by Sandra Gulland | Nov 18, 2018 | Baroque Explorations, On Research, The Game of Hope, The Shadow Queen |

In preparing for a video presentation of The Shadow Queen to book clubs here in San Miguel de Allende, I’ve been revisiting the world of that novel — especially the magical world of 17th century theatre in Paris. Rereading this blog post, written long ago, I was captured once again by the story of Molière and his much younger wife Armande. Theirs was a story I was planning to write before I got spirited away into the world of The Game of Hope.

And so here, to share, is my post from 2009, spruced up with wonderful visuals. (Thank you, Internet!)

I’m doing a great deal of research right now into the theater world of 17th century France. My focus is on Claude de Vin des Oeillets, the daughter of actors, but along the way I’ve been encountering many wonderful characters. So many stories!

Molière’s wife Armande, 23 years his junior

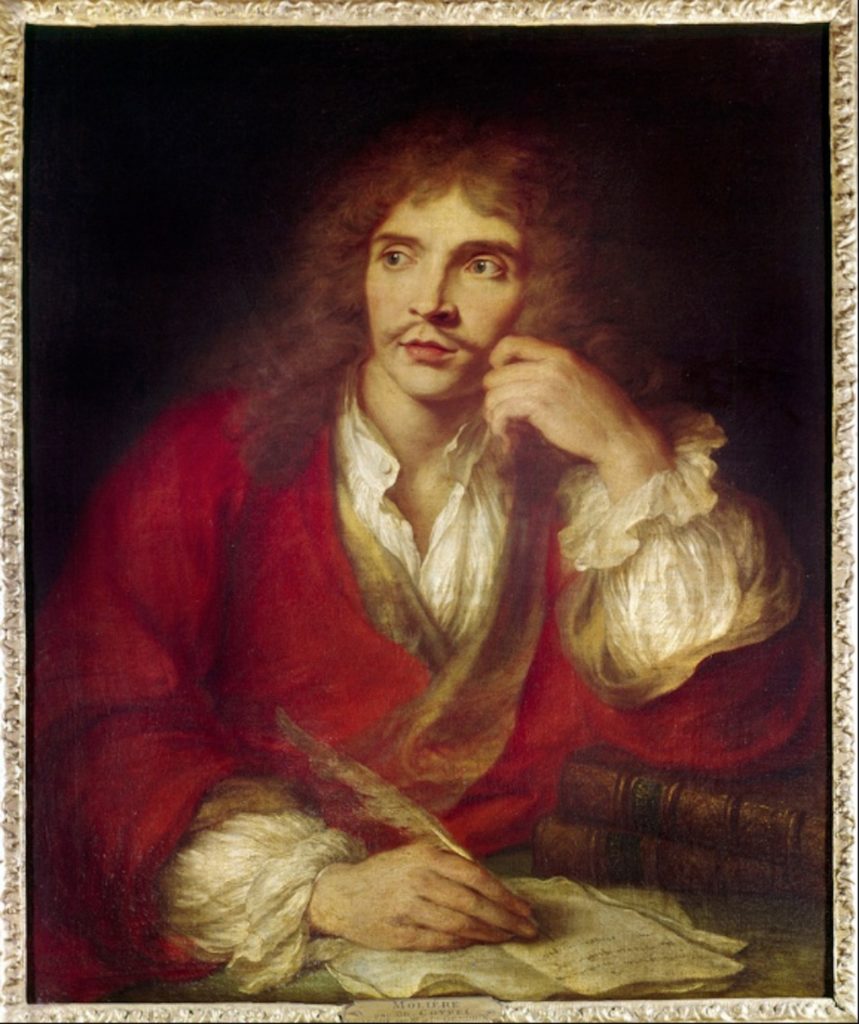

One, in particular, is that of the actress Armande Béjart, Molière‘s wife. He was 40 when they married, she only 17. She had known him all her life, and must have regarded him as something of a father and teacher. Indeed, he had taken charge of her education as a child.

They were a miserable couple. It is said that Armande was heartless and vain. She was considered a frivolous, giddy flirt, and was quite likely unfaithful (possibly to Lauzun, and possibly to the comte de Guiche); certainly Molière was consumed by jealousy. After the birth of a son, and then a daughter, they lived apart, yet they continued to work together closely on the stage. Molière could simply not stop doting on her . . . and neither could the public. She was a brilliant actress, and Molière was inspired to write many roles specifically for her.

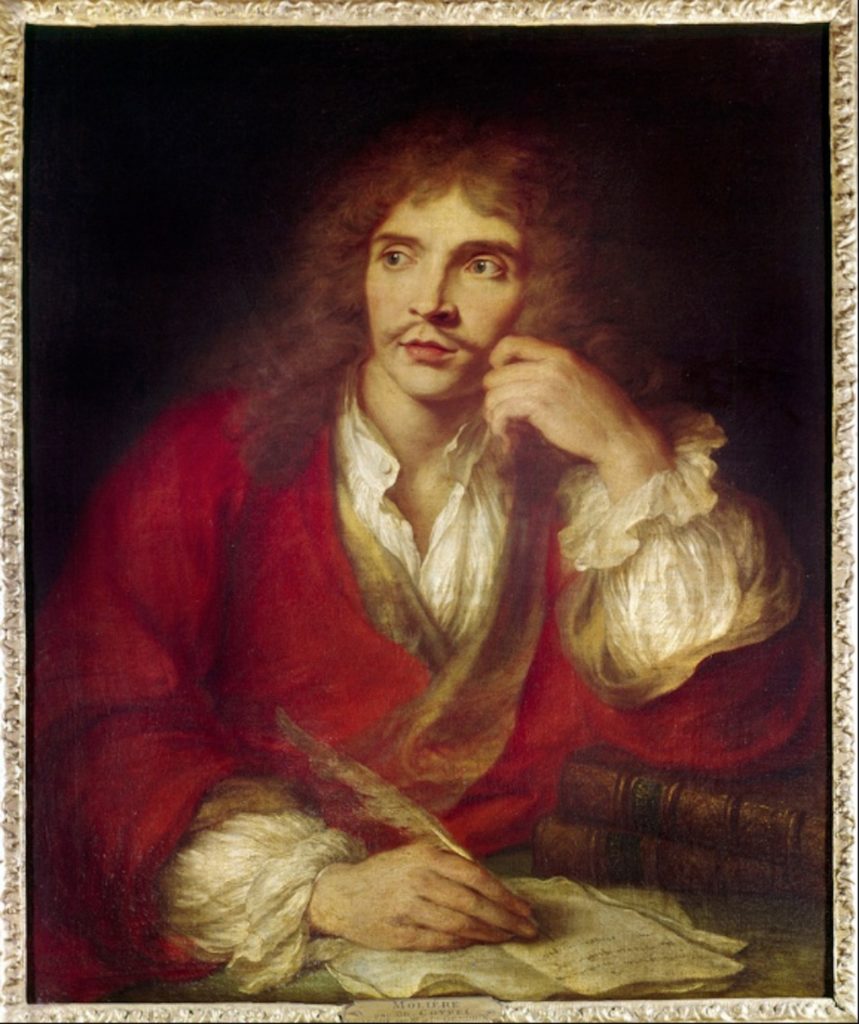

Molière

A mutual friend eventually persuaded Armande to reconcile with her increasingly consumptive and love-sick husband. She did, putting him on a strict meat diet, yet he continued to decline. On the day of the 4th performance of “The Imaginary Invalid,” in which he starred, Armande begged him not to play. He refused, knowing how many depended on the performance for their livelihood.

At the end of play, Molière (ironically playing the part of a hypochondriac) had a convulsion, which he tried to disguise with a harsh laugh. The curtain was hastily lowered and he was carried to his house. Always a comedian, he said on his deathbed: “I have set a detestable example. From now on, no playwright will be content until he has killed an actor.”

After her husband’s death, Armande proved to be anything but giddy and frivolous, fighting passionately for her husband’s right to be respectfully buried by the church (a fight she sadly lost), and then running Molière’s theatrical company with astonishing confidence and aplomb, making a number of difficult decisions that proved to be very successful. He would have been pleased.

I love her saucy attitude, but most of all I love how talented she was, and how capable she proved to be as a widow. Someday I hope to write about her.

[Note: This post was originally published on Hoydens and Firebrands, a website of women who write about the 17th century.]

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 31, 2018 | Questions Readers Ask, Resources for Book Clubs, Resources for Readers, The Shadow Queen, The Sun Court Duet |

{Portrait of Claude des Oeillets}

The main character of my novel The Shadow Queen is Claude des Oeillets (dit Claudette), an impoverished young woman from the world of the theater. Socially scorned and denounced by the church, she lives on the fringes of society. As the daughter of a theatrical star, she exists in her mother’s shadow.

{Portraits of Madame de Montespan}

In contrast, Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan, lives at the heart of high society. She becomes Claudette’s obsessive passion, seeing in her a perfect life—a life without hunger and fear, a life of ease and beauty. Athénaïs’s life is everything Claudette’s is not.

While my other Sun Court novel, Mistress of the Sun, is set largely at Court, in both novels I am exploring the dynamic edge where court and ordinary life meet, with often explosive, unpredictable results. The Shadow Queen is about many things, but at its heart is the relationship between these two woman, Claudette and Athénaïs, who are close in age and share many of the same interests, yet are worlds apart. Claudette envies Athénaïs’s wealth; Athénaïs envies Claudette’s freedom, her life in the theater. Over time, they become dependent upon one-another. As Athénaïs’s devoted maid, Claudette is willing to do anything for her—up to a point.

It’s at that point that Claudette must step out of the shadows—and into the light of her own life.

Over the five years I was writing this novel, I considered many titles. In the end, I felt that the title The Shadow Queen metaphorically captured the spirit of this story on a number of levels.

As part of the theatrical world, Claudette lives in the shadows of society. When she joins Athénaïs at court, she becomes the shadow of the official “Shadow Queen.” The story is very much about the ever-fascinating Athénaïs, but it is also about Claudette’s “dark” obsession with her and what Athénaïs represents, an obsession that leads Claudette into the shadow-side of that opulent world, a world of corruption and black magic, the shadow-side of want and hunger.

Who, then, is queen of shadows? Officially, of course, it is Athénaïs, but it could be others as well—Madame Voisin, for example, a woman who fulfills dark wishes, and even our “Good Knight” Claudette.SaveSave

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Mar 30, 2018 | Publication, Questions Readers Ask, Resources for Book Clubs, Resources for Readers, The Shadow Queen |

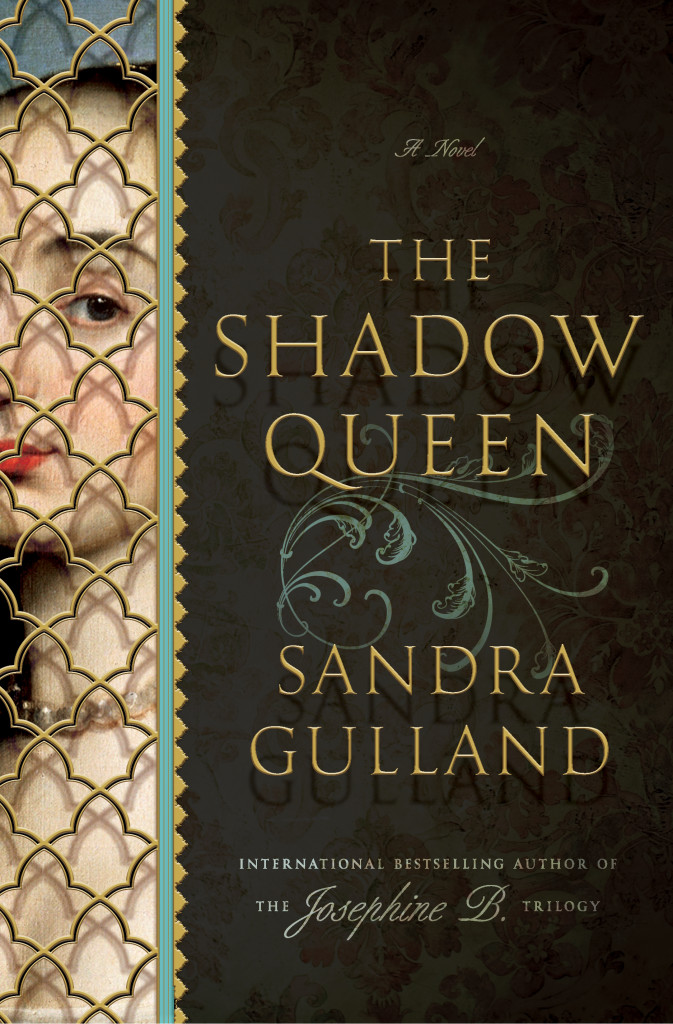

A significant number of early reviewers of my new novel THE SHADOW QUEEN have expressed displeasure with the title; they feel it is misleading. They expected the novel to be the story of the Sun King’s official mistress, Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan, a position often referred to as “the shadow queen.” The title led readers to believe that they were going to get one story, when in fact they got another. I apologize if they feel that they were mislead.

These readers were responding to the Advance Readers’ Copies (“ARCs”) of the novel. The hardcover, with cover-flap copy, will make it clearer what, in fact, the story is about, and I hope that this will dispel some of the confusion.

Why that title?

But to address the concerns of some of my readers: Why have I titled this novel The Shadow Queen?

The main character of the novel is Claude des Oeillets (dit Claudette), an impoverished young woman from the world of the theatre. Socially scorned and denounced by the church, she lives on the fringes of society. As well, as the daughter of a theatrical star, she exists in her mother’s shadow.

In contrast, Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan, lives at the heart of high society. She becomes Claudette’s obsessive passion, seeing in her a perfect life, a life without hunger and fear, a life of ease and beauty. Everything Claudette’s life is not.

The novel is about many things, but at its core is the relationship between these two woman, Claudette and Athénaïs, who are close in age and share many of the same interests, yet are worlds apart. In the end, they become dependent upon one-another. Claudette, as Athénaïs’s devoted and even start-struck servant, is willing to do anything for her—up to a point.

And it’s at that point that Claudette must step out of the shadows—and into the light of her own life.

Over the five years I was writing this novel, I considered many, many titles. In the end, I was very happy with the title The Shadow Queen, a title enthusiastically embraced by a group of 50 writers, a number of whom had read the novel and felt that it was appropriate.

I am touched by the passionate concern of my readers, even when critical. Of course I have been both surprised and disquieted that some have objected. I personally feel that the title The Shadow Queen captures the spirit of this story on a number of levels. Claudette exists in the shadow of her mother, a drama queen. When she joins Athénäis at court, she becomes her shadow, the shadow of the official “Shadow Queen.” And, although the story is very much about the ever-fascinating Athénäis—as well as about Claudette’s obsession with her and all that she represents—it’s really a metaphorical title, more than a literal one.

by Sandra Gulland | Apr 21, 2014 | Adventures of a Writing Life, On Research, The Shadow Queen, The Writing Process |

Given the recent revelations about French President François Hollande’s personal life, I think future writers of historical fiction are fortunate. They will have so many details to go on, from photos of President Hollande arriving for a rendezvous on a scooter to tweets sent by the former First Lady, his live-in mistress Valerie Trierweiler.

In writing biographical historical fiction that involves a public figure, it’s often difficult to discover how an intimate relationship evolves.

While writing my newest novel, THE SHADOW QUEEN, it was easy enough to see how lovers met, but a little more difficult to sort out how, exactly, a more intimate relationship came about—for these lovers were all “in the family,” so to speak:

Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan (Mistress 2) was the good friend of Louise de la Vallière (Mistress 1)—or so Louise thought.

Madame de Maintenon (Mistress 3) worked for Athénaïs (Mistress 2), as governess of her children by the King.

Claudette des Oeillets—heroine of THE SHADOW QUEEN who has a child by the King (rather a Mistress 3.5)—also worked for Athénaïs (Mistress 3) as her lady’s maid, and one has to presume that this arrangement was with Athénaïs’s approval.

The Hollande family tree, however, will be as difficult for future historical novelists to sort out as in days of old, and in this respect I don’t envy them in the least. Ms Ségolène Royal, Hollande’s former common-law wife, is the unmarried mother of his four children. Ms Trierweiler, his second partner, has three children by her second husband. That’s a family-menage of seven children—way too many to manage in a scene.

Film actress Julie Gayet, the newest Other Woman, has two children by her first husband, but it’s up for grabs whether or not she will be moving into the Élysée Palace, the official residence of the President of the French Republic. If she does, the international Press, you can be sure, will be watching.

There is a general perception that it is not uncommon for French leaders to have a mistress. Is this, however, fair? In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, having a mistress was almost a requirement for a French, English, Spanish or German king. Understandably, in my view, given that royalty had to marry for political reasons, not love.

Louis XIV, the Sun King, was a rather monogamous adulterer: he usually had only one mistress at a time. His cousin Charles II of England, however, had several mistresses at once. (The most famous was actress Nell Gwynn, who is reported to have once sabotaged a rival by putting laxatives in her food before her rendezvous with the King.)

In modern history, Edward VIII abdicated in 1936 in order to be with his mistress, the divorcee Wallis Simpson. Prince Charles married his long-term mistress Camilla Parker Bowles. And then, of course, we have President Clinton and Monica Lewinsky.

In one respect, I venture to say that the French do take the cake. A number of French shadow queens were significantly powerful women.

Gabrielle d’Estrees, the Catholic mistress of Protestant Henri IV, helped end France’s religious wars.

King Henri II’s mistress, Diane de Poitiers, imposed taxes, appointed ministers and made laws.

And, lest you think that the role of shadow queen is strictly sexual, consider Madame de Pompadour, who was King Louis XV’s mistress for almost two decades, despite—I’ve read—being unable to have intercourse. Instead, she provided the King with young women to sleep with.

I admire the French public for considering it none of the press’s business what their leaders do in their personal life … which makes me feel just a little trashy for even mentioning it all here. But then, I’m just thinking ahead, academically speaking. ;-)

Have you ever noticed how the word “courtesan” has the word “court” in it? From Wikipedia:

“In Renaissance usage, the Italian word cortigiana, feminine of cortigiano (“courtier”) came to refer to “the ruler’s mistress”, and then to a well-educated and independent woman of loose morals, essentially a trained artisan of dance and singing, especially one associated with wealthy, powerful, or upper-class men who provided luxuries and status in exchange for companionship.”

SaveSave

by Sandra Gulland | Aug 18, 2013 | Adventures of a Writing Life, Publication, The Shadow Queen |

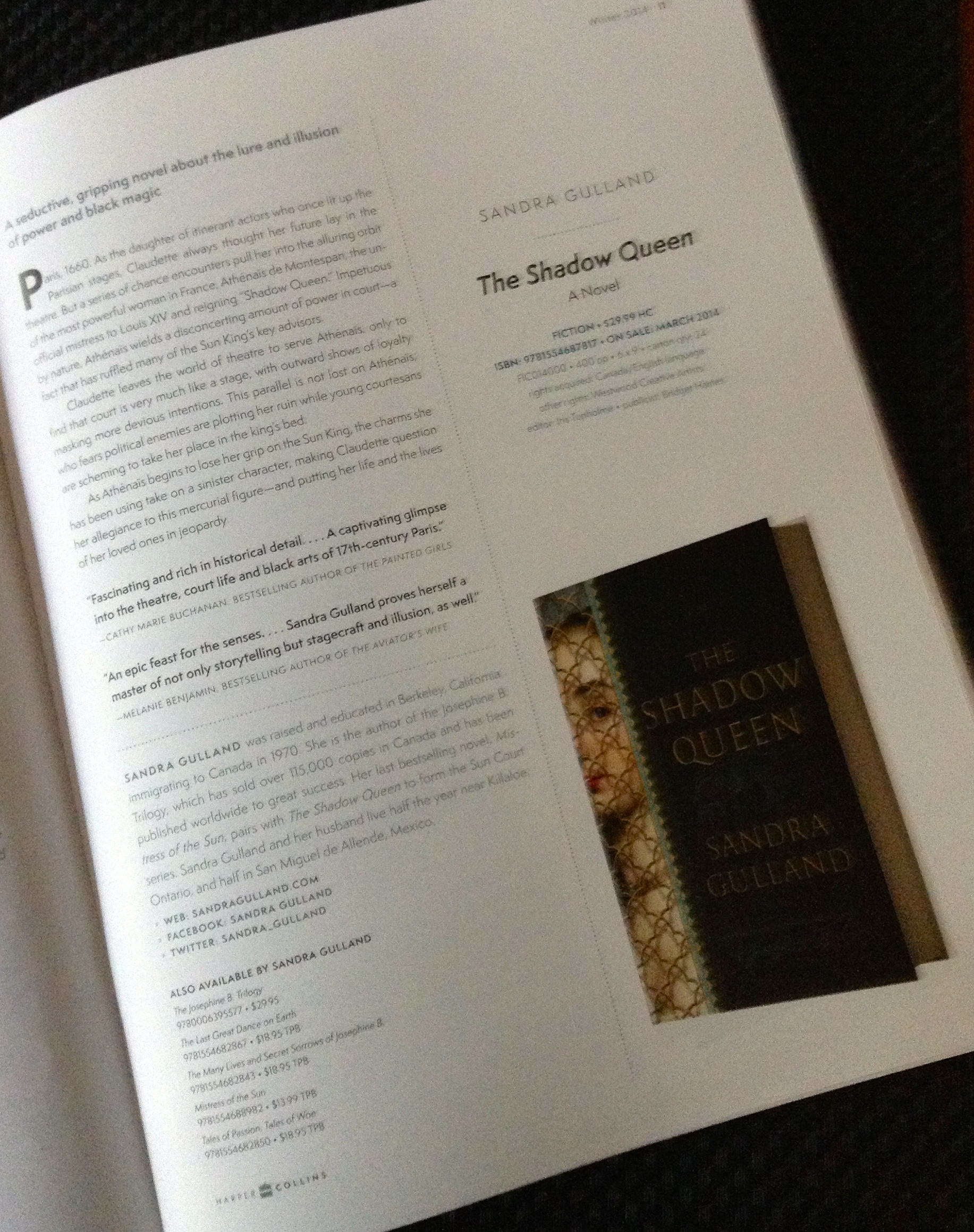

The HarperCollins Canada 2014 catalogue!

The main reason for this post is to share a great blog post on writing and publishing.

“25 steps to being a traditionally published author: Lazy Bastard Edition”—a post by Delilah S. Dawson—is an excellent overview of the writing and publishing process, as good an overview as I’ve ever read. I just sent the link to four friends who are working on novels. (Heh. By mistake I typed “wording” on novels.)

To give you the funny-but-hard-hitting sense of it, Step #1 is: If you’re actually lazy, GTFO.

Amen.

On the home front:

THE SHADOW QUEEN has a pub. date: April 8, 2014. I’ve sent off the corrected 1st Pass pages and I’ve only the Acknowledgements and the very last sentences of the novel to tweak. I’ve a storage box on my office floor where everything to do with The Shadow goes now, labelled “archival.” (I.e. my crowded basement.)

No more surprises, right?

Wrong! Yesterday evening, I got this Tweet:

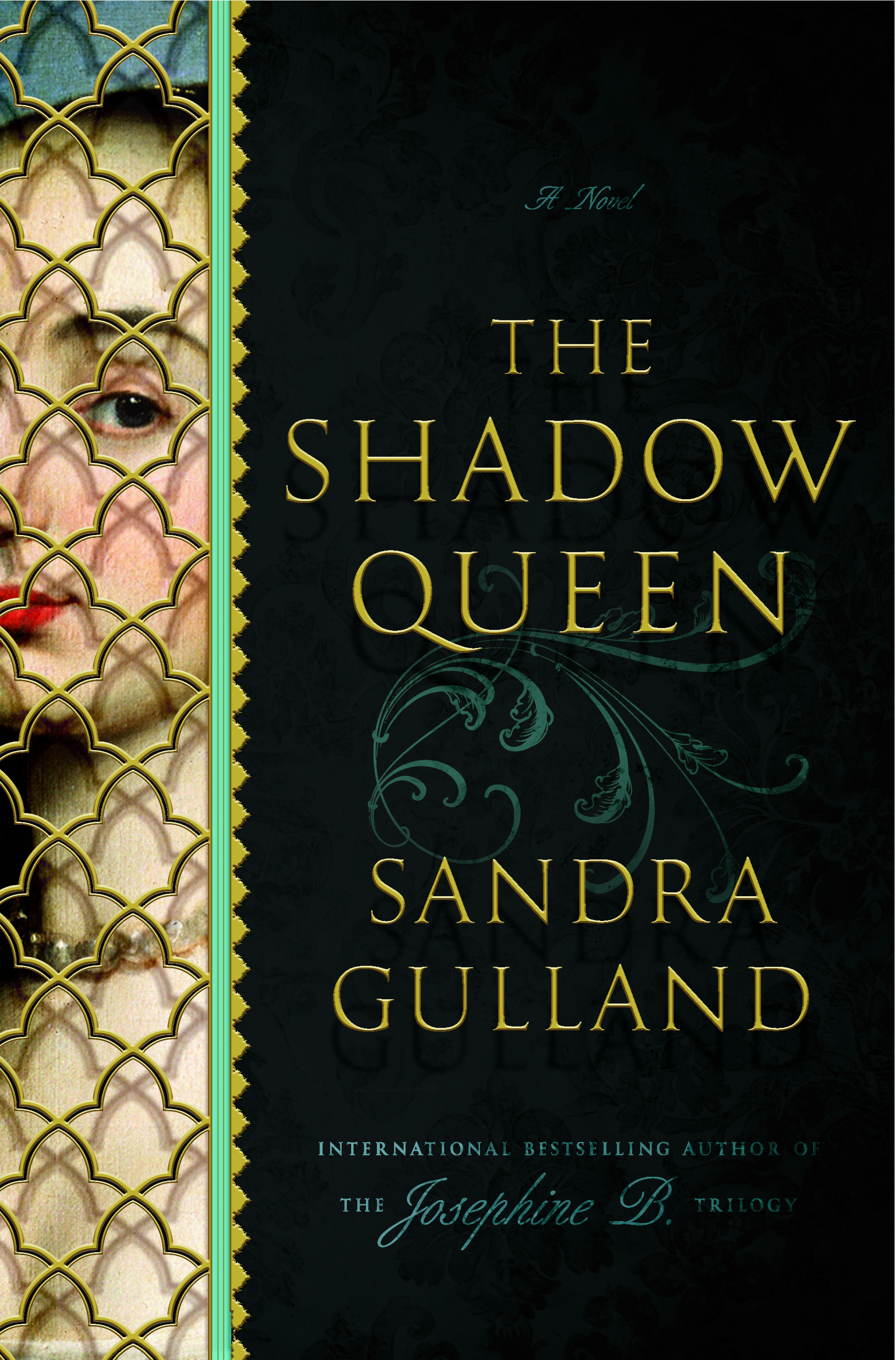

I was speechless! A portrait of my Claude? I didn’t think one existed. (I Googled for it when I began my research and came up with nothing.)

Look familiar?

I’ve emailed Doubleday to find out if they used the portrait as a basis for the cover.

I was pleased when I first saw the cover because the woman looked like how I’d imagined Claude to look. (Eyebrows!)

And now: well! To find out that it looks like the real Claude: I’m blown away.

Late breaking news (two days later): my editor at Doubleday, Melissa Danaczko, checked: the cover designer had never seen a portrait of Claude, much less this one.

Is that spooky-amazing or what?!