that book to take me into the head space and emotional state of the person I’m reading about. Unfortunately most history books are unable to do that. They are told from the view point of the observer or researcher. And despite the historian’s best efforts to give the protagonist a personality, it always seems to fall short of what the real person must’ve been.

My alternative to history books has become historical fiction. They provide the depth and complexity of character that I crave as a reader and the historical background that I appreciate learning about.

Discovering the past is my main motivation for writing historical fiction. Research sparks me, but it’s only through delving deeply into the day-to-day lives of my characters that I even begin to understand.

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 12, 2008 | Baroque Explorations |

It disturbs me that “fiction” is getting such a bad rap in the U.S. press, that publishers feel they can’t market a novel, but that a true story is okay, that readers hunger for “truth” and will pay for it.

Since when has memoir been held to documentary standards? Memoir is a story created from life. I write historical fiction, and in delving into the research, I’ve come to see quite clearly that historians write fiction, as well. The line between fact and fiction is fuzzy, always, and I don’t understand this urge to nail it down. Facts can be misleading, and fiction can be revealing.

Story is how we explain the past — our history — to ourselves. Story is a powerful tool, and it is story that sets us apart from the world of animals (at least insofar as we know!).

Yet I’m guilty myself, I know. I love that “wow” moment when reading historical texts, thinking: Imagine: this actually happened. I think the issue is not whether something is true or false, but the understanding, the contract that is created between the author and reader. The outrage is: “We have been misled.” Frey’s memoir was more fiction than fact, but was marketed as fact. Even so, I have trouble understanding the furor.

One of my first historical reveries was brought on by a diary I read of a Quaker young woman in 18th century England. I was swept away by this “true” account. On my next trip to London, I researched her life; it was there that I learned that the diary was fiction, a novel. I felt disillusioned, let down, but then thought: “What a good novel.” For it drew me into the world of the past in a very real way – and that’s what fiction can do that fact cannot.

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave